Explore historic Chicago newspapers published in Croation, Czech, German, Lithuanian, Polish, and Slovenian through Illinois Digital Newspaper Collections and Chronicling America.

By 1900, the mark of mass immigration to the United States on Chicago’s population was impressive. Of the city’s 1.7 million inhabitants, three-fourths were immigrants or were the children of immigrants.[1] It’s difficult to imagine what life was like at this point in the city’s history. Books, museums, and films help, but there’s one source that’s been traditionally overlooked: the foreign-language press.[2]

Chicago’s Foreign-Language Newspapers

At the turn of the 20th century, Chicago was home to an array of foreign-language newspapers, published daily, weekly, and monthly. By 1930, after the start of a slow decline in the number of dailies, there were 38 being published in the city. 25 of these were published in 12 foreign languages, including Yiddish, Slovak, Lithuanian, Czech, and Polish, to name some.[3] While English-language titles tended to have larger circulations,[4] the number of languages reveals a diverse collection of communities.

But measuring the diversity of perspectives using the metric of language would, of course, be shortsighted. A quick look at the city’s early foreign-language press at work brings to light the complex threads that make the history of Chicago’s communities so rich. It also blurs this history’s geographic boundaries.

Considering some perspectives represented in historic newspapers, created by and for this community, may give us a more nuanced understanding of the lives of its members, or at least of the media environment they shared, in the early 20th century.

Unity through the Polish-Language Press

While Chicago’s Polish-language newspapers met informational needs by providing news in the Polish language, they were also used to sustain the interests of various cultural organizations that played a key role in helping Polish immigrants adjust to their new surroundings, through supplying benefits, such as insurance, educational programs, or spiritual congregation. Several of these organizations aimed to establish unity amongst Chicago Poles and took differing approaches to achieve this goal.[5] These approaches are reflected in the “editorial stances” of some of Chicago’s historic Polish-language newspapers, added in 2018, to Illinois Digital Newspaper Collections and Chronicling America.

Characterizing these stances in the following ways is not meant to capture exhaustive or mutually exclusive ways of defining individual or communal identity. However, it may be useful in highlighting the presence of some deep-rooted and sometimes-competing interests amongst members of Chicago Polonia, Chicago’s Polish diaspora, at the turn of the 20th century.

Religion

The Roman Catholic Church has a deep history in Poland, being inextricably tied to the formation of Polish statehood, and was a major part of Polish American life at the time. Dziennik Chicagoski (“Chicago Daily News”) was a daily paper that ran from 1890-1971 and promoted Poles’ continued adherence to the Catholic faith. As the editors of Dziennik Chicagoski wrote, on July 25, 1892: “To be a Pole one does not necessarily have to be a Catholic; that is true. Yet the least indifference to Catholicism is harmful to our nationality.”[6]

The Polish-language weekly, the Telegraf, founded in 1892, varied in affiliation due to changes in personnel, beginning as Democratic and then changing to Republican in 1903. The paper switched back to Democratic in 1918, when the paper was bought by Edward L. Kolakowski. [7] During its first Democratic period, the Telegraf had ties with the Polish Roman Catholic Union (PRCU), a Chicago-based fraternal organization founded in 1873 and still in existence. While there was some disagreement about the inclusivity of its membership in its early formation, in its beginnings the PRCU limited membership to Roman Catholics. Its founding motto was “Bóg I Ojczyna” or “God and Fatherland.” [8] The Telegraf ran until 1939.

Nationality

The Polish National Alliance (PNA), another fraternal organization painted by some scholars as rival to the PRCU, was established in 1880 and still exists today.[9] The PNA did not limit its membership to practicing Catholics, including members of other faiths, atheists, and those with different political leanings.[10]

The society “encouraged organizational unity among Polish immigrants,” prioritizing the ideal of “ethnic solidarity.”[11] Zgoda (“Harmony”), established in 1881, was the PNA’s weekly paper and reported news pertaining to both the United States and Poland.[12] Zgoda included articles critical of the clergy. One article, entitled, “Precz ze Zdrajcami” (“Down with Traitors”), claimed that clergy members should not use their positions for comfort, but to empower “the voice of the people.”[13] The paper still runs today, having transformed into the PNA’s quarterly magazine.

Members of the Polish Nationalist Party established Dziennek narodowy (“National Daily News”) in 1908, a daily paper running until 1923 that contested the influence of the Catholic Church on the Polish community.[14] Zgoda and Dziennek narodowy sought Polish unity by promoting the independence of the Polish nation, one demarcated by an ethnic, cultural, or political identity separate from religious affiliation. Poland had been partitioned and under the control of Prussia, Russia, and Austria since the 1790s. The sense of unity promoted by these papers was closely tied to the achievement of the country’s independence amidst foreign occupation.[15]

