Where’d You Get Your Information? (Part II)

This post is the second in a set on the British band Cornershop and their obsession with information. In part two, we examine a song, “Jason Donovan / Tessa Sanderson,” about two libel cases that seem especially to have captured their imaginations:

[The first 1 minute and 4 seconds of “Jason Donovan / Tessa Sanderson,” ℗1993 Wiija Records]

Freestyle, Rhetoric

Cornershop was not concerned with information as abstraction, but as pervasive and persuasive discourse in its recorded forms, circulated by the technologies and services that, so to speak, mobilized it, put it to work, made things happen, whether desirable or undesirable. In other words, their real concern was the entire apparatus of information and its conveyance, right down to the cogs and wheels of discourse, which is to say rhetoric.1 See, for example, the anaphora, ellipsis, and polyptoton that give a two-step swing to lines like “Where do you stand? / Where do you get your information from? / Which side do you side?”2 That’s rhetoric.

Originally a branch of philosophy, rhetoric is the delivery system of information, how writers make people believe that information is true, whether or not it actually is. Rhetoric itself, as a discipline, remains indifferent to the truthfulness of information, excepting practical considerations. For example, it is often easier to make people believe true information than it is untrue information. Also, convincing people to believe untrue information might damage the writer’s character, which can make it more difficult to persuade people in the future since they might no longer trust that writer. Rhetoric is the force behind information; and make no mistake, some information can be given quite a lot of force, as I will attempt to show below.

In the song “Jason Donovan / Tessa Sanderson,” Cornershop thematized rhetoric, information, and truth by posing the interesting question, is there ever a case where successfully convincing people of the truth is actually less desirable than allowing them to continue believing information that is untrue?3 Is truth always preferable to error? To query this theme, Cornershop took the cases of Jason Donovan and Tessa Sanderson, both of whom had sued British periodicals for printing untrue and defaming information about them, which is to say libel.

What’s surprising, given the band’s general hostility towards the popular press (see Part I of this series), is that the song heaps scorn on Donovan and Sanderson, the victims of the libel, but remains silent on the periodicals guilty of those libels. There’s a lot of anger in this song:

I’m getting my head together

So I can stamp on yours

Because at bestYou remind me of Tessa Sanderson

It must be the way that you throw the javelin,

And a strong resemblance to Jason Donovan.4

Who Was Jason Donovan?

I don’t expect many American readers will be familiar with Jason Donovan—I had never heard of him before listening to the Cornershop song about him. Donovan became a famous teenage heartthrob in the 1980s, first for his role on a soap opera, then for dating another teenage celebrity (Kylie Minogue), and then as a pop star with three number one hit singles (UK).

[First thirty seconds of Jason Donovan’s “Too Many Broken Hearts” performance on Top of the Pops, Christmas Day 1989. ©1989 BBC]

After 1989 his career began to stall, as tends to happen with teenage heartthrobs, but in 1991 he landed a second, if somewhat diminished, stardom with his lead role in a West End revival of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolour Dreamcoat. Almost immediately after he premiered in this role, he became the target of an outing campaign orchestrated by a group called FROCS (Faggots Root Out Closeted Sexuality).

Outing: Kaleidoscopic Realms of Information and Rhetoric

Outing purports to reveal the truth about someone’s concealed sexuality, but in actuality it produces information, not truth. The information needn’t be supported by evidence. Probably it would be more accurate to describe outing as an allegation or accusation about someone’s sexuality. It is information launched into the world with varying levels of rhetorical force. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick best describes this rhetorical dimension in Epistemology of the Closet, published just one year before the Jason Donovan outing: “[outing] is always an intensely volatile move, depending as it does for its special surge of polemical force on the culture’s underlying phobic valuation of homosexual choice (and acquiescence in heterosexual exemption),” and elsewhere, in the same book, she so perfectly captures the frisson over such disclosures: “To the fine antennae of public attention the freshness of every drama of (especially involuntary) gay uncovering seems if anything heightened in surprise and delectability,”5 hence the insatiable appetite for such information.

