From 1927 through 1930, as part of the “Curriculum Study” project, the American Library Association produced a series of textbooks to support library schools known under the series title as Library Curriculum Studies with Canadian American and Education Curriculum scholar Werrett Wallace Charters as the series editor. Each publication is rich in the experienced perspectives of library leaders of its time. Read on to learn more about early library school textbooks!

From the the first book’s “Director’s Information”, Ohio State University Education Professor W. W. Charters describes the development and intentions of the textbook series. In there, we learn that the series was coordinated by multiple ALA groups, including the ALA Board of Education of Librarianship (later Library Education Division), the Editorial Committee, the Advisory Committee of the Curriculum Study, and special committees for each textbook. In fact, the project was supported by two full-time staff too, including Harold F. Brigham and Anita M. Hostetter. With the first book as a sample, a 6-step process of developing and editing each textbook is outlined too.

- First: Staff identified the duties and traits of circulation librarians.

- Second: Staff conducted a literature review.

- Third: Staff observed “over fifty libraries” locally for examples of best practices.

- Fourth: A first draft was written during Spring and Summer 1926.

- Fifth: A mimeographed copy of the textbook was distributed among library schools for criticism and feedback.

- Sixth: Staff completed a final revision back at ALA Headquarters.

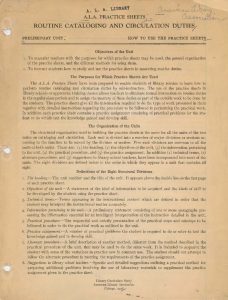

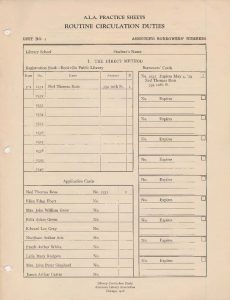

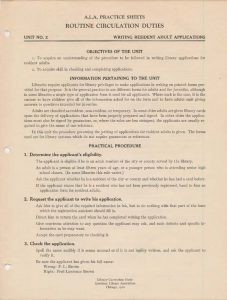

In this section, we also read that W. F. Rasche prepared a supplement series of practice sheets (seen above) for “ten of the most important routine duties”. Those practice sheets were published during the summer of 1926 for use in library schools and apprentice classes.

Published in 1927, Circulation Work in Public Libraries was written by Louisville Free Public Library Circulation Department Head Jennie M. Flexner. This 309-page publication includes 13 chapters by the author with 1 additional chapter “The Personality of the Circulation Librarian” written by W. W. Charters, a selected reference section, “thought questions” (for self-reflection on library practice), and an alphabetical subject index too. As described in the preface, as a book written for library school student audiences, the author emphasized 4 themes:

- The ideal of service through personal contact in the library;

- A constructively critical outlook on processes and routines;

- The possibility of a growing usefulness in the community;

- A professional and personal development through the study of traits.

In the book’s dedication page, readers can also see a tribute to the author’s father on his birthday.

Published in 1929, Reference Work was written by James I. Wyer (A.L.A. President, 1921-1922). This 315-page publication includes 19 chapters, a bibliography, “thought questions”, and an alphabetical subject index too. In the forward, the author distinguishes his textbook as complementary to the “Guide”, (also known as Guide to Reference Books). Of further use to readers, the author divided the book into 3 parts: Part I, Materials. The World of Print; Part II, Methods. The Use of Print; and Part II, Administration. In the book’s dedication page, readers can also see a tribute to the author’s long-time library home The New York State Library School.

Published in 1930, Introduction to Cataloging and the Classification of Books was written by University of Michigan Library Science Professor Margaret Mann. This 276-page publication includes 18 chapters, 2 appendices (How to Compute the Cost of Classifying and Cataloging Twenty Thousand Volumes and Comparative output of Cataloging in a Public and a University Library), and an alphabetical subject index too. True to its original purpose, in the second edition of the book (seen above), published in 1943, the author acknowledges that while additional audiences have included library school instructors, cataloging department staff, new cataloging assistants, library executives, and library trustees, the book has always been intended “for students who are beginning to study library science”. The author’s own early library education memories are briefly inscribed in the book’s dedication page, where readers can see a tribute to the author’s former colleague Katharine L. Sharp.

Published in 1930, The Library in the School was written by North Central High School librarian Lucile F. Fargo. This 453-page publication includes 14 chapters, questions and projects (no longer called “thought questions), a list of accredited library schools, and an alphabetical subject index too. This book also includes black-and-white photographs of modern school library settings. In the preface, the author describes the book as the successor to the previous national study of school libraries. While in the book’s dedication page, readers can see that while the author’s career took her to ALA Headquarters, she never forgot her formative experiences with children in the school library in Spokane, Washington.