Class

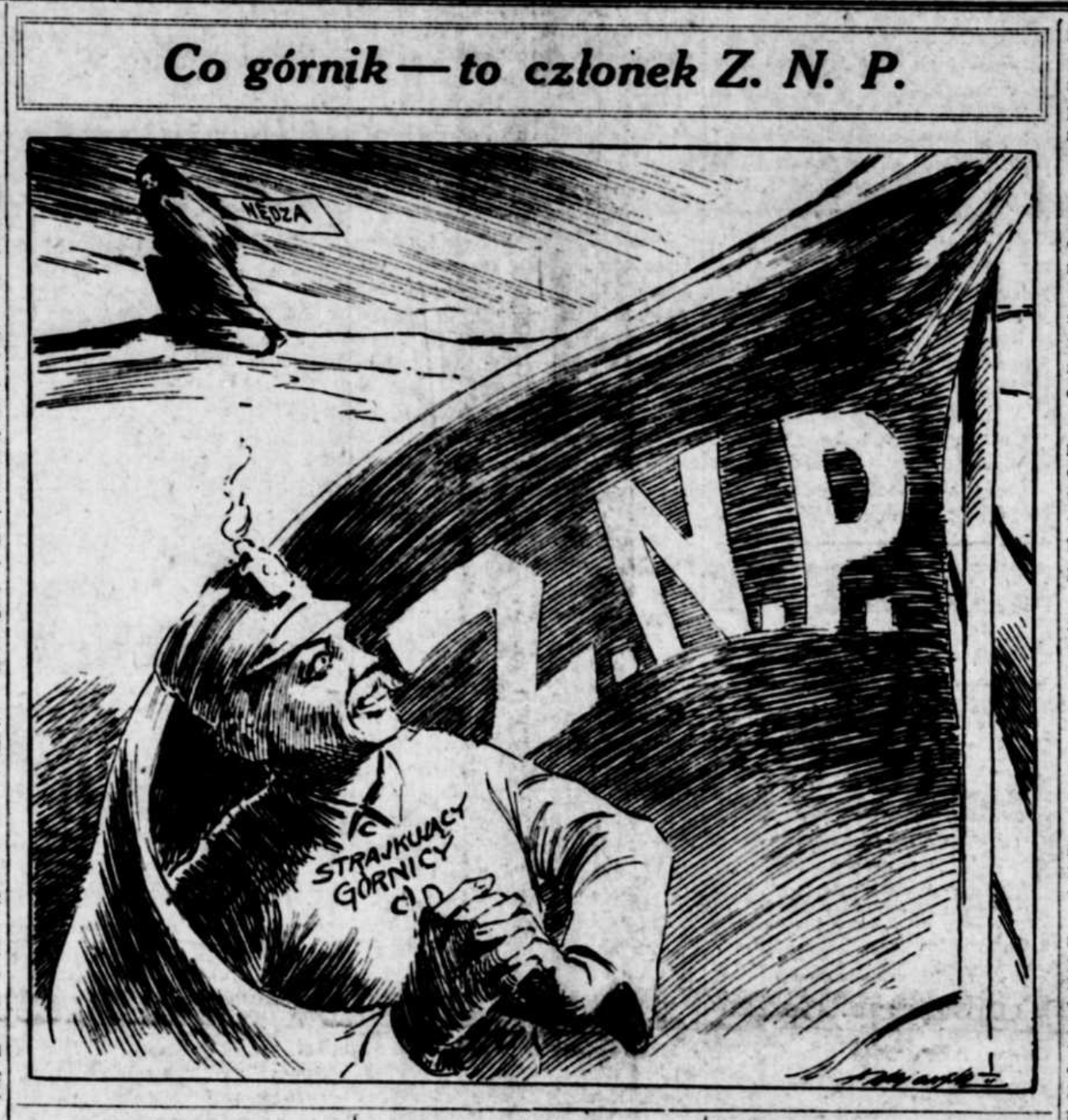

The vast majority of Polish immigrants were firmly embedded within the American working class. In its beginnings, the PNA’s weekly, Zgoda, also published news related to the labor movement, with a section dedicated to this content. This content was then moved to its daily paper, Dziennik Zwiazkowy, in 1908. [16]

Dziennik Chicagoski openly questioned Polish papers reporting on movements deemed socialist in nature.[17] In a February 23, 1897 article entitled, “Is the Zgoda a Polish Paper?”, its editors suggested their stance on Polonia’s involvement in class struggles. They wrote: “The Socialists, who call themselves Poles, are the enemies of Polish ideals.”[18]

Gender

Newspapers for Polish women also entered Chicago’s Polish newspaper scene. In 1900, the PNA’s Zgoda started publishing the weekly Zgoda: Wydania dia niewiast (“Harmony: Women’s edition”) and Zgoda: Wydania dia mężczyzn (“Harmony: Men’s edition”). The former compared with the latter, is said to have been “much less politically aggressive”, aimed at uniting immigrant women, reporting on things like “women’s rallies, recipes, home remedies and health, [and] childcare tips and tricks.”[19] Both editions ended publication in 1913. Glos Polek (“The Voice of Polish Women”), founded by the Polish Women’s Alliance in 1902, became an independently operated monthly in 1910. In its early days, the paper opposed Poles’ adoption of American cultures and values.[20] It also promoted the advancement of women through education.[21] Glos Polek continues as a monthly publication.

