Letter from 1993, with Unexplained Anachronisms

Tjinder Singh and his post-punk band Cornershop really, really care about information—its technologies, its media, its creators, its consumers—which, for the 1990s at least, is a little unusual. Why care about anything at all when punk has bequeathed them a license to lunge pell-mell down the abyss of heedless anger, smashing up everything and replacing it with nothing? Possibly because so much of Singh’s music is about the bigotry of everyday life in England, and anger alone seems an inadequate response. Bigotry must be granted no quarter: “There’s racists, sexists, homophobics; fight the powers that be!”1

Punk, in contrast, for all its sound and fury, discursively negated itself, ultimately signifying nothing. The true legacy of punk rock became visible as its DNA unraveled (ca. 1979), exposing a mess of internal contradictions, some of them quite nasty:

- reaction / decadence

- right-wing / left-wing

- frenzy / sedation

- populism / elitism

- obscurity / celebrity

- working class / middle class

- DIY / EMI

- racism / liberalism

- streetwear / haute couture

- Sid Vicious / Vivienne Westwood

Which isn’t to say that Singh has not been influenced by punk, because he obviously has, but it’s difficult to imagine how he could fully embrace an ethos riddled with so much terminal conflict. As the son of Sikh immigrants in 1980s England, racism was his daily reality: “[racism] was always there, in the air, from being chased by motorbikes to being beaten up just for the sake of it. It was always there.”2 Even the most generous possible view of punk must concede it is, in many respects, a form of white privilege, a lifestyle choice to which political radicalism is accessory (like a pair of Doc Martens) rather than essential, the best single piece of evidence for which is, ironically, the seminal Clash song, “White Riot:”

White riot,

I wanna riot;

White riot,

I wanna riot of my own.Black man got a lot of problems,

But he don’t mind throwing a brick;

White people go to school

Where they teach you how to be thick.3

This chorus is the tantrum of a spoiled child, covetous even to the point of coveting his black neighbor’s oppression, “I wanna riot of my own,” while the verse’s tetrameter (I think we have iambics here) will not scan—it all sounds awkward, to my ear anyway, giving one of punk’s most famous songs a gawky, sophomoric dilettantism, or would have anyway had the song not been widely and fantastically misinterpreted as a neo-Nazi anthem. That so few could fathom any other interpretation does, it seems, point towards an embarrassing truth, that punk was something of a lifestyle choice: if the punks weren’t neo-Nazis, then what on earth were they so exercised over? The misinterpretation also eerily reinforced punk’s many connections with (and disconnections from) white supremacist movements.

