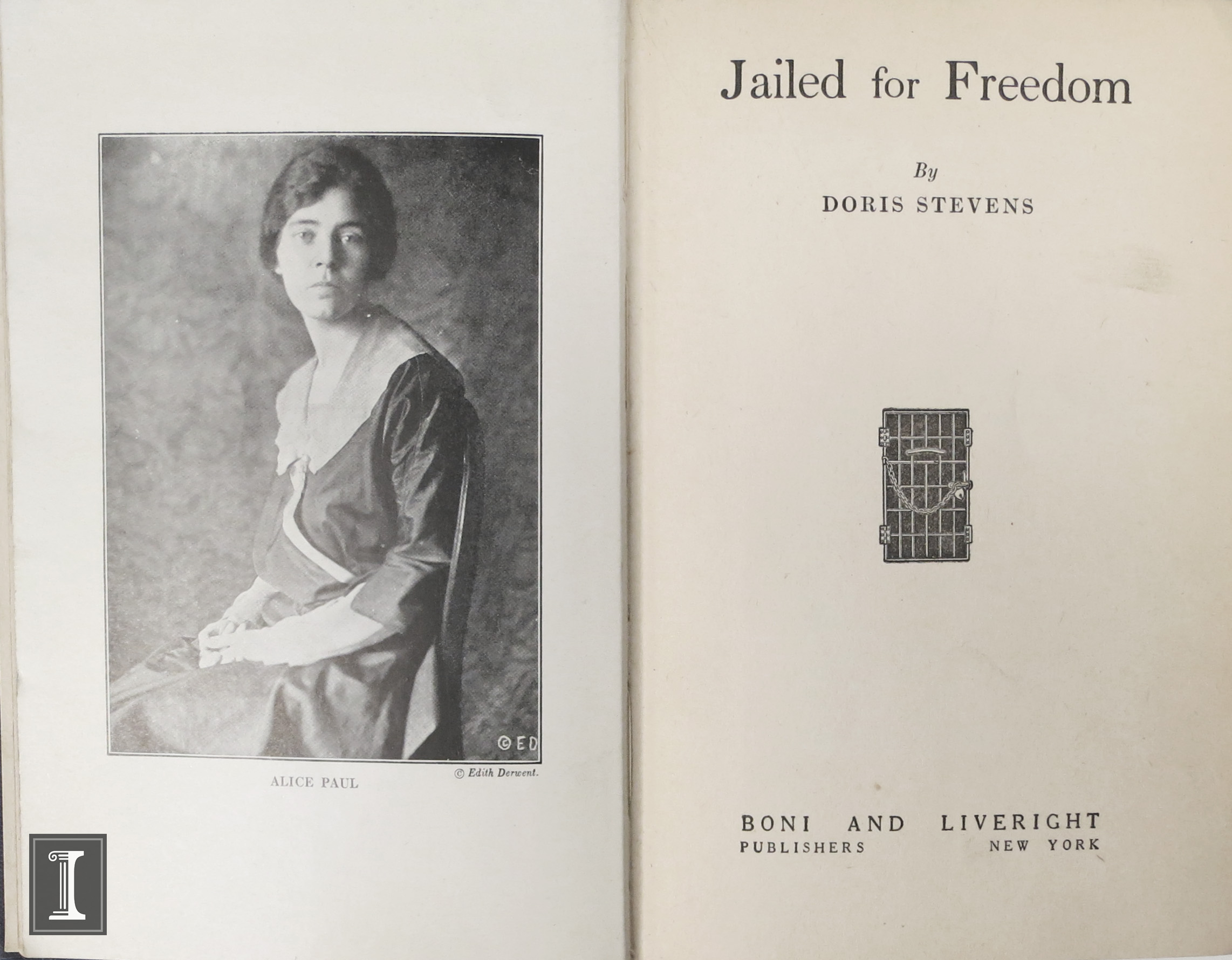

Congress proposed the Nineteenth Amendment in June 1919. To commemorate this event, we are looking at a important book, Jailed for Freedom, by suffragist Doris Stevens.