The outing of Donovan lacked any evidence whatsoever, but the absence of evidence didn’t matter because, as Sedgwick argues, the closet implicates everyone: you can never definitively prove that you are not in the closet, except by coming out of the closet: a trap that can only be evaded by actually being homosexual, and by publicizing your homosexuality, and even that act only serves to tighten the snare on everyone else. What’s more, twentieth century psychology offered the tantalizing possibility that a person might not even possess full knowledge of his own sexuality: “no man must be able to ascertain that he is not (that his bonds are not) homosexual.”6 Therefore, the information that “Jason Donovan is gay” (which he wasn’t) must be accepted as information tout court. Even taken as mere information, however, it possessed no inherent value. The value of an outing lay in the uses to which it could be put.

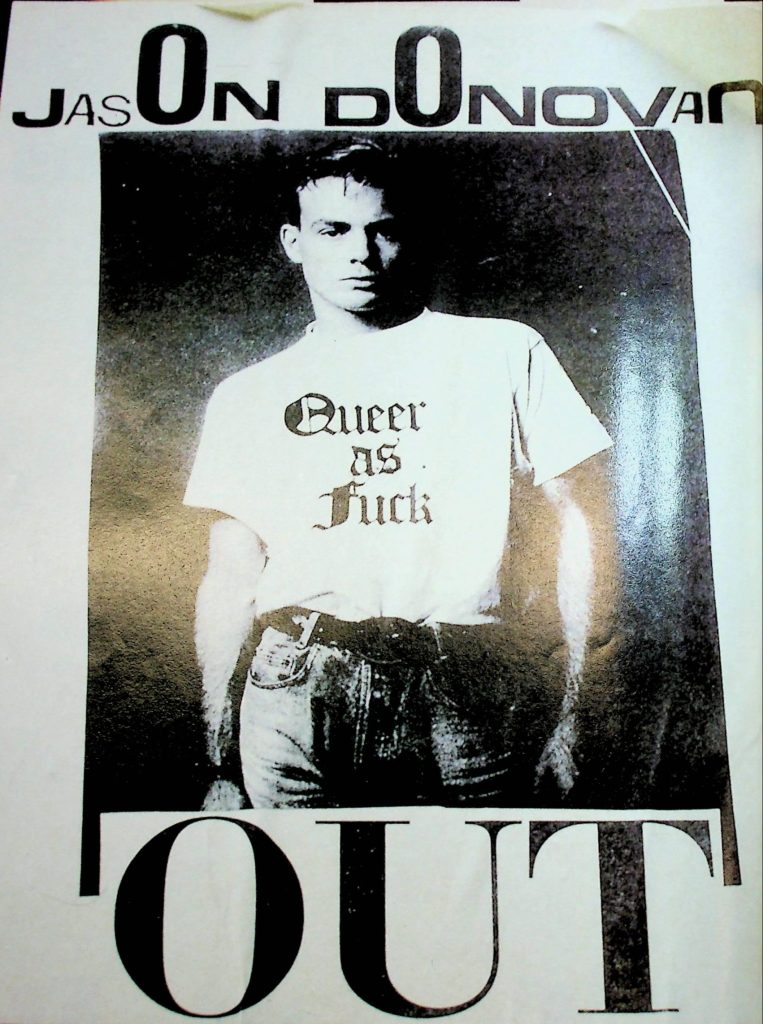

In the case of the FROCS campaign, the purpose of the information was to make homosexuality more socially acceptable; FROCS claimed to believe that outing celebrities could increase the visibility of gays in public life: if people realized just how many widely-admired men and women were gay, then they might become more accepting of homosexuality. In other words, the subjects of the outings, usually celebrities or politicians, were selected for effect-potential, which is classic (not to say classical) rhetoric. Of course, an outing can have a purely vindictive purpose as well, but FROCS denied any such intent; the nastiness of their tactics, however, belied both their denials and their claim that they merely wanted to provide positive role models for “young lesbians and gays.”7 In the case of Donovan, for example, the outing was accomplished through posters depicting him in a photoshopped t-shirt emblazoned with the words “Queer as Fuck,” which, for the early nineties, when a word like “fuck” remained pretty shocking, does not seem especially well aligned with their supposed mission (to provide positive role models for gay youth).

Whereas Donovan could have enjoyed his moment in lexical history, he instead became angry. When the Face magazine, in an article on the recent spate of celebrity outings, printed a picture of the poster, Donovan decided to sue the magazine for libel.