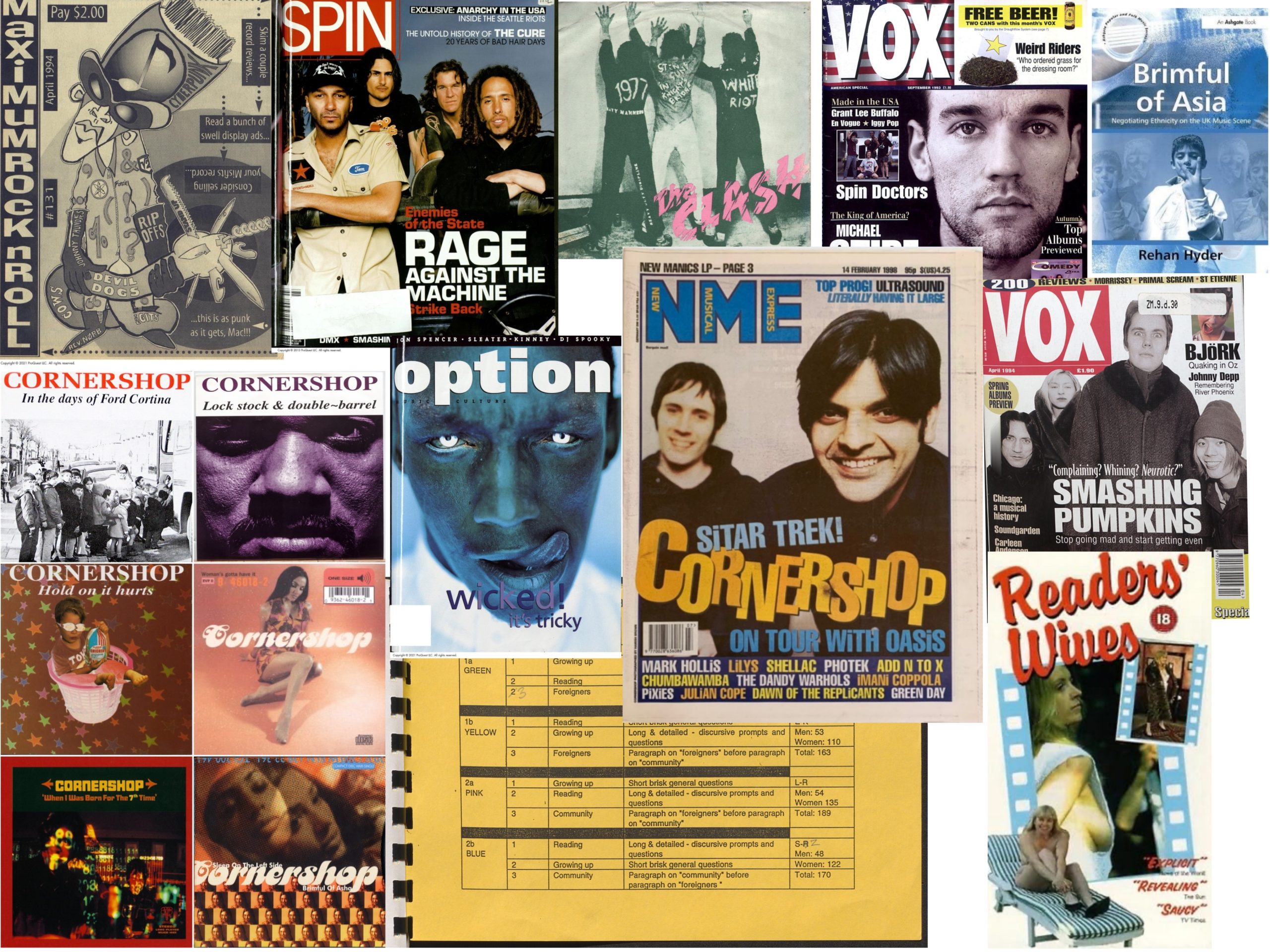

So while the anger and energy of punk must surely appeal to Singh emotionally, it would be surprising if he didn’t feel that the subjects of his songs call for more than the punk idiom can supply; if nothing else these subjects call for intellectual clarity, something quite beyond the limited and limiting capacities of punk’s ideological ambivalence. Even documenting his experiences of bigotry seems to interest Singh less than agitating for real change (the song “Change” is—you guessed it—all about the need for social change). Singh’s approach to songwriting must be influenced by his sense of being an outsider, a foreigner or alien, in Britain, a subject about which he has been quite open. The song “England’s Dreaming” begins with a sample from what seems to be a science fiction film: “People, we finally have to fight. We don’t want to, but the people of Earth leave us no choice.”4 At the same time, in interviews at least, he never seems entirely comfortable in the agitator role he has assumed; he embraces and then suddenly eschews its mantle.5 His early songs, however, belie that hesitance, and are fervently political. Critics generally regard Cornershop’s debut E.P., In the Days of Ford Cortina, as a call-to-arms, four-track masterpiece of early-nineties agit-punk.

Singh’s breakthrough has been in recognizing that you can’t be effectively political without reliable information, and here he jumps leaps and bounds ahead of his contemporaries. One of his final punk-inflected songs cannily targets punk’s failure in this regard: “Clear all data, call all destroyer / Clear all data, call all destroyer.”6 I have never before encountered a rock band so singularly preoccupied with a subject like information. Cornershop’s world is filled with information, and people are like sponges absorbing it.