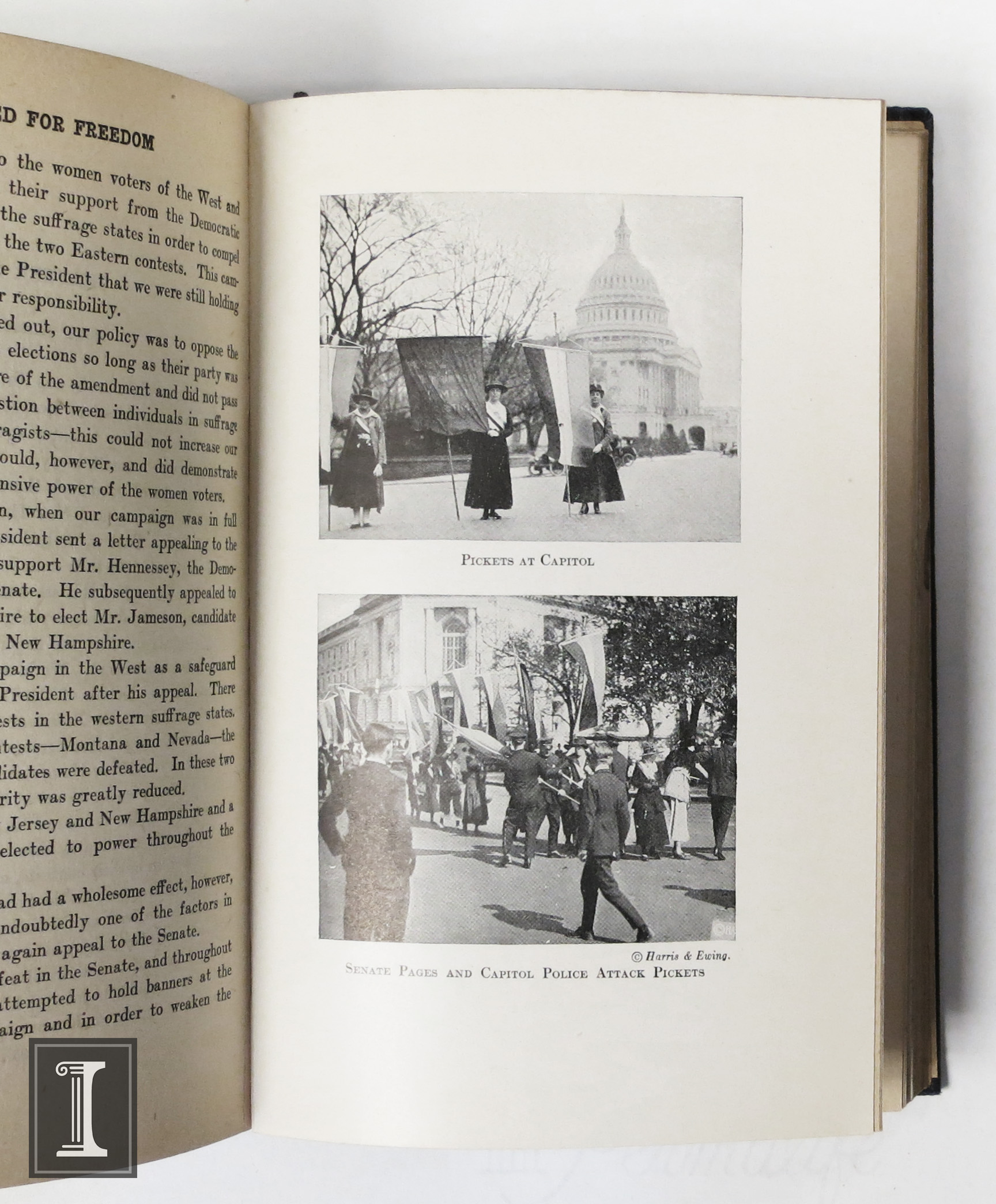

Born in 1892 in Nebraska, Doris Stevens attended Oberlin College and briefly worked as a social worker and teacher before joining the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). When the National Woman’s Party (NWP) was formed in 1916, she served on the executive board. In January of 1917, members of the NWP took their cause to the gates of the White House where they hoped to ultimately sway President Woodrow Wilson on the issue of voting rights. They protested six days a week for almost two-and-a-half years, acquiring the nickname “Silent Sentinels” for their mute method of protesting. At first the picketers were tolerated, but when the United States formally entered World War I just a few months later, they were criticized by some as being unpatriotic and distracting from the war effort. Stevens strongly believed that the protests should not stop for the war, and felt that it was hypocritical of Wilson to champion democracy overseas while denying it to half of American citizens at home.

In July of that year, law enforcement began to arrest protesters, ostensibly for obstructing traffic. Stevens herself was arrested and sentenced to sixty days in the Occoquan Workhouse in Washington, D.C. She served three and when released, dedicated herself to publicizing the inhumane treatment of NWP members serving longer sentences. Activists like Lucy Burns were given spoiled food, beaten by prison guards, subjected to solitary confinement, and force-fed when they continued to protest via hunger strikes. Stevens called the treatment “administrative terrorism.” The prisoners were finally released in late November 1917.