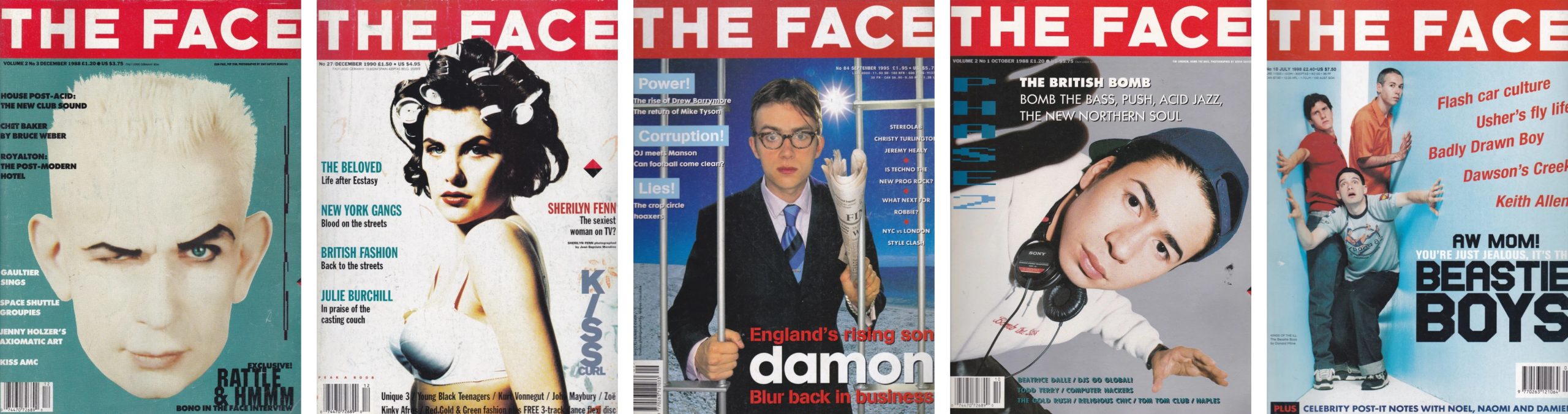

What Was the Face Magazine?

The Face magazine was a “style magazine,” a type of magazine unique at that time to Britain. Style magazines were for both men and women, and covered music, film, fashion, and culture more generally. Many consider the Face to have been the first such magazine. Benn’s Media Directory described the Face as a “Visual-oriented youth culture magazine; emphasis on music, fashion and films.” It was “a small-circulation magazine [and] the bible of youth style and culture.” For two decades (the eighties and nineties) it was the essential guide to British youth culture, widely read by taste-makers outside Britain as well. “The Face chronicled—and in some cases predicted—the twists and turns when street fashion and pop music were co-opted for individual personal expression and as forms of social and political critique.” Though not a fashion magazine, it resembled one, in its design, more than it did other magazines marketed to young adults.

Dylan Jones, editor of British GQ, described the Face as “the benchmark of all that was important in the rapidly emerging world of British and—in a heartbeat—global ‘style culture’.” Donovan himself “regularly bought the magazine to keep abreast of trends.”9 It’s difficult to think of anything like it today, in terms of its influence. At the same time, its circulation was relatively small—65,000 in 1991, compared with, for example, Fiesta, the readers’ wives magazine we examined in part one, which had a circulation of 300,000, or Smash Hits, a magazine more likely to have been read by Jason Donovan fans, which had a circulation of 555,000, or the Express, one of the tabloids that had more viciously smeared him, which sold 1,500,000 copies every single day. And yet the Face was the magazine Donovan chose to sue, a decision that, for a young British celebrity, seemed like nothing so much as career suicide.

