The letter “u” is a workhorse of the alphabet. It occurs so frequently that it will earn you only one point in Scrabble. Even so, it flies under the radar, escaping our notice. Now, texting threatens to elevate it to a pronoun. Have we underestimated this unassuming letter? The time has come for a closer look.

The letter derives from a character in the Phoenician script, attested from the eleventh century B.C.E., that originated as a pictogram of a hook, but also a sound transliterated as wāw. As the Phoenician script spread through the Mediterranean world, neighboring cultures adapted it to their own languages. In Greek, it became the upsilon—Υ, or υ in the lower case. In Latin, it became the v, which, despite its appearance, had the phonological value of our long u. The current, rounded form did not emerge in the Latin alphabet until the second century, when a book script developed that lost the angularity of earlier Roman scripts principally used for carving into stone.

The two forms coexisted throughout the medieval period. Its two forms, and the two strokes needed to form the letter, gave scholars much food for thought. A Carolingian scholar asked, “What is meant by its two strokes? And what do its two forms mean—the first oblique and the second straight? The first signifies evil speech and the last, good speech.” These same features prompted another scholar to the following ruminations: “How wide and spacious is life that leads to death! And how narrow and confined is the way that leads to life!”

We like the notion of a letter with an evil twin. Here are a few examples from our pre-1650 holdings. All are examples of the rounded form of u, but we hope the sentiments they help express do not lead you down the wayward path.