Like Maragaret Mann’s Introduction to Cataloging and the Classification of Books, Lucile Fargo’s book would continue to be published in new editions beyond the original series. In 1947 and published in its 4th edition, in the book’s dedication page, readers can see both the enduring dedication to the author’s school library students as well as acknowledgement for her many colleagues in the American Association of School Librarians.

Before its publication, it was 1928 when a mimeographed copy of The Selection and Acquisition of Books for Libraries was written by Brown University assistant librarian Francis K. W. Drury. As series editor W. W. Charters described in an earlier section above, mimeographed editions of the Library Curriculum Studies series were circulated to library schools and scholars for criticism and review before the final draft was published for nationwide distribution. With this particular book, the author learned that there was enough material to produce two separate (but related) books!

In the two images above, readers can compare the table of contents from the editions from 1928 (left) and 1930 (right). Although most of the book’s general content might have remained, after receiving critical reviews from library schools, the book’s organization appears to have changed considerably. While the 1928 mimeographed copy has two sections and appears more like a manual, the 1930 edition might more closely resembles a textbook with chapters organized as essays on topics and accompanied by sample documents for student use.

Ultimately, the final draft was published in 1930, and this 369-page publication includes an alphabetical subject index too. When turning to the 1930 edition’s dedication page, readers can also see that the author chose to rededicate the final edition to his father (who passed in 1909). In the preface, the author proposes 10 purposes for a course in book selection:

- To analyze the nature of a community;

- To recognize the various uses to which books of varied types are to be put;

- To consider the character and policy of a library in adding books;

- To cultivate the power of judging and selecting books for purchase, with their value and suitability to readers in mind;

- To become familiar with the sources of information;

- To renew acquaintance with books and writers from the library angle;

- To develop ability to review, criticize, and annotate books for library purposes with sound judgement and facile expression;

- To decide where in the library organization book selection fits;

- To learn how to perform the necessary fundamental tasks of book selection;

- To scrutinize the mental and personal fitness of the selector.

In 1930, the second book, Order Work for Libraries was written by Francis K. W. Drury. This additional 260-page publication includes another 11 chapters, an alphabetical subject index, and 24 sample book order forms throughout the text. Like the previous book, the author proposes 5 reasons for a course in order work:

- To learn fundamental routines for acquiring purchases and gifts;

- To develop judgement in the various phases of order work, such as the selection of agents and the use of the national book trade bibliographies;

- To know how to count books at the accession desk;

- To understand the necessary processes in the mechanical preparation of books;

- To distinguish the essentials in statistics and reports.

In this book’s dedication page, readers can see the author’s appreciation for his colleagues at both the University of Illinois and the Brown University Library (where the author alludes to previous experiments in order work).

Published in 1930, Library Service for Children was written by Cleveland Public Library Director of Work with Children and Western Reserve University Library Science professor Effie L. Power. This 320-page publication includes 14 chapters, an alphabetical subject index, and 7 images which depict library service for children. Each chapter begins with a stated principle of children’s library services, before demonstrating how the principles work with examples. Although it was the last book in the Library Curriculum Studies series, this was the third book to continue to be published in multiple editions beyond the life of the original series.

In 1943, the second edition (now Work with Children in Public Libraries) was published. The new edition was a significantly changed book which included book criticism from over 30 librarians and the 1942 Children’s Charter in Wartime recommendations too. This book’s reorganization included the removal of book lists and an expansion of practice-based recommendations for children’s library service work. In the book’s dedication page, readers can also see the author’s continued appreciation for colleagues like Linda A. Eastman (A.L.A. President, 1928-1929).

The Library Curriculum Studies series produced not only 8 library school textbooks; but, it also produced multiple outstanding sources of library education which would continue to be reproduced independently for another decade and with an influence felt for years to come. This was also one of the first A.L.A. publication series to include book dedications which help readers appreciate the equally great impact which bibliophiles and librarians have had on both their library communities and on each other.

Copies Available at Your ALA Archives

Physical copies of Library Curriculum Studies are available for viewing at the ALA Archives. Please view the Record Series 13/10/22 database record entry, for more information.

Got Something to Donate to the Story So Far?

Many people have been involved in the long history of A.L.A. publications and library school education. Do you have any information about early library school textbook writers, collaborators, publications, or beneficiaries? Please contact us through social media. We and our readers would like to read about it.