Microfilm and Digital Research

Intro:

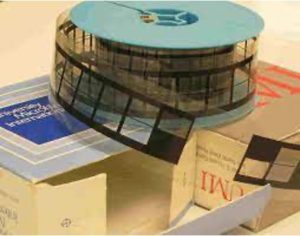

The History, Philosophy, and Newspaper Library holds over 100,000 reels of microfilmed newspapers in its collection as well as most of the University Library microfilm. The term “microform” encompasses microfilm and microfiche (as well as the now obsolete microcard.) What is microfilm and why do researchers and historians use it?

(University of Illinois Libguide to Microform)

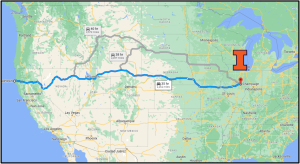

HPNL Microfilm at a Glance

1 reel of microfilm = 125ft

125ft * 100,000 reels = 2,367 miles

That’s the distance from UIUC to the Pacific Ocean.

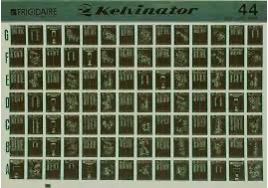

1 reel of microfilm = 13 days of New York Times

A Brief History of Microfilm

Microfilming technology began in the nineteenth century. John Benjamin Dancer an optician and instrument maker is credited with creating the first microphotograph and the microfilming process in 1839. Rene Dragon, a French optician, received the first patent for microfilm in 1859. He later worked with the French government during the Franco-Prussian War 1870-71 using carrier pigeons to transport microfilmed messages out of besieged Paris. The normal channels of communication had been interrupted by the war, including the post and telegraph. Previously carrier pigeons carried small handwritten messages, with microformatting technology they could send more messages with less space. By the war’s end, Dragon and Co had handled over 150,000 messages and a million private letters and dispatches.

Microfilm and formatting technology was taken up by newspapers in the 1930s, the New York Times began publishing microfilmed versions in 1935.

For more on the history of microfilm see UCLA’s Southern Regional Library facility’s great online exhibit on the history of microfilm

What kind of materials are available on microform?

- Illinois Historical Newspapers: Illinois Newspaper Directory (Many at HPNL–not all)

- Eighteenth Century French Fiction. Microfilm of 18th-century French books in the Library of Congress, Newberry Library, Bibliothèque nationale, and other libraries. (FILM X840.8 Ei44, RBML)

- American Women’s Diaries (Western Women). (FILM 305.40978 Am35, HPNL)

- Underground Press Collection 1963-1985 (FILM 071.3 Un3)

- Periodicals by and about American Indians 1923-1981 (FILM 973.049705 P418)

- Early English Newspapers (FILM 072 EA76)

- Newspapers from the Russian Revolutionary Era (FILM 057.1 NE)

- And many many more https://www.library.illinois.edu/hpnl/newspapers/index.php

Why Use Microfilm and Further Reading Suggestions

1. Newspapers are not made to last–so they need to be preserved. However, not all newspapers have been digitized.

- Although many newspapers have been digitized not all have been. As Ian Milligan examines in “Illusionary order: Online databases, optical character recognition, and Canadian history, 1997-2010” databases skew research. In 1998 there were 68 dissertations on Canadian History and the Toronto Star was cited 74 times. In 2010 with 69 dissertations the Toronto Star was cited 753 times. (pg 541-542) Milligan found a similar increase in citations in other digitized newspapers, but found that usage for non-digitized newspapers remained stagnant or even decreased.

2. Context and keywords

- Microfilm shows a whole page of a newspaper whereas many databases only show the article. Understanding the surrounding context may be lost in the process of history research. In “Newspapers and the Persisting Usefulness of Microfilm: A Matter of Context,” Joel Roberts gives an example in his dissertation–being forced to use microfilm by lack of digitized newspapers and being better able to trace the path of his subject, a jazz musician Bob Miller. By using microfilm Richards was able to theorize why Miller stopped making riverboat appearances in 1925–by reading the local news Roberts learned about a riverboat disaster at the time, and an increase in riverboats being advertised as “unsinkable.” He also was able to understand the origins of one of Miller’s songs the “Skeeter Scoot” which was a mosquito repellant brand that no longer exists but was advertised in microfilmed newspapers. (Roberts 25) It is likely he would not have been able to find such information through keyword searching articles about Bob Miller.

3. How we search and find.

- In thinking about digital sources vs microfilm it’s also worth thinking about what is lost and what is gained in text search ability and ease of research. Lara Putnam breaks down what is lost and what is gained by ease of access to digital resources in “The Transnational and the Text-Searchable: Digitized Sources and the Shadows They Cast.” It is a different process to use keyword searching as one’s primary means of doing research than to look through each page of microfilm to find information and well worth examining how changes in the research process effects one’s research.

4. Problems around microfilm

- Microfilm is far from perfect. As mentioned it is slow to use and harder to access. There is also content from localized editions of newspapers lost in the move from print newspaper to microfilm as Richard Saunders examines in “Too Late Now: Libraries* Intertwined Challenges of Newspaper Morgues, Microfilm, and Digitization.”

Further Reading

https://www.srlf.ucla.edu/exhibit/html/

https://guides.library.illinois.edu/microform

Milligan, Ian. 2013. “Illusionary Order: Online Databases, Optical Character Recognition, and Canadian History, 1997-2010.” Canadian Historical Review 94 (4): 540–69. doi:10.3138/chr.694.

Putnam, Lara. 2016. “The Transnational and the Text-Searchable: Digitized Sources and the Shadows They Cast.” The American Historical Review 121 (2): 377–402. doi:10.2307/43955768.

Saunders, Richard L. “Too Late Now: Libraries’ Intertwined Challenges of Newspaper Morgues, Microfilm, and Digitization.” RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, & Cultural Heritage 16, no. 2 (Fall 2015): 127–40. doi:10.5860/rbm.16.2.448.

Roberts, J. (2021). Newspapers and the Persisting Usefulness of Microfilm: A Matter of Context. Music Reference Services Quarterly https://doi.org/10.1080/10588167.2021.1991165

Saunders, Richard L. “Too Late Now: Libraries’ Intertwined Challenges of Newspaper Morgues, Microfilm, and Digitization.” RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, & Cultural Heritage 16, no. 2 (Fall 2015): 127–40. doi:10.5860/rbm.16.2.448.