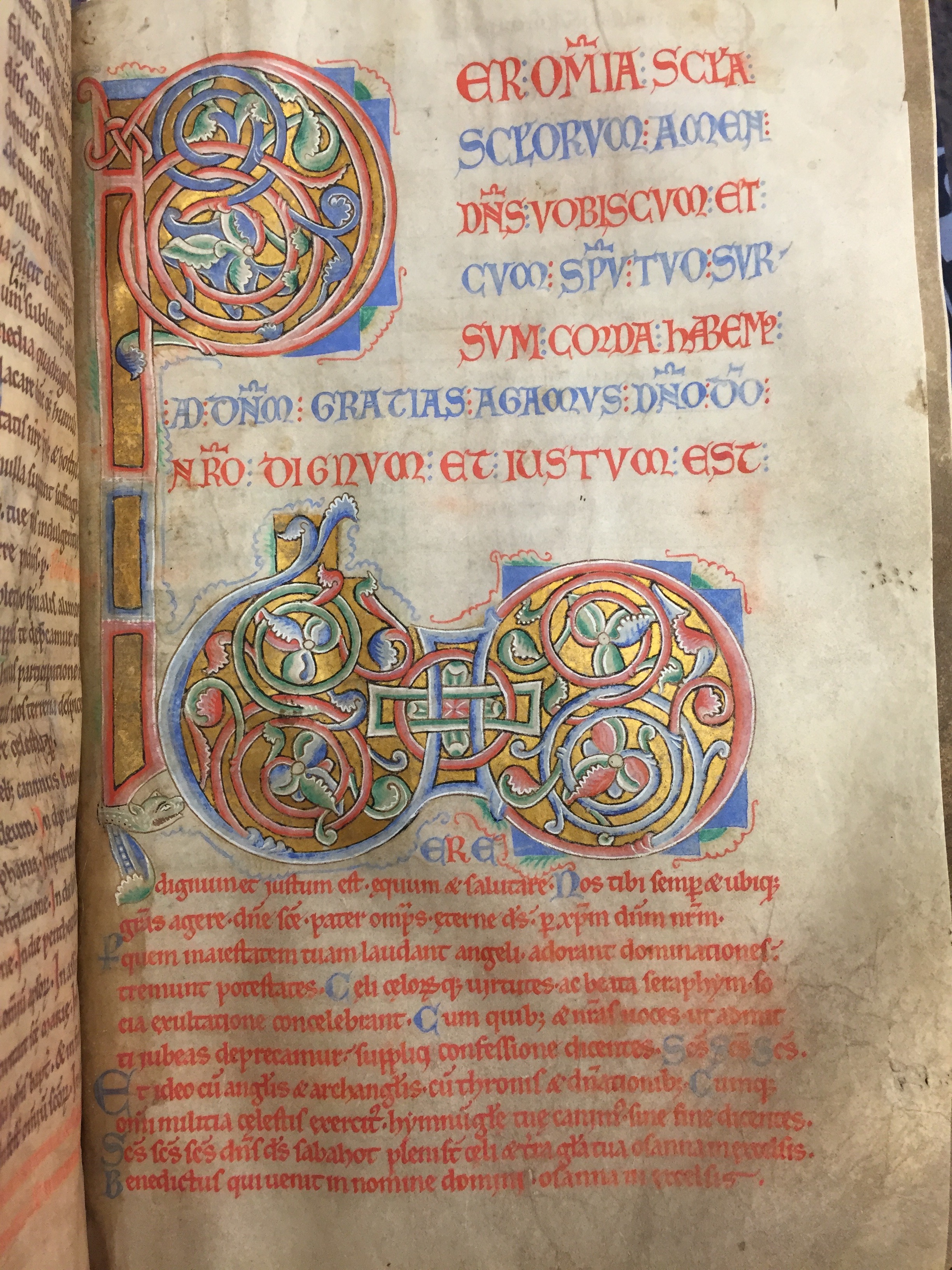

This manuscript contains the prayers, rubrics, and music necessary to celebrate Mass. This image is of the Preface of the Canon. The Canon of the Mass often received special attention from scribes and decorators as a way of acknowledging the sacrality of this portion of the rite. Decoration probably served a practical purpose as well. Since the Canon was the unvarying part of the mass, the priest needed to turn to it each time he celebrated mass. Large, colorful initials made it easier to find the necessary text.

This design is a monogram, when two letters combine to form a symbol. The two letters are u and d of the first two words of the prayer,uere dignum et iustus est [It is truly right and just]. The letters are hard to recognize because the artist has made them nearly symmetrical, but the priest would have had no difficulty recognizing this familiar prayer.

Notice also how, to the left of the monogram, the descender of the p sprouts both an acanthus leaf and a lizard’s head. The lizard looks like he is on his way over to take a bite out of the monogram, as if about to enact his own eucharistic feast.