Adjudicating Truth, Injury, and Consequences

“Libel” is a legal term: lawmakers establish the criteria defining it, and courts determine whether a specific case satisfies those criteria. Because libel is a matter of law, it differs from nation to nation. In the matter of libel, Britain is known for having weaker press protections, and a lower burden of proof, than the United States. In Britain, a libel is a published statement that is false, and “that tends to lower the plaintiff in the minds of right-thinking people.” Those are the two principal criteria. “It is also open to the plaintiff to innuendo a statement, that is, to show that a statement which is not, on the face of it, defamatory, actually has a defamatory meaning.”10 Although what really angered Donovan was the reproduction of the outing poster, his case against the magazine seems to have been largely based on this innuendo provision. Because the offending article never claimed Donovan was gay, and in fact specifically cited his denials, Donovan’s lawyers argued that the article implied he was gay, for example by describing him as “the boy with the bleached hair.”11 In other words, the jury was asked to accept that gay stereotypes were legitimate signifiers of homosexuality, and that being homosexual would be something “that tends to lower the plaintiff in the minds of right-thinking people.” Gay shaming formed the predicate for Donovan’s entire lawsuit. His lawyers characterized the supposedly-defamatory article as a gay “slur,” and this phrasing quickly caught fire in the British media: Jason Donovan had been the victim of a “gay slur.”

A Pyrrhic Victory

Donovan won his lawsuit, but found his character damaged in the process. As a Guardian interviewer put it many years later, “by trying to protect your reputation, you succeeded in destroying it.”12 (An example, by the way, of rhetorical antithesis.) The Guardian interviewer rightly noted that Donovan’s character was hurt more by his lawsuit against the Face than it ever was by the article he felt had so grievously defamed him. The tenor of the backlash can be seen, for example, in Vox magazine’s end-of-the-year readers’ poll for 1992, where Donovan was shortlisted for both “Berk of the year” (I had to look up “berk,” the meaning of which, apparently, is even more unprintable than “fuck”) as well as for “Most wildly over-rated heap of cack” (guessing you can use your fill-in-the-blank skills to infer the meaning of “cack;” otherwise I refer you to Green’s Dictionary of Slang). Musician magazine labeled him a singer “[f]or those who found Rick Astley too manly.” For his part, Donovan continued to cast himself as the victim of serial misrepresentation: “What was really disappointing was that people saw my action as a dig against homosexuality. I have no feelings against homosexuals whatsoever. However, I think I lost out through misrepresentation, because of the loss of respect from the gay community.”13 Clearly the victim of a vast, gay conspiracy.

Male Homosexual Panic

Although he was bothered by the idea that homosexual men might think him sexually available—“[Donovan] said the rumors that he was gay had made people [presumably homosexual men] ‘take a second look at me’”—he evidently had no such qualms about similar impulses from underage girls. The Guardian, which he did not sue, described him as “a lust-object […] for his barely pubescent girl fans,”14 a striking, negative example of homophobia in the progressive-leaning Guardian, since, one hopes, Donovan would find sexualized attention from a “barely pubescent girl” even more objectionable than sexualized attention from an adult male, but fear of these latter misapprehensions is entirely the point. Sedgwick, again, provides the most illuminating description, for its time (which was Donovan’s time), of how the closet affected not just gays, but all men: “So-called ‘homosexual panic’ is the most private, psychologized form in which many twentieth-century western men experience their vulnerability to the social pressure of homophobic blackmail,” which Sedgwick elsewhere labeled the “double blind” in (male) same-sex friendship,15 and which Donovan himself unwittingly described when he lamented that, because of the article, he could no longer enjoy the company of his male friends, “It’s no longer a friend or mate of mine from Australia; it is more than that.”16 In his court testimony he said that being called gay was “humiliating” and that he “took one look at [the article] and was disgusted.”17 Strong language, but consistent with Sedgwick’s account of male homosexual panic.

An Unanticipated Shift in Public Opinion?

Sedgwick argued that outing depended, “for its special surge of polemical force on the culture’s underlying phobic valuation of homosexual choice,” and we must therefore establish whether those conditions obtained in Donovan’s case. Public opinion polling might not prove “phobic valuation,” but it does reveal, even if only in broad strokes, prevailing social attitudes. Polling data also, when available as time series, have the potential to show changes in those social attitudes, and these changes might offer one explanation as to why Donovan won his lawsuit, but ultimately lost his public’s support, and possibly even why his experience of the double-bind produced so intense a response.

