By Elissa B.G. Mullins

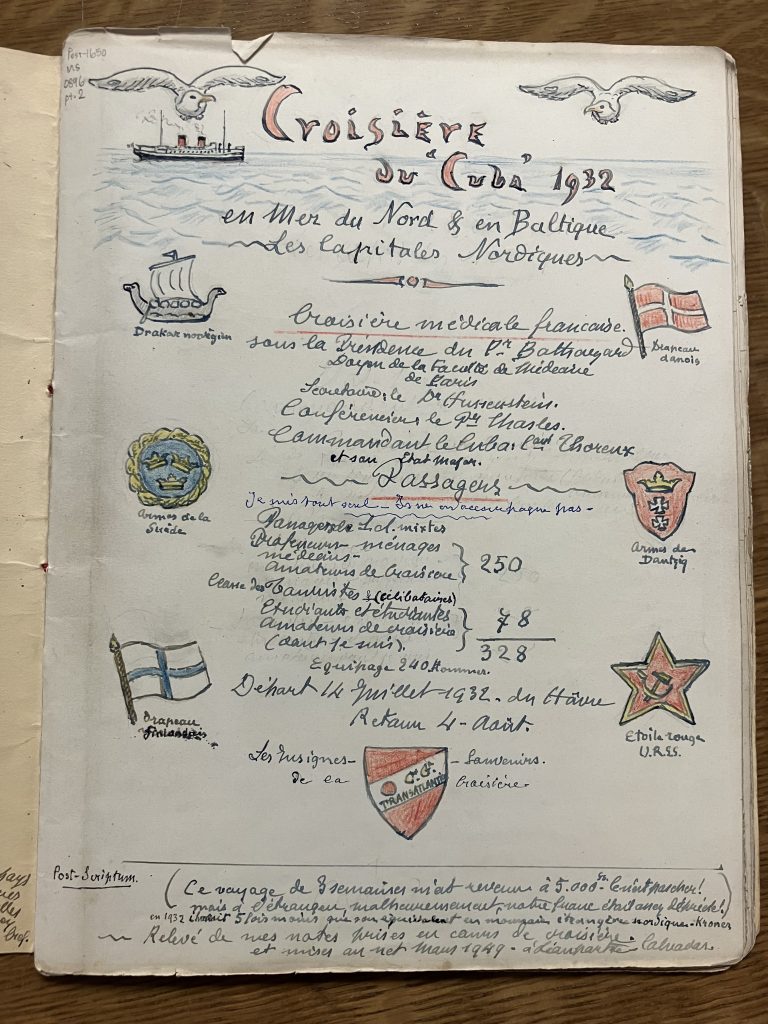

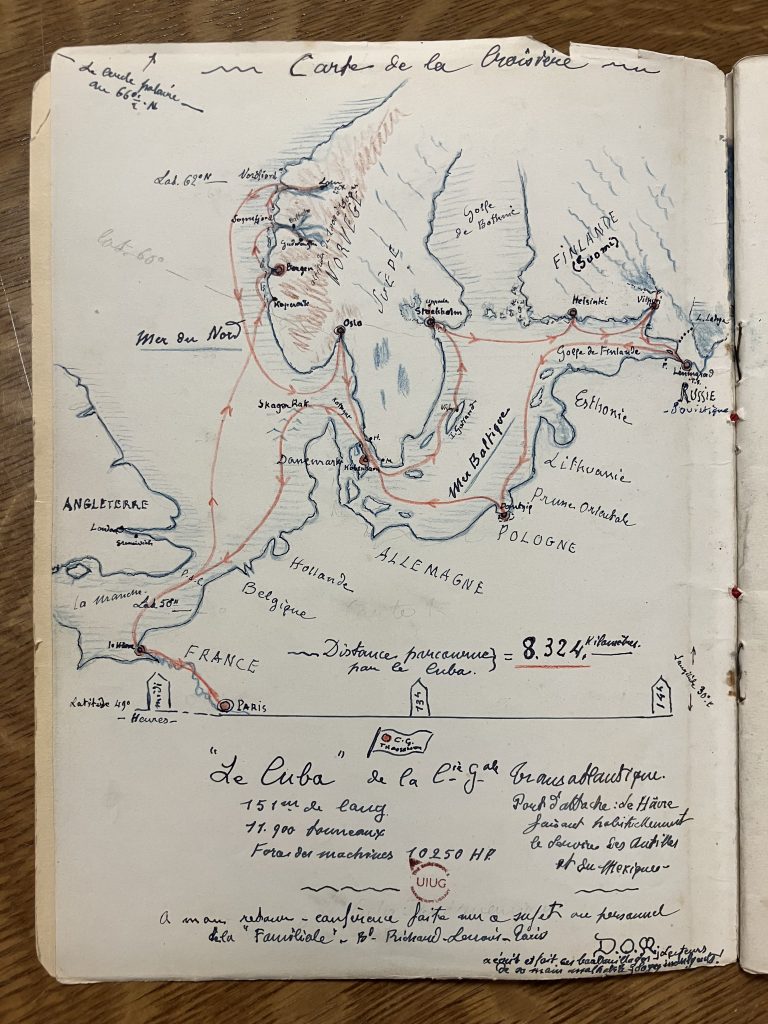

Climb aboard the S.S. Cuba for a rare glimpse behind the iron curtain through the keen eyes and profusely detailed journals of a French physician, Dr. O. Ménard (Post-1650 MS 0896). In July 1932, the S.S. Cuba was privately chartered by a French medical society for a special tour of Scandinavia, the Baltics, and Russia—the first French tourist group (according to Ménard) permitted by Russian authorities to enter Saint Petersburg (then Leningrad).

