From Emilee Mathews–

I have already mentioned elsewhere that I went to Japan last fall as part of a trip organized by the Art Libraries Society of North America. We were a total of 16 U.S. art librarians and participated in site visits and tours across a number of notable Japanese art libraries and museums.

I want to spent some time on the presentation I gave at the Tokyo National Research Institute for Cultural Properties (Tobunken), which involved exploring connections between University of Illinois and Japan / イリノイ大学 と日本 (Irinois Daigaku to Nihon). The least known person I spoke about was 滋賀重列 SHIGA Shigetsura, and so I want to take an opportunity to put out the new information I was able to synthesize from a couple sources.

I first learned about Shiga-san when I asked the University Archives for early material about Japan at the University, and they pointed me to this excellent post by former employee Salvatore De Sando. I was able to use this article as a jumping

off point to track down more information and follow up some leads, which I want to capture here in this post. I also want to capture my delight at being able to visit Shiga-san’s last remaining building he designed in Tokyo! More about that below.

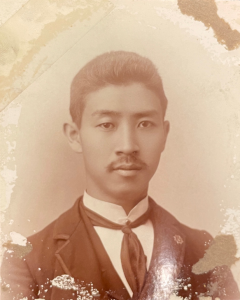

Japanese students began to matriculate into the University within a few years of the school’s founding, there are several we know about as documented in The Daily Illini. The first Japanese student who not only attended but also graduated from University of Illinois is Shiga Shigetsura in 1893 (pictured left), who also earned his degrees in architecture!

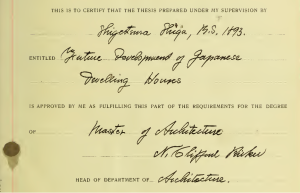

Shiga-san’s undergraduate thesis was on the effect of oil upon lime mortar, and his master’s thesis from 1905 is, Future Development of Japanese Dwelling Houses. You can see it is approved by none other than Nathan Clifford Ricker (pictured right), one of our most notable

alumni, who graduated in 1867 and was the very first student to graduate from an American architecture program. Ricker went on to become a professor in the architecture program, and later was the department head and dean of the college of Engineering (which Architecture was a part of at the time). We here at Ricker Library are always interested to see what our namesake got up to in his lifetime, and how he connects with other figures in the University of Illinois’ early history.

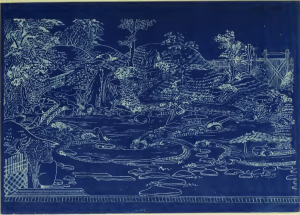

In his master’s thesis Shiga-san postulated that in the contemporaneous period of

Western influence and increased trade, Japan had the opportunity as a nation to rethink a core yet under-considered aspect of its building typology: that of domestic architecture. He had several recommendations for strategically introducing Western-influenced building programs, materials, and techniques into Japanese housing. As he is writing for an American audience, he discusses and illustrates the fundamental characteristics of Japanese dwellings, and typical Japanese gardens and temples.

Shiga-san made an impact both on campus and for the University of Illinois’ broader reputation, which the Illini Everywhere article documents quite well. He was elected vice president of the Architectural Club in 1892. He wrote articles in campus publications about his journey from Japan to California,

Japanese temples, Japanese women, and the history of exchange between Japan and Europe.

He also worked with the burgeoning Illinois Natural History Survey whose mission was, and still is, to conduct a scientific study of local ecology, and spent several summers traveling around Illinois collecting insect specimens.

I wanted to see for myself some of the insects Shiga-san collected, so I visited the Natural Resources Building and collection on campus (only two buildings south from Ricker in the Architecture Building!). I met Dr. Tommy McElrath who is an entomologist and is in charge of the INHS Insect Collection, which numbers in the millions. He told me that Shiga-san collected over 1,400 specimens for the insect collection.

I was surprised to hear that insects collected 130 years ago are still very much used today. I learned there are several reasons why historical specimens are useful and important. For example, at the time of my visit, several of Shiga-san’s collected insects were out on loan for a research project to compare insect body size over time to determine the impact of climate change. Two, the specimens were collected before industrial agricultural practices became commonplace in the state. For example, another specimen, the 9-Spot Lady Beetle, was plentiful at the time of collection but is currently extirpated in the state and on the federal endangered species list. Last, insect identification and classification is very much still ongoing. For example in just beetles alone, there are over 400,000 identified species, and the entomological community currently estimates there are approximately 15 million beetle species in the world. Two of the beetles we looked at from Shiga-san were consulted as part of a genus revision, one in the 1960s and one in 2015. (Thank you Dr. McElrath for explaining the significance to me, a non-science person.)