Explore Early Chicago Polonia through Historic Newspapers

The editorial stances of these selected newspapers surely could not represent all the ways members of Chicago Polonia made communities, nor could they capture all their interests. But they may raise some questions worthy of investigation.

To what extent were the perspectives represented by these editors shared by individual newspaper patrons? If the editorial stances of these papers do present genuine concerns of Chicago Poles at the turn of the 20th century, how did these concerns play out across space and time, in interactions with broader American society, especially in Chicago’s larger multi-ethnic community? Did the concerns of Chicago Poles change? If so, is this change reflected in the content of Polish newspapers? For instance, some of the above titles, like Zgoda and Glos Polek, began to gradually include articles in English. What might this tell us about changes in these newspapers’ audiences and their environment?

To continue exploring daily life in Chicago’s Polish community in the early 20th century and other Illinois newspapers, please visit Illinois Digital Newspaper Collections and browse newspapers by title . Or, visit Chronicling America to explore more historic Polish newspapers published in the United States.

Works Consulted:

Bekken, Jon. “Negotiating Class and Ethnicity: The Polish-Language Press in Chicago,” Polish American Studies, Vol. 57, No. 2 (Autumn, 2000), pp. 5-29.

_____ . “The Chicago Newspaper Scene: An Ecological Perspective,” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, Vol. 74, No. 3 (Autumn, 1997), pp. 490-500.

Blejwas, Stanislaus A. “Polonia and Politics,” in Polish Americans and Their History: Community, Culture, and Politics, ed. John J. Bukowczyk, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1996. pp. 121-151.

Galush, William. “Polish Americans and Religion,” in Polish Americans and Their History: Community, Culture, and Politics, ed. John J. Bukowczyk, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1996. pp. 80-92.

_____ . “Purity and Power: Chicago Polonian Feminists, 1880-1914,” Polish American Studies, Vol. 47, No. 1 (Spring, 1990), pp. 5-24.

Hardt, Hanno. “The Foreign-Language Press in American Press History,” Journal of Communication 39(2), pp. 114-131.

Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, “Dziennik Chicagoski,” https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045747/ . Accessed November 8, 2019.

_____ . “Dziennik narodowy,” https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045097/ . Accessed November 8, 2019.

_____ . “Glos Polek,” https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn79007943/ . Accessed November 8, 2019.

_____ . “Telegraf,” https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn00062200/ . Accessed November 8, 2019.

_____ . “Zgoda,” https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/2017218622/ . Accessed November 8, 2019.

_____ . “Zgoda: Wydania dia mężczyzn,” https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/2017218621/ .Accessed November 8, 2019.

_____ . “Zgoda: Wydania dal niewiast”, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/2017218620/.Accessed November 8, 2019.

Obidinski, Eugene. “The Polish American Press: Survival through Adaptation,” Polish American Studies, Vol. 34, No. 2 (Autumn, 1977), pp. 38-55.

Pacyga, Dominic A. “To Live Amongst Others: Poles and Their Neighbors in Industrial Chicago, 1865-1930,” Journal of Ethnic American History, Vol. 16, No. 1, The Poles in America (Fall, 1996), pp. 55-73.

Pula, James S. Polish Americans: An Ethnic Community. New York: Simon & Schuster Macmillan, 1995.

Vecoli, Rudolph J. “Immigration,” in The Oxford Companion to United States History. Oxford University Press, 2001. https://www-oxfordreference-com.proxy2.library.illinois.edu/ . Accessed October 28, 2019.

Zalecki, Pawel. “Poland,” in Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, ed. Thomas Riggs, 2nd ed., Vol. 4: Countries, Poland to Zimbabwe, Gale, 2015, pp. 1-8. https://go-gale-com.proxy2.library.illinois.edu/ps/start.do?p=GVRL&u=uiuc_uc . Accessed October 28, 2019.

Notes:

[1] Bekken, 2000, p. 5.; see also Twelfth Census of the United States Taken in the Year 1900, vol. 1 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1902), tables 35, 60, 24, 23, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1900/volume-1/volume-1-p13.pdf

[2] See Hardt.

[3] Bekken, 1997, p. 492.

[4] Bekken, 1997, p. 491.

[5] Bekken, 2000, pp. 6-7; see also Blejwas, p. 124.

[6] Bekken, 2000, p. 20; “Religious Indifference,” Dziennik Chicagoski, July 25, 1892.

[7] LOC, “Telegraf.”

[8] Pula, p. 33.

[9] Ibid.; Galush notes possible regional variations that paint the PNA and the PRCU as having a more cooperative relationship in some instances.

[10] Bekken, 2000, p. 20; see also Blejwas, p. 124.

[11] LOC, “Zgoda.”

[12] Bekken, 2000, p 6.

[13] LOC, “Zgoda.”

[14] LOC, “Dziennik narodowy.”

[15] Blejwas, p. 124.

[16] LOC, “Zgoda.”

[17] LOC, “Dziennik Chicagoski.”

[18] Bekken, 2000, p. 20; Dziennik Chicagoski, February 23, 1897.

[19] LOC, “Zgoda: Wydania dal niewiast.”

[20] LOC, “Glos Polek.”

[21] Ibid; see also Galush, 1990.