As we look forward to book award ceremonies at the ALA Annual Conference this summer, we’re taking a moment to reflect on the history of one of the most prestigious children’s book awards, the Caldecott Medal. Established in 1937 to recognize the most distinguished American picture book for children, the first medal was awarded in 1938 to Dorothy P. Lathrop for the book, Animals of the Bible. However, the idea was first presented in 1935 in a letter by Frederic G. Melcher.

Melcher established the Newbery Medal in 1921 for “the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children.” While the medal was met was great enthusiasm, some felt that the award excluded books for younger children. Writing on behalf of the Association for Childhood Education, Professor May Hill Arbuthnot of Western Reserve University communicated this concern to Elizabeth Briggs, the Newbery Committee chair, in 1935.

Arbuthnot expressed the Association’s gratitude towards the Newbery Medal, citing that it stimulated better writing in children’s literature. However, she noted that the books chosen for the award “almost crossed over into the field of literature for young people rather than for children.”[1] The Association was concerned that books for young children were not being recognized. Arbuthnot pressed that there was a “hope that the Committee for the Newbery Award will consider carefully the field of literature for young children both because no award has ever been made at that level and also because the stimulation of such a distinction is greatly needed.”[2] Arbuthnot proposed that the Newbery could be awarded to books for the youngest children every so many years or that a Junior Newbery Award be established.

The letter came too late the sway any decisions made by the Newbery Committee for that awards cycle, but Briggs took the liberty of forwarding Arbuthnot’s letter to Melcher.[3] While Melcher did not weigh in on the decisions made by the Newbery selection committees, he remained involved in the awards process. He was a source of advice to committee chairs, paid for the medals to be struck and shipped, notified publishers of the award bestowed upon their authors, and encouraged publicity for Newbery, conscious of its prestige and influence. He was instantly intrigued by the idea of another award for literature for younger children.

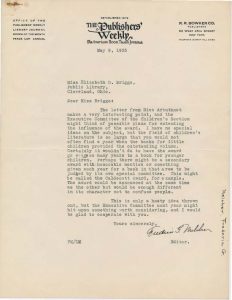

Writing to Briggs, Melcher mused, “… the Executive Committee of the Children’s Section might think of possible plans for extending the influence of the award.”[4] He immediately dismissed the idea of having an award only every so many years as he felt the volume of children’s literature was so great that it would produce an outstanding book. Instead, Melcher thought an award should be given every year to be announced at the same time as the Newbery, though it had to be different enough to distinguish the two awards. He even came up with the name, “This might be called the Caldecott Award, for example.”[5] Then in the closing sentence to his letter, Melcher wrote, “This is only a hasty idea thrown out …”[6]

In a letter less than ten sentences long, Melcher created a preliminary sketch for what would become the Randolph Caldecott Medal. In hindsight, Melcher’s own downplaying of his idea is humorous as his “hasty idea” gained traction and became one of ALA’s most enduring and prestigious book awards.

Sources

[1] May Hill Arbuthnot to Elizabeth Briggs, April 26, 1935, Awards File, 1934-2009, Record Series 24/2/8, Box 3, Folder: Newbery Medal Committee, 1935.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Elizabeth Briggs to May Hill Arbuthnot, May 7, 1935, Awards File, 1934-2009, Record Series 24/2/8, Box 3, Folder: Newbery Medal Committee, 1935.

[4] Frederic Melcher to Elizabeth Briggs, May 9, 1935, Awards File, 1934-2009, Record Series 24/2/8, Box 3, Folder: Newbery Medal Committee, 1935.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.