By Molly Banwart

Today we’re looking at two seminal printed isolarii, or island books, from the late 15th and mid-16th centuries. The isolarii genre can be thought of as an encyclopedia of islands containing maps along with text descriptions of significant history, maritime information, mythology, and an analysis of the physical geography of the land. Although primarily intended for sailors, isolarii were read by many audiences, including those reading for simple pleasure.

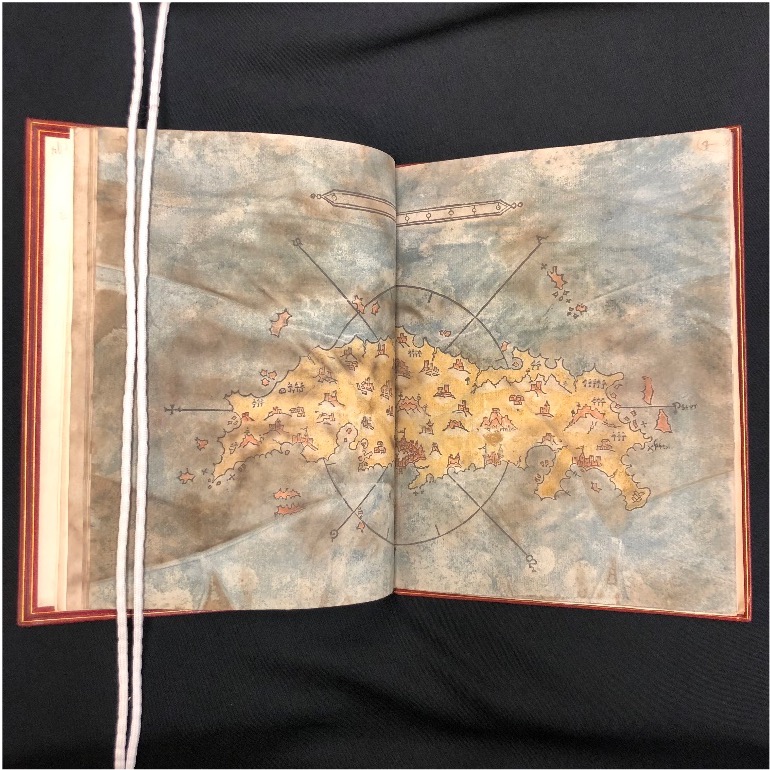

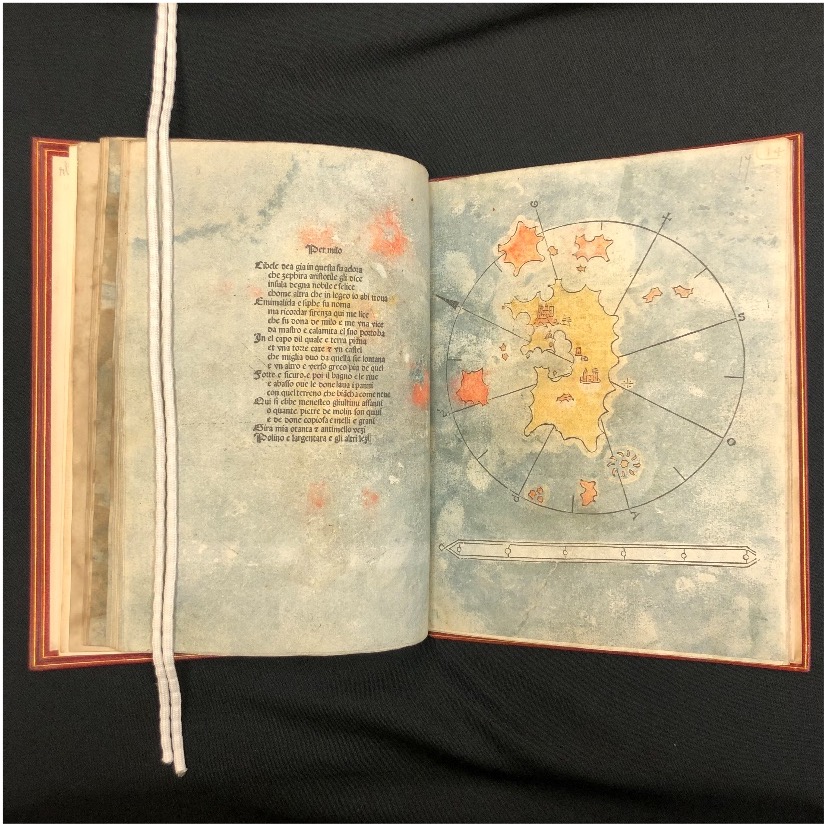

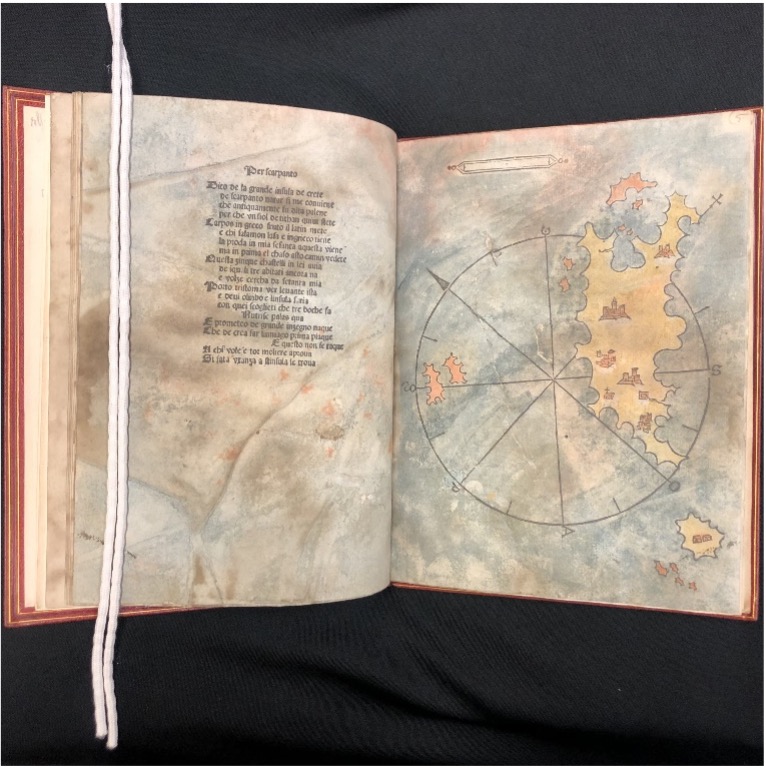

Bartolommeo da li Sonetti’s Isolario (Incunabula 852 B285Oi1485), published before 1485, includes wood engravings of 49 maps of islands in the Greek archipelago, accompanied by commentaries on geography, history, and archaeology of each place in the form of sonnets, a common practice in geographical works of the 14th and 15th centuries.

The author identifies himself as the “bon venitian bartholomio” in the opening sonnets of the book, and following its printing, scholars have called him Bartolommeo da li Sonetti, or Bartolommeo from the Sonnets. Bartolommeo’s actual identity has been argued as being either Bartolomeo Zamberti, a known Venetian translator of Classical works, or Bartolomeo Turco, a peer of Leonardo da Vinci. While his identity is disputed, what we do know from his introductory sonnet is that Bartolommeo made about fifteen journeys to the Aegean Islands and was quite familiar with the islands that he drew maps of for his work. The book borrowed many genre features of Buondelmonti’s pioneering manuscript isolario, such as constructing each chart on a compass rose and indicating rocks and treacherous waters with crosses and dots. However, Bartolommeo’s is the first printed isolario, and its ease of production lent itself to be more successful in mass practical usage. The maps helped sailors in their voyages, showing reefs and other perilous spots.

While the maps are historically significant in their popular use, the accompanying text is also quite notable: the sonnets are written in a lively vernacular, and render place names according to contemporary pronunciation, as opposed to their archaic forms. Yet at the same time, scholars note that the sonnets retain a lyrical quality that call back to the styles of Virgil and Dante.

The copy of Bartolommeo da li Sonetti’s Isolario held at the RBML is one of only a handful that have the woodblock illustrations hand-colored, and subsequent water damage has bled the colors onto neighboring pages, adding an additional, unique layer of liveliness to the already linguistically vibrant accompanying text.