When Donovan sued, public attitudes towards homosexuality were beginning to change after a long decade of increasing intolerance. British polling firm Social and Community Planning Research found that, from 1983 to 1990, the percentage of respondents who considered homosexuality to be “always wrong” or “mostly wrong” held steady at well-above 60%, with the numbers hovering around 70% in the six years preceding the Face magazine article. A clear majority of respondents chose “always wrong” in every survey except 1983, a dramatic shift which the study authors attributed to the impact of AIDS on public attitudes towards the gay community.18 In 1983, 61% of respondents said that sexual relations between consenting adults of the same sex were always or mostly wrong, but by 1987 that number had spiked to 75%. 1983, the year disapproval of homosexuality began to increase again, is also the year when media coverage of AIDS began heating up, first with an episode of the BBC program Horizons, “Killer in the Village,” followed by a steady escalation in press coverage, much of it stigmatizing the disease as a “gay plague,” until 1985 when media coverage “suddenly exploded […] peaking in 1987.”19 Public opinion towards homosexuality closely tracked the media’s coverage of AIDS.

Only after 1987, when the AIDS epidemic entered what Berridge and Strong call the phase of normalization,20 did public opinion slowly begin to shift again, with a decline in the percentage of respondents who considered homosexuality to be always or mostly wrong, eventually returning to pre-AIDS epidemic levels around 1994. Even in 1995, however, a clear majority of respondents still believed homosexuality to be always or mostly wrong.

| Sexual relations between two adults of the same sex are: | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1983 | 1984 | 1985 | 1987 | 1989 | 1990 | 1993 | 1995 | |

| Always/mostly wrong | 61% | 67% | 70% | 75% | 69% | 69% | 64% | 57% |

| Not wrong at all | 17% | 16% | 13% | 11% | 14% | 14% | 19% | 21% |

| Source: British Social Attitudes, 5th report, 8th report, 19th report, and Cumulative Sourcebook. | ||||||||

Breaking those numbers down by age, you can see the shift in attitudes was especially dramatic among those respondents under the age of 30, respondents who would have been Donovan’s own contemporaries (he was 23), as well as the bulk of his fans. (Also the group most likely to have been readers of a magazine like the Face). In 1990, 49% of respondents under the age of 30 said that homosexuality is always wrong, basically unchanged since 1985. After 1990, however, the numbers began to drop quickly: 36% in 1993, 27% in 1995, and 19% in 1998, with a corresponding increase in the percentage of respondents who said that homosexuality is not wrong at all.21 Another problem for Donovan was that, although many tabloids had smeared him far more viciously, he chose instead to sue the Face, a magazine that enjoyed considerable respect and credibility among the same demographics that Donovan himself would have been courting (the magazine twice featured his ex-girlfriend, Kylie Minogue, on its cover).

At a moment of important shifts in social attitudes towards homosexuality, especially among the younger generation—a shift few could have foreseen, after a long decade of increasing fear and intolerance, fueled largely by AIDS—Donovan, with his soft bigotry, found himself on the wrong side of a historic trend line, in every sense of the word “trend.” When it became clear that his libel suit would backfire, he shifted tactics, trying impossibly to have things both ways: to be cleared of the gay slur, but also to be exonerated from the growing perception that his entire lawsuit promoted bigotry against gays. He attempted this sleight of hand by claiming that his real objection, and what he felt had truly damaged his character, was the implication that he had lied (about his sexuality): “This has not been a case about homosexuality and I resent the suggestion that it was. The [verdict] totally vindicates me and clears my name of the slur that I have lied about myself,” very likely the referent for Cornershop’s sarcastic line, “The last thing in the world I’d do to you is lie.”22

Concluding Thoughts: Which Side D’U Side?

Returning then to the question, are there ever cases where successfully convincing people of the truth is actually less desirable than allowing them to continue believing untrue information? It’s difficult to believe that, in hindsight, Donovan doesn’t wish he had just let the FROCS campaign run its course. Cornershop ask, “Where d’you stand?” and “Which side d’you side?” These are questions, to them, as important as “Where d’you get your information?” Coming hot off the heels of a decade when AIDS was widely dubbed a “gay plague,” the fear of gays, especially gay males, would be difficult to overstate. Thinking back to 1991, I find it stretches credulity not to see Donovan’s “disgust” as anything but a fear of being numbered among these social pariahs.