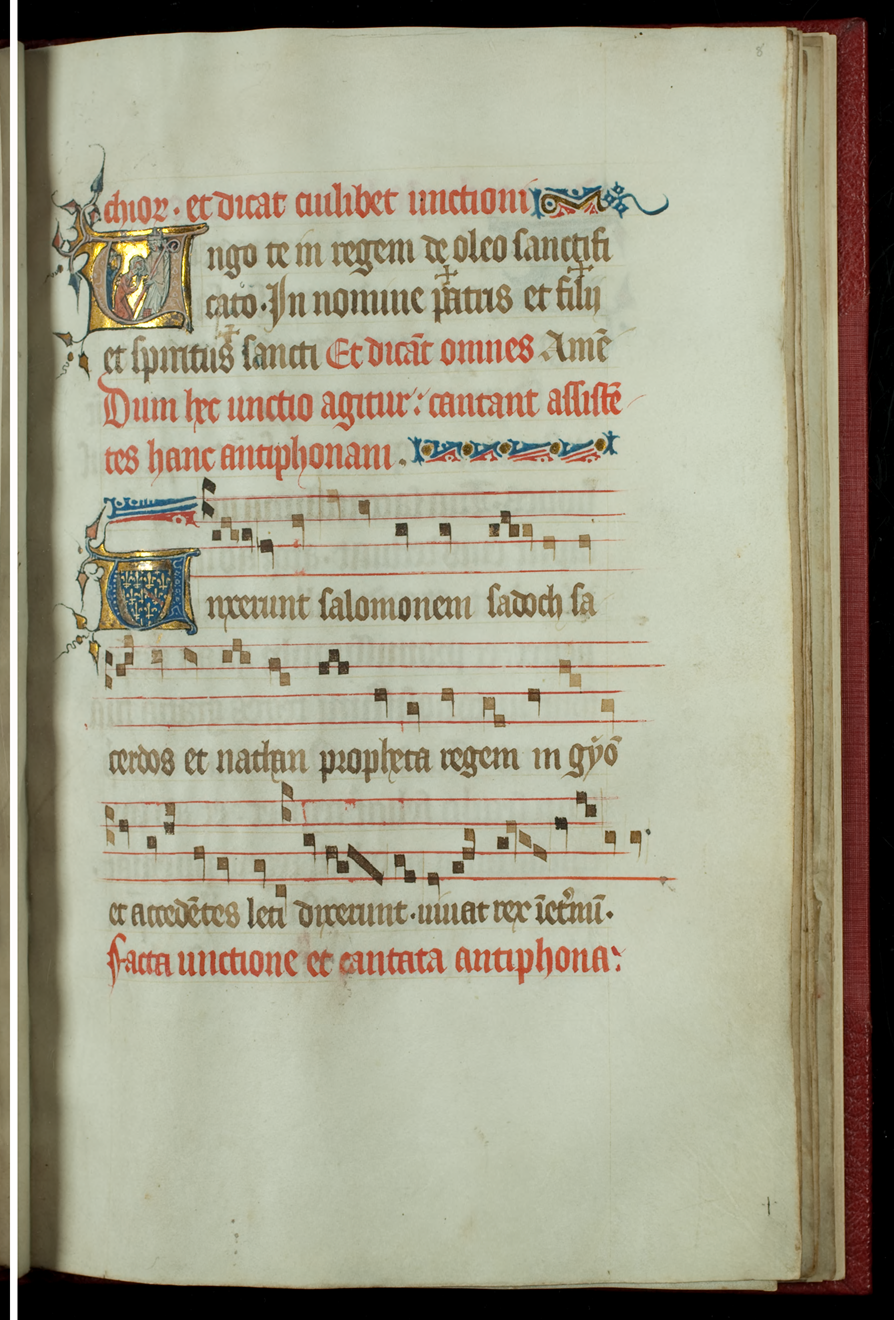

This manuscript contains the coronation rites of Charles IV and of his wife Jeanne d’Evreux, a rite that took place on May 11, 1326. The manuscript is particularly significant because only three other illustrated coronation rites have survived. Ours is lavishly illustrated, with over thirty historiated initials. Scholars think the book was probably prepared in advance of the event and intended as a souvenir for a relative, possibly one of Jeanne d’Evreux’s sisters or Charles IV’s sister, Isabella of England.

The manuscript is open to the prayers the archbishop recited as he anointed the king. The first initial introduces the text, Ungo te in regem de olio sanctificato [With chrism I anoint you king]. It is an historiated initial that depicts the archbishop, crozier in hand, as he anoints the king’s forehead. An attendant, only partly visible, stands behind the kneeling king.

Below the historiated initial there is a second initial that contains the arms of Jeanne d’Evreux. It introduces an antiphon sung by the archbishop’s attendants. This antiphon invokes the coronation of Solomon by Zadoch and Nathan in the 1 Kings. The juxtaposition of these two prayers unites the coronation of Charles IV, occuring in the here and now, to the coronation of Solomon, occuring in the timeless, ahistorical realm of the liturgy.