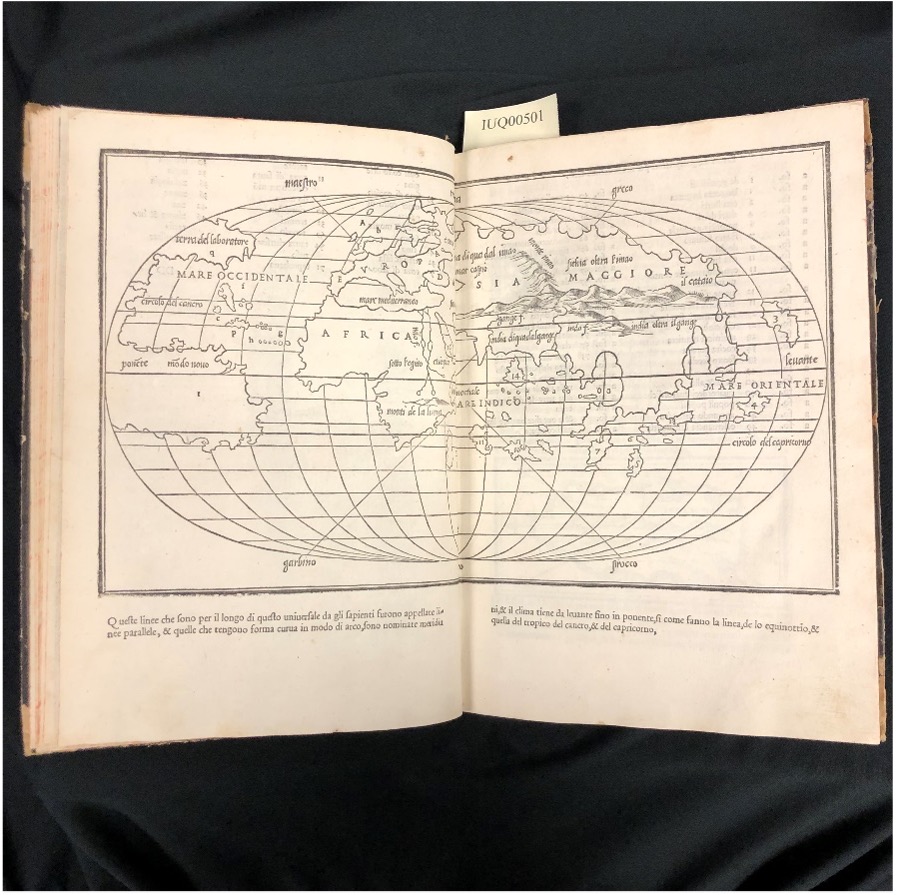

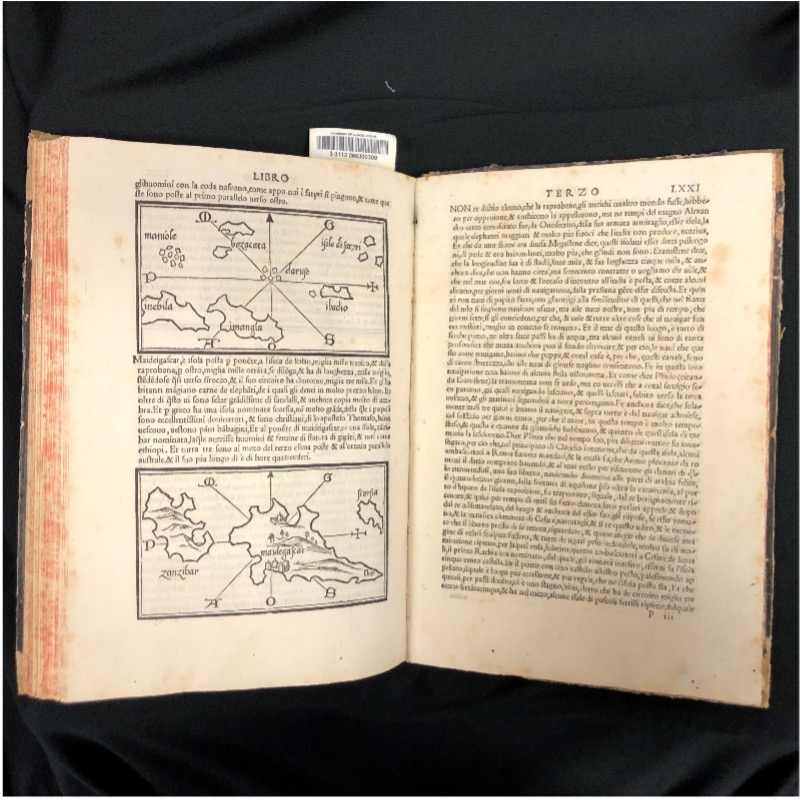

The genre of isolarii would continue to grow with the 1528 printing of Libro di Benedetto Bordone: nel qual si ragiona de tutte l’isole del mondo con li lor nomi antichi & moderni, historie, fauole, & modi del loro uiuere, & in qual parte del mare stanno, & in qual parallelo & clima giacciono (IUQ00501), which translates: Book of Benedetto Bordone: in which we reason of all the islands of the world, with their ancient & modern names, histories, fables, & ways of life, & in which part of the sea they are, & in what parallel & climate they lie.

By the mid-16th century, Europe was beginning its journey into the Age of Sail, in which global trade out of Europe began to flourish by means of a growing maritime industry. Bordone expanded the isolarii genre beyond the Mediterranean, and the results in his work ranged from the Caribbean islands of the New World to the coasts of Africa, and included the earliest known printed map of Japan (called Ciampagu, from the Chinese jihpen-kuo). Sailors continued to use the book to plan economically strategic routes for supplies and trading, while many “armchair cartographers” of Europe reveled in its abundant information of the expanding world.