A sad irony in all this hullabaloo was that Donovan’s failing career had been saved by his performance in a West End musical (Joseph and the Amazing Technicolour Dreamcoat). The musical even gave him his first hit single in over two years. The deep connections between musical theater and gay male subcultures have been well-documented, and Donovan’s performance was enthusiastically received by gays: “Thousands of gay men in the capital’s pubs and clubs are singing along to his latest technicolour single: ‘As teenage girls all sit there screaming / Our Jason’s dreaming / Any queen will do’.”23 Donovan burned through a lot of goodwill with his lawsuit, and what he really achieved by successfully scotching some rumors being spread by posters pasted on Covent Garden alley walls…only Jason Donovan will ever know that part.

A Word on Sources from the Readers’ Advisory Bureau

Many of the publications that trafficked in the kind of tawdry, speculative gossip treated in this blog post were not collected by our library. Of particular interest for this post would have been the giants of Britain’s thriving tabloid industry, the Express, the Sun, and the Mirror, none of which we have here for 1991. We do, fortunately, have the Daily Mail online, through Gale, and that is an indispensable source of information on British popular culture of the 1990s. The Guardian (in ProQuest Historical Newspapers) also provided a wealth of information, but being a more respectable newspaper than the Daily Mail it lacked that “in the gutter” perspective I was able to find in the Daily Mail.

The Face magazine is another important publication not available here, and also not indexed anywhere, so even accessing articles through interlibrary loan was a challenge; I relied on my own personal collection to fill gaps. The ProQuest digital collection Entertainment Industry Magazine Archive has a strong selection of British music magazines, including Vox. This collection originally included NME and Melody Maker, which would have been superb sources, but the contents of these licensed electronic resources often change without notice.

For interpreting some of the slang in British youth magazines, I cannot recommend Green’s Dictionary of Slang highly enough, and it’s available online through Oxford Reference.

Epistemology of the Closet and Between Men, both by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, seem to me to be indispensable for exploring this topic, not just because they are contemporary documents, but also because she is one of the few theorists to examine the effect of the closet on men who do not identify as homosexual.

The LGBT Magazine Archive includes the Pink Paper, which was the only national gay newspaper in Britain in 1991; Ben Summerskill, who wrote the offending Face magazine article, was the Associate Editor of the Pink Paper.

For British public opinion of the 1990s, the British Social Attitudes series is recommended.

To learn more about rhetoric, the best book is Classical Rhetoric for the Modern Student. It’s actually a textbook, but is a pleasure to read.

Notes

1. That discipline much-maligned for its supposed trivial pedanticism—Samuel Johnson’s famous ridicule being more-or-less general, “[A]ll a Rhetoricians Rules / Teach nothing but to name his Tools.”Hudibras, ed. John Wilders (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967), 4.

2. Cornershop, “Where D’U Get Your Information,” Hold on It Hurts (London: Wiiija Records, 1993).

3. Untrue or false information is now more usually called “misinformation” or “disinformation,” which I consider antonymic mirages, seeming to suggest that “information” is true, or should be true, or makes some implicit claim to truth. Certainly rhetoric as a discipline concerns itself with truth, and provides the rhetorician with deeply elaborated methods (logic) for demonstrating the truth of an argument, but it must be remembered that these methods compose only one of three modes of persuasion available to the rhetorician, the other two modes being by no means specifically oriented towards truth. Regarding the song “Jason Donovan / Tessa Sanderson,” it should be noted that the song treats other themes of special interest to Cornershop, including immigration, sexism, classism, homophobia, and racism.

4. Cornershop, “Jason Donovan / Tessa Sanderson.”

5. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Epistemology of the Closet (Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 1990), 245 and 67.

6. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), 88-89. Thirty years later there is still no evidence that Donovan is or was or even might-have-been gay.

7. “Any Queen Will Do,” Pink Paper (London), July 13, 1991, 1. FROCS was a shadowy organization that might or might-not have been responsible for the Donovan poster. See “All Sweet and Innocent, Shane and Simon: FROCS Was ‘Only Hoaxing’,” Capital Gay (London), August 2, 1991, 1. Even the most generous possible interpretation of FROCS‘s motives must acknowledge that it rested on shakey intellectual grounds: as many theorists had already argued by 1991, every act of outing, or coming out, merely reproduces the very closet the outing seeks to abolish. See Sedgwick, Epistemology, 71-72.