Shiga-san worked for the Natural History Survey in 1891 and 1892, and these specimens were collected to show at the Columbian Exposition which took place in 1893 in Chicago, Illinois. We see here (pictured right) from the Illinois building at the fair in which the University, only 25 years old at the time, showed visitors examples of collections and student work. Apologies for the very dark image, photography was only about a 30-year-old technology at the time.

The Columbian Exposition was also remarkable from a U.S.-Japan relationship perspective. While there had been other world’s fairs such as in London 1851, Philadelphia in 1876, Paris in 1889?, this 1893 was the first time that Japan as a nation decided to build their own pavilion. This was a building modeled after the Hooden or Phoenix temple in Kyoto, built by master workers, and was the largest of any country’s pavilions at the exposition. (Not incidentally, this was the first time Frank Lloyd Wright saw Japanese architecture and you could definitely say this was life changing for him and his body of work.) Shiga-san was connected to the exposition in 3 ways: first, as I mentioned, he spent several trips in regions across Illinois collecting insect specimens to be included in the exposition, in the Illinois building specifically for the state laboratory of Natural History. Second, he was actually employed as a clerk in the Japanese display (which is different from the pavilion) located in the Manufactures and Liberal Arts building, which a variety of countries showed examples of their specializations. Thirdly, he helped to secure Japanese art to be bought locally by Professor Frank Forrest Frederick who was one of two art professors at Illinois, which we have a newspaper article from the campus paper. We have evidence by way of a newspaper article in the campus daily news that art from the Japanese exhibition was on view for a week at the University.

Shiga-san graduated in 1893 and returned to Japan. He became a professor of architecture at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, now called Tokyo Tech. He also designed a building for Tokyo Tech. I’m hoping to find more information about that topic someday, perhaps a future trip to Japan!

He was the Architect to the Education Department of the Imperial Government, 1900-1903 and 1908-1912. He was awarded the Fifth Order of the Sacred Treasure; according to one source I have he was Second grade of Fourth rank in the Imperial Court, another says “bearer of the first grade rank of the imperial government.” Also, I see he was editor for a “Journal of Architecture” in the 1910’s. I would love to be able to add copies to Ricker’s collections someday.

Shiga-san looked back fondly on his time at Illinois, as he served as the President of the Japan alumni club for several decades and hosted Illinois visitors, including the Illinois Baseball team in 1928.

As I mentioned, I gave a presentation about Shiga-san to Japanese colleagues in October, 2024 in Tokyo while visiting. One colleague, KIKKAWA Hideki, was kind enough to point out to me that Shiga-san’s last known extant building he designed was recently added to the national historic register. As I had some free time I went ahead and visited the property, which is located near Iogi station in west Tokyo. It was a cute, very residential neighborhood with local schoolchildren planting a garden nearby. I was touched that Shiga-san’s master’s thesis was about domestic architecture, and his legacy is his family home he designed, which his family still lives in today. How wonderful is that!

Acknowledgments:

I’d like to acknowledge a number of people who helped me track down information on these topics: Sammi Merritt, Jameatris Rimkus, Bethany Anderson, Salvatore De Sando, Steve Witt, Tommy McElrath, and KIKKAWA Hideki.

Further Reading

There are several articles by and/or about Shiga-san in the Illini Everywhere article – I will just add below those that I consulted most heavily and/or were not covered in that article.

“CLUB HEARS TALK ABOUT JAPANESE TRIP.” Daily Illini, 23 October 1928.

“DISTINGUISHED JAPANESE GRADUATE OF THE STATE UNIVERSITY.” Daily Illini, 19 January 1900.

“旧滋賀家住宅主屋/Former Shiga Family Residence Main Building.” Suginamigaku, March, 2024.

JAPANESE ILLINOIS CLUB INVITATION TO TOURING ILLINI. Daily Illini, 21 April 1915.

Shiga, Shigetsura.Future development of Japanese dwelling houses. Master’s Thesis, 1905.