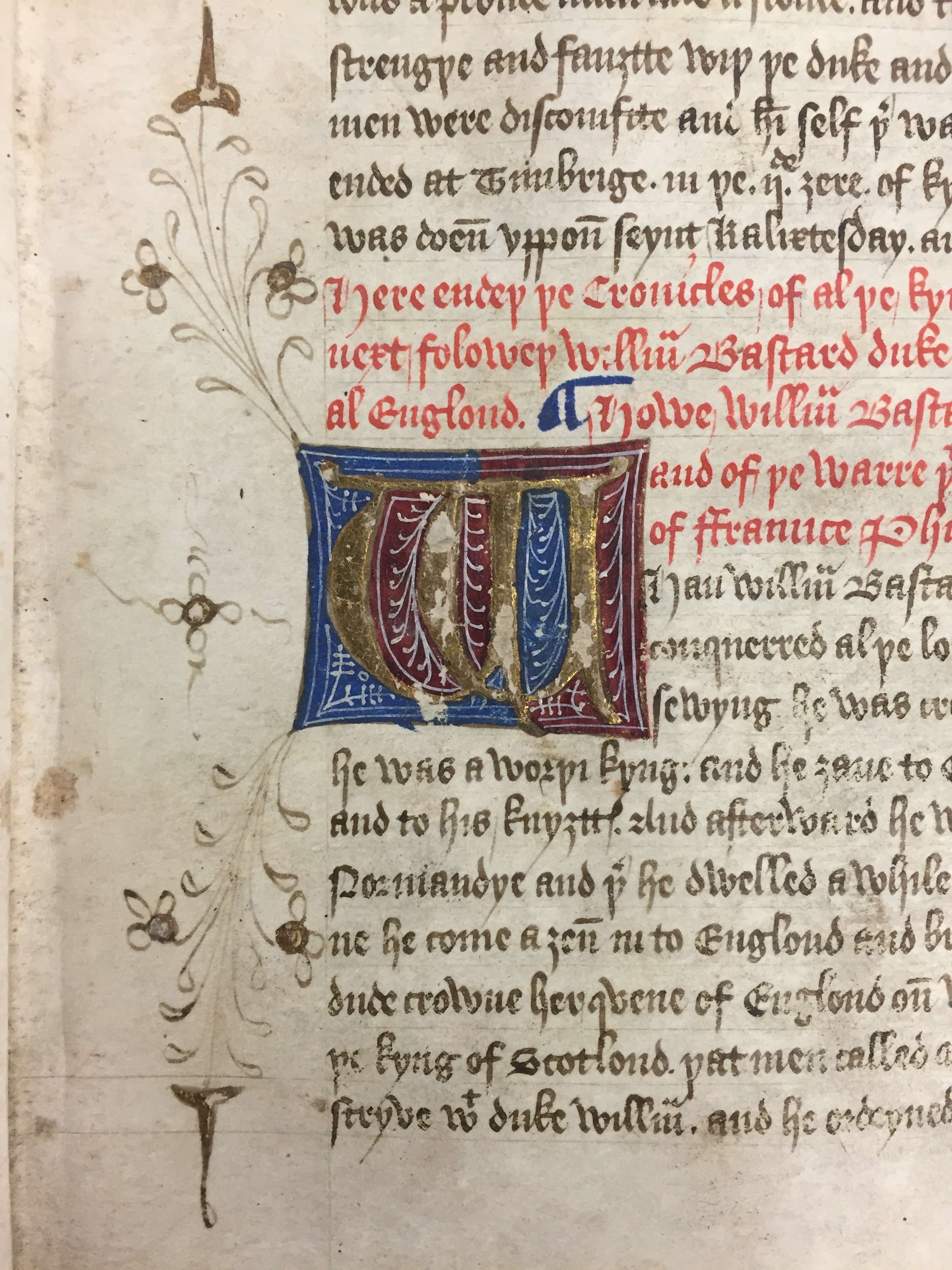

This manuscript contains a chronicle of the history of England commonly known as the prose Brut. The Brut draws on legend and history in equal parts, including figures such as Arthur and Merlin, along with Edward the Confessor and Harold Godwinson. The title derives from the figure of Brutus, the son of Aeneas and the legendary founder of Britain. The work was composed in the late thirteenth century in Anglo-Norman, but was later translated into Middle English with continuations to bring it up to date.

The manuscript is open to the section of the text that recounts the conquest of England. The section, introduced by a five-line initial, begins, “Whan Willia[m] Bastard duke of Normandye had conquerred al Þe londe uppon Cristmasseday next sewyng he was crowned king at Westmynst.” Since the w is the only decorated initial inside this manuscript aside from one at the text’s opening, we may assume that William the Conqueror was especially significant to the book’s first owner.

The letter w was not part of the Latin alphabet, but was introduced in English during the Middle Ages. First a convention arose of doubling the u when it served as a consonant. Eventually, it became a letter in its own right. That its form is of a double v and its name the double u attests to the interchangablilty of these letters throughout the Middle Ages.