8. See “Copenhagen Welcomes Euro-Gays,” Capital Gay (London), January 11, 1991, 15: “The only real note of discord came when OutRage’s representative walked out of the conference in outraged protest at the sale of T-shirts bearing the slogan ‘Queer as Fuck.’ In a letter of explanation, he said that the use of the term ‘queer’ was so self-oppressive that he felt he must leave. Since the shirts themselves were produced by Outrage this caused some confusion.” See also Nick Cohen, “Secret World of ‘Outing’ Group That Seeks Publicity for Others,” Independent (London), July 30, 1991, 3: “To the vast majority of homosexual men, queer is a term of moronic abuse. Michael Cashman, chairman of Stonewall, a gay pressure group which quietly works for legal reform, said that the word showed society’s failure to understand ‘that there is no such thing as a separate homosexual community; that gay men’s lives can be as ordinary, dull or exciting as anyone else’s.”

9. Benn’s Media Directory (1991), s.v. “Face.” Sarah Boseley, “Expensive Outing Could Smother the Face: Jason Donovan’s Supporters Were Determined on a Public Battle to Nail the Lie of His Alleged Homosexuality in the Media,” Guardian, April 4, 1992, 3. For Dylan Jones on the Face, see his foreword to Paul Gorman, The Story of the Face: The Magazine That Changed Culture (London: Thames and Hudson, 2017), 6.; and Bill Mouland, “My Disgust at This Gay Slur,” Daily Mail (London), March 31, 1992, 5.

10. William J. Stewart, Collins Dictionary of Law, 3rd ed. (Glasgow: Collins, 2006).

11. Ben Summerskill, “Forced Out,” Face, August 1991, 72.

12. Hannah Pool, “Jason Donovan,” Guardian (London), October 4, 2007, 21.

13. “VOX Readers’ Poll Results,” Vox, February 1, 1993, 31.; Jonathon Green, “Berk,” in Green’s Dictionary of Slang (Chambers Harrap Publishers, 2011).; J.D. Considine, “Backside: J.D’.s Golden Decade,” Musician, August 1, 1992, 91.; and Mal Peachey, “Jason Donovan,” Vox, 1993, 5.

14. Bill Mouland, “Court Giggles over Jason, the Amazing Lemon Blond,” Daily Mail (London), April 1, 1992, 5; and Sarah Boseley, “Expensive Outing,” 3.

15. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Between Men, 89.

16. Bill Mouland, “Court Giggles.”

17. Bill Mouland, “My Disgust at This Gay Slur,” 5.

18. Lindsay Brook and Social and Community Planning Research, British Social Attitudes Cumulative Sourcebook: The First Six Surveys (Aldershot, Hants, England ; Gower, 1992), M.1-3.

19. Raphaela van Oers, “Stigma, Prejudice, and Sympathy: British Press Coverage of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s,” (master’s thesis, McGill University, 2022), 15.

20. “In the new phase which began around 1988, AIDS has begun to be perceived more as a ‘normal’ non-epidemic chronic disease, and reactions to it have become professionalized and institutionalized,” Virginia Berridge and Philip Strong, “AIDS in the UK: Contemporary History and the Study of Policy,” Twentieth Century British History 2, no. 2 (April 1991): 154, 166.

21. Alison Park and National Centre for Social Research, British Social Attitudes. The 19th Report, British Social Attitudes Survey Series 19 (London: SAGE, 2002).

22. Bill Mouland, “Jason’s Mercy for Gay Slur Magazine,” Daily Mail, April 4, 1992, 3; and Cornershop, “Jason Donovan / Tessa Sanderson.”

23. Sarah Boseley, “Editor ‘Cut Libel’ from Outing Story’,” Guardian (London), April 2, 1992, 2. For more on Donovan’s enthusiastic reception as Joseph among London gays, see “Editor ‘Trying to Help Jason’,” Daily Mail (London), April 2, 1992, 5. For more on the connections between gay male subcultures and musical theater, see John M. Clum, Something for the Boys: Musical Theater and Gay Culture (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999).