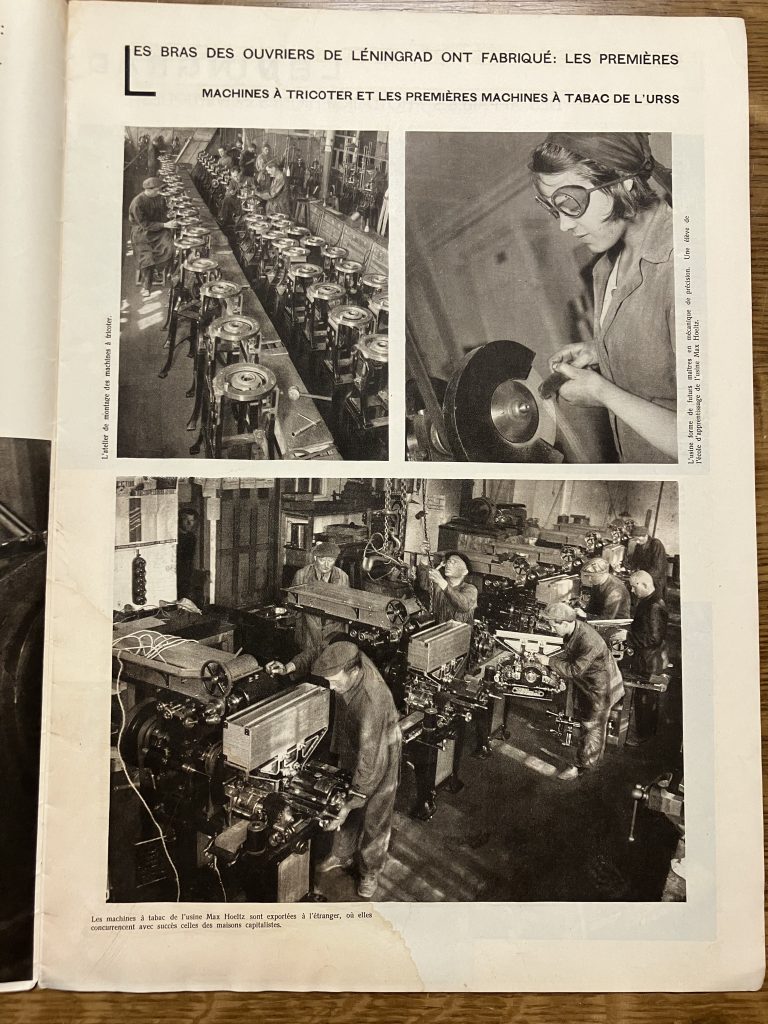

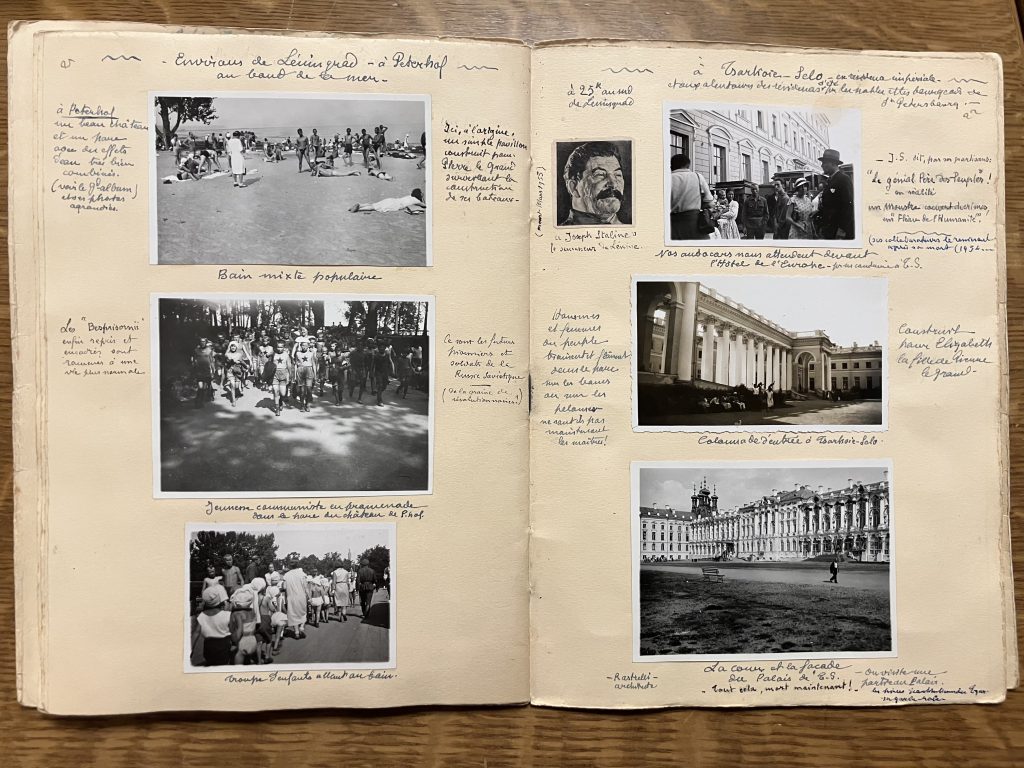

Ménard crafted a detailed account of his travels, describing historic monuments, landscapes, ways of life, and intimations of contemporary political events in Norway, Sweden, Finland, Poland, Denmark, and Russia. His journals have traveled, at last, to our library—replete with personal observations, skillfully illustrated with color drawings, and accompanied by printed ephemera, 107 mounted black and white photographs, and a French edition of a large propaganda magazine, “U.R.S.S. en construction.”

As one of the earliest tourists in Russia after the 1917 Revolution, Ménard’s account offers a glimpse of Soviet Russia under Stalin before World War II. The visit to Leningrad takes place under the strict control of the government’s “Intourist” agency, which guided and monitored foreigners’ movements and activities. Tourists were permitted to meet people from their own sectors of life; the French physicians were allowed to tour Soviet hospitals and medical facilities.

Photography was restricted; Ménard notes in the margin of his journal, “See my photographs taken secretly!” He writes that their tour guide follows the itinerary to the letter and permits them no freedom, and “never fails to mention the exploits of the Revolution.”

Tourism was designed to promote Soviet ideology and to vaunt Russian advances in industrialization—all the while millions of people across the Soviet Union (particularly in Ukraine and Kazakhstan) were dying from starvation. Though Ménard was unaware of the famine and the full extent of the Soviet government’s duplicity, he sees through the carefully scripted image promoted by his tour guides, and in his journal describes an impoverished society in the throes of reformation and uncertainty.

He writes (in French): “We do not regret the opportunity of seeing this people of slaves which, having suppressed God, destroyed its leaders, elites, and even the bourgeois class, is now astonished at its victory, and wonders how it will overcome the difficulties of life with a different society and a new mysticism.”