Stevens reports in Jailed for Freedom: “Immediately following the release of the prisoners and the magnificent demonstration of public support of them, culminating at the mass meeting recorded in the preceding chapter, political events happened thick and fast” (248). In September 1918, Wilson came out in support of women’s suffrage, framing it, incidentally, as vital to the war effort. The war, he said, “could not have been fought, either by the other nations engaged or by America, if it had not been for the services of women–services rendered in every sphere–not merely in the fields of effort in which we have been accustomed to see them work, but wherever men have worked and upon the very skirts and edges of the battle itself.” He told Congress that, “the extension of suffrage to women as vitally essential to the successful prosecution of this great war of humanity in which we are engaged …”

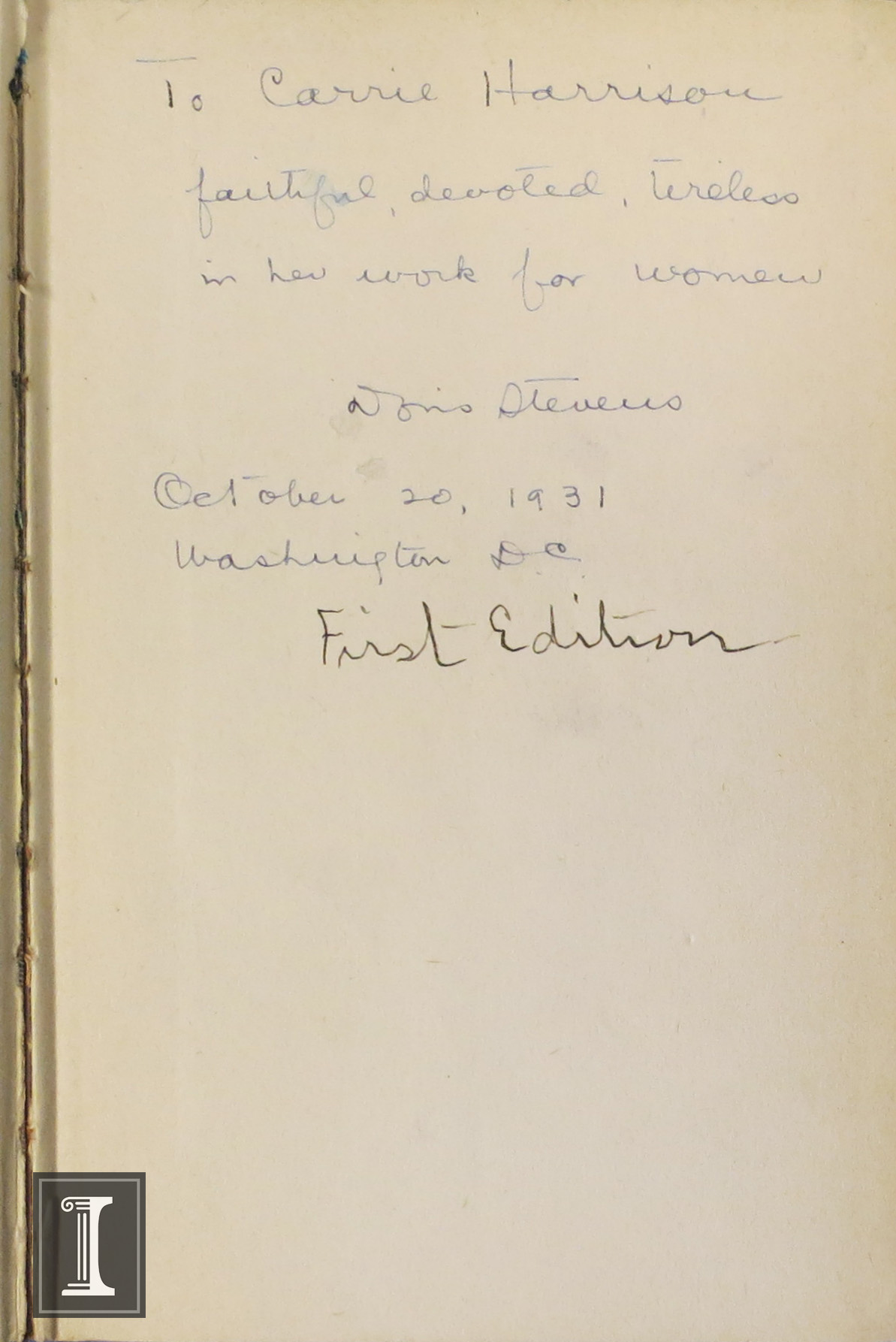

RBML holds a first edition of Jailed for Freedom, wherein Stevens describes the protests and the events leading up to them, the suffragists’ prison experiences, and finally the amendment’s June 1919 ratification. The book is inscribed by Stevens “To Carrie Harrison faithful, devoted, tireless in her work for women” and dated “October 20, 1931 Washington D.C.” The dedicatee is Carrie Harrison of the Department of Agriculture in Washington, D.C., an Iowa native who studied at Wellesley College and Cornell University. She was a dedicated botanist and a member of the College Equal Suffrage League (CESL). She is also credited with coining the 4-H organization’s motto “To make the best better.” SL

Stevens, Doris. Jailed for Freedom. New York : Boni and Liveright, 1920.

BASK 324.3 ST4J: https://i-share-uiu.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01CARLI_UIU/gpjosq/alma99355617612205899