Censorship is the act of preventing or obstructing another’s ability to express their thoughts through media, actions, and speech. American citizens are taught from an early age that the United States government will protect its people from censorship, as seen in the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights. However, this document was originally created to protect citizens from government censorship, not necessarily censorship coming from other citizens (5). Because of this, newer state legislation and court opinions either increase or decrease the ability to censor others in non-federal situations, and both public and private organizations get involved. One of the United States’ most iconic institutions, the public library, is a contested site in the discussion of censorship.

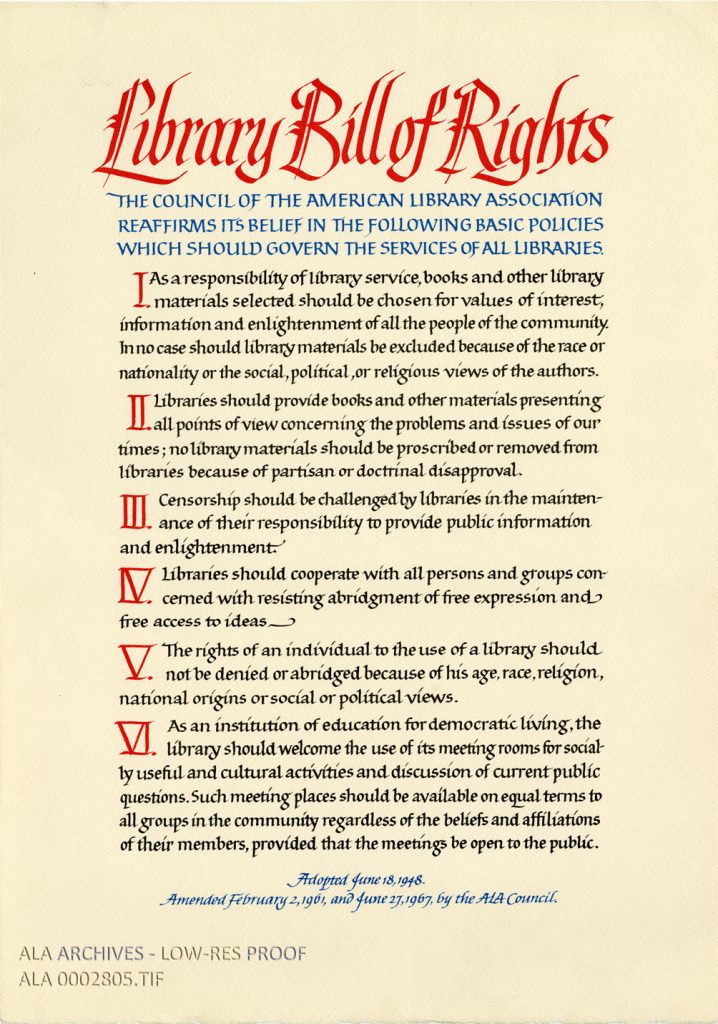

When the American Librarian Association Council accepted the Library Bill of Rights as a governing document in 1939, they also took a stand against censorship:

“Books and other library resources should be provided for the interest, information, and enlightenment of all people of the community the library serves. Materials should not be excluded because of the origin, background, or views of those contributing to their creation.” (4)

Librarians in particular are heavily scrutinized by their local communities for what they allow on their shelves. They must balance freedom of speech with serving their community, which has both positive and negative outcomes. For example, some librarians provide education and context to classic children’s books that have racist depictions of minority groups instead of removing the books from library shelves (1). However, not every librarian gets away with this, and some are fired for protesting censorship. Therefore, the ALA and its Office of Intellectual Freedom seeks to defend this right to protest and the librarians that support it.

To financially support these librarians, the Office of Intellectual Freedom created the LeRoy C. Merritt Humanitarian Fund (3). The fund was named in honor of Dr. LeRoy C. Merritt, a staunch defender of intellectual freedom and well-known editor of the ALA’s Newsletter on Intellectual Freedom (3). The Merritt Fund provides financial assistance to those librarians who are:

“Denied employment rights or discriminated against on the basis of gender, sexual orientation, race, color, creed, religion, age, disability, or place of national origin; or

“Denied employment rights because of defense of intellectual freedom; that is, threatened with loss of employment or discharged because of their stand for the cause of intellectual freedom, including promotion of freedom of the press, freedom of speech, the freedom of librarians to select items for their collections from all the world’s written and recorded information, and defense of privacy rights.” (3)

Recipients of the grant must fill out an application form and write an essay detailing why their case falls within the fund’s scope. They are also asked to pay back the full grant when they are financially able to. At most, the Board of Trustees may take up to a year to come to a decision on whether the applicant’s situation falls under the fund’s scope. If they decide the situation does not fall under the fund’s scope, they point the applicant towards other ALA offices that can help. The Board’s approved grants have helped many librarians in times of financial need due to discrimination or denied employment rights, such as in the case of Karla Shafer, former director of the Hooper Public Library in Nebraska. When Shafer started teaching English-classes to Spanish-speaking immigrants on her own time in a nearby town, the Hooper City Council forced her resignation by threatening to cut her hours and teaching abilities (2). She also lost her unemployment benefits because the city appealed to have them rescinded, and came into a dire personal financial situation (2). However, the Merritt Fund gave her a $5,000 grant to pay for home and legal bills, which helped her rebuild her life in Omaha (2).

The Merritt Fund is made possible solely through donations and repayment of grants. For more information on how to apply for a grant or donate, please visit the LeRoy C. Merritt Humanitarian Fund website. Physical records related to the Merritt Fund are available for viewing at the ALA Archives upon request.

- Andrew, Scottie. “Libraries oppose censorship. So they’re getting creative when it comes to offensive kids’ books.” CNN. March 3, 2021. https://www.cnn.com/2021/03/03/us/offensive-childrens-books-librarians-wellness-trnd/index.html.

- Berry, John W. “Merritt Fund Aids a Colleague in Distress.” American Libraries Magazine, January/February 2012. https://www.ala.org/aboutala/sites/ala.org.aboutala/files/content/affiliates/relatedgroups/merrittfund/merrittfundinaction/American%20Libraries%20article.pdf.

- “LeRoy C. Merritt Humanitarian Fund.” American Library Association. April 19, 2007. http://www.ala.org/aboutala/affiliates/relatedgroups/merrittfund/merritthumanitarian.

- “Library Bill of Rights.” American Library Association. June 30, 2006. http://www.ala.org/advocacy/intfreedom/librarybill.

- Purdy, Elizabeth R. “Censorship.” Middle Tennessee State University. 2009. https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/896/censorship.