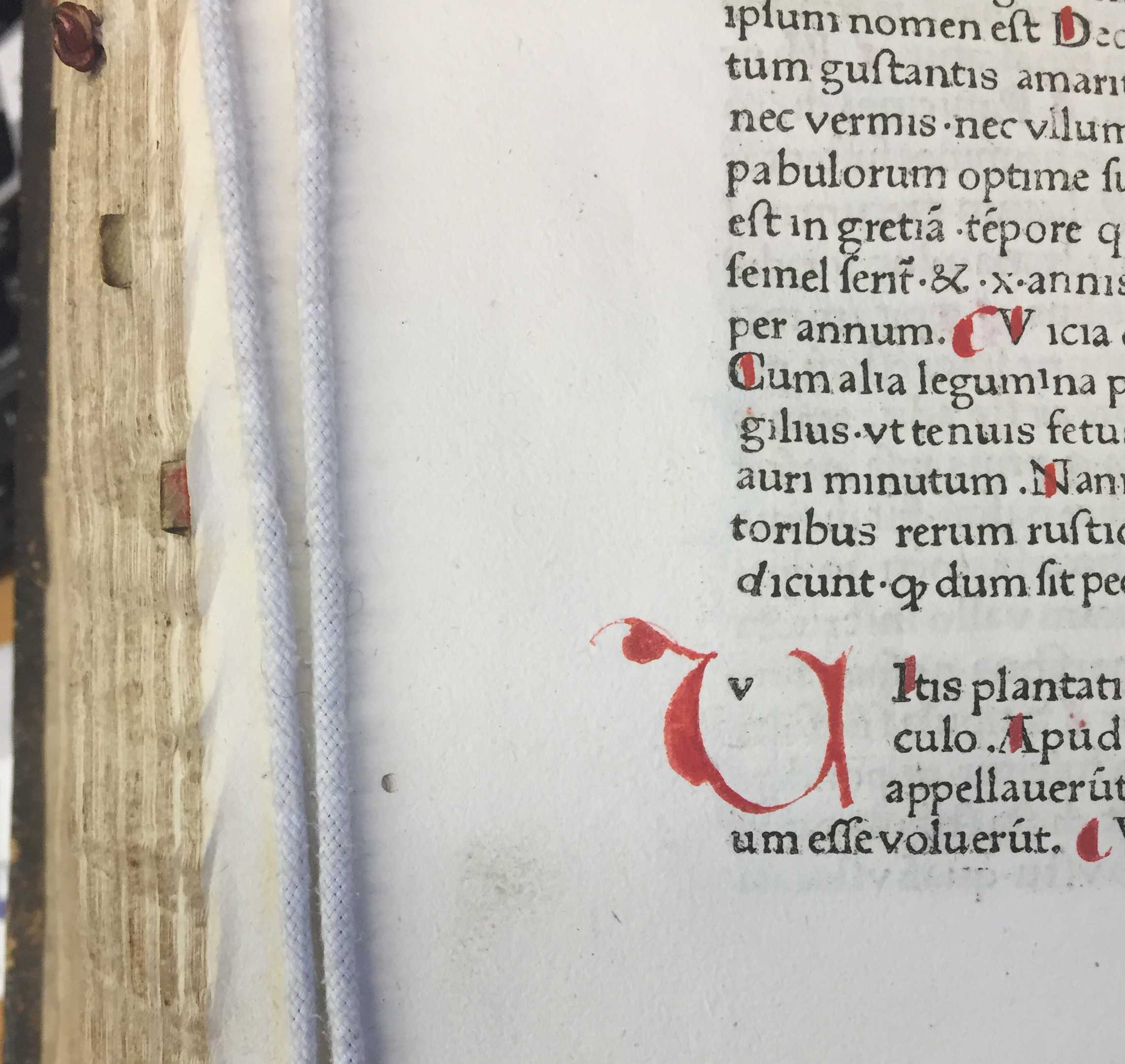

Isidore of Seville’s encyclopedia, commonly known as the Etymologies, was a popular textbook throughout the Middle Ages and beyond. According to Stephen Barney, the work’s most recent editor, “it was the most influential book, after the Bible…for nearly a thousand years.” It gathers all knowledge into twenty books, ranging from the succintly titled “Grammar” (Book 1) to the more unwieldy, “Tables, Foodstuffs, Drink and their Vessels, Vessels for Wine, Water, and Oil, Vessels of Cooks, Bakers and Lamps, Beds, Chairs, Vehicles, Rural and Garden Implements, Equestrian Equipment” (Book 20). Along the way it stops at the “Cosmos and its Parts” (Book 13).

The printer left space for initials to be hand-painted later, as well as small guide letters so the artist would know what letter to make. On this page, the guide letter is the straight form of the letter u while the initial painted by the decorator is the rounded form. JC

Missal, ca. 12th century. Pre-1650 MS 0101

Ordo ad consecrandum et coronandum regem et reginam Franciae. France, approximately 1326-1330. Pre-1650 MS 0124

[Here begynneth a boke in Englysshe tonge called Brute of Ingelond, or, The cronycles of Ingelond.] England, ca. 1450. Pre-1650 MS 0116

Isidore of Seville. d. 636. Isidori Iunioris Hispalensis Episcopi Epistola Liber etimologiarum. Augsburg: Ginther Zainer, 19 November 1472.Incunabula Q. 871 I5e.Z

What a fascinating entry! Can you share from where the Carolingian scholars’ quotes in the third paragraph came?

Awesome! Its actually remarkable piece of writing, I have got much clear idea

regarding from this post.