The most remarkable example of this preoccupation is their song “Where D’U Get Your Information,” the centerpiece of which is a fevered, hectoring chorus that simultaneously questions, challenges, and denounces, with knuckles-down vociferation:

Where d’u get your information

Where d’u get your information

Where d’u get your information

Where d’u get your information.7

Not so impressive on the page, perhaps (I can better picture it spray-painted on a brick wall), but it sounds like sonic retribution, buzzing low-fi guitars that lurch and spark like downed power lines in a pool of rhythm section and vocals, shimmering depths of drama. Experience for yourself:

[The first 1 minute and 20 seconds of “Where D’U Get Your Information,” ℗1993 Wiija Records]

The chorus breaks upon you like a pulse thunderstorm, and makes me feel blindfolded-and-bound-to-a-wooden-chair like a political-prisoner-under-interrogation. Clearly, for Singh, the source of your information reveals something about your character. The song continues, sarcastically, “& by the time we pull into Stockport / Well you’re well informed in serial form,” referring to the newsstand trash of working-class Lancashire, and to the readers whose opinions are synchronously serialized like ticker tape marching lockstep from a telegraph machine (/ Or Stormtroopers boarding transport ships in Attack of the Clones, final scene). And, of course, Singh named his band after the corner shops and newsstands where newspapers and magazines are displayed in dizzying density alongside comic books, lottery tickets, paperback novels, phone cards, postcards, street maps, and more. (For the reason Singh named his band Cornershop, see endnote 2):

Rarely does Singh write about information in the abstract, possibly because the subjects of his songs are anything but abstract to him: for Singh, racism is not an idea, but the experience of, for example, “being chased by motorbikes [and] being beaten up.” When under attack, your whole world suddenly contracts to what is immediate and concrete, and that’s something I remember noticing when I first began listening to Cornershop, how concrete and specific their songs are, almost as though abstraction were a tool of bourgeois mystification, and in some ways it is, though in Cornershop’s case it might be more precise to call it a tool of white mystification. Abstraction too often enables us to ignore what is actually happening right in front of our eyes, “What is happening in London, in Europe, in Spain, in France, in Russia,”10 in other words, reality.

Let me give an example of this mystification, from the Mass Observation archive. (Mass Observation is a University of Sussex research project that asks “mass observers” to record factual information about their daily lives, as well as more subjective responses to questions about society.) The Spring, 1993 directive includes the following question about “foreigners:”

Are there any people in the locality where you live that are thought of as ‘foreigners’? What makes them ‘foreign’? For example, is it the length of time they have lived there, accent, appearance, life style? What do people who move into your locality have to do to be ‘accepted’?

One respondent, a white, middle-class woman living in Stafford, a community about half an hour from Wolverhampton (where Singh grew up, in England’s Birmingham-anchored Midlands), submitted the following response:

Hence the urgency of the question, “Where d’u get your information?” And the reason it demands a concrete answer. In a Cornershop song, that answer is likely to be a technology or service through which information is created, recorded, or disseminated: radios, televisions, books, cinemas, cameras, recipes, public address systems, letters, movie studios, conversations, computers, telephones, posters, juke boxes, newspapers, magazines, shopping lists, record players, public libraries, the postal service, and so forth.

Singh is also interested in the way information and information technology dehumanize, to the point where humans sometimes begin to resemble information technology itself: “I want you each and all to switch your tiny mind on / I want you each and all to switch your tiny mind / I want you each and all to switch your tiny mind on.”12 In the song “Readers’ Wives” (a model of compressed mordancy), people are as degraded as the information they consume:

Yes we’re showing everything & showing nothing

Giving everything & getting nothing

Showing everything & showing nothing

Giving everything and getting nothing in return

All our lives are like Readers’ Wives

All our lives are just like Readers’ Wives.13

The title of the song refers to smut rags that publish reader-submitted pornographic photographs of their wives. A readers’ wives magazine pays up to £20 for a photograph it chooses to publish, but these magazines make millions off the sales and advertising. The editor of the most successful readers’ wives magazine, Fiesta, argues that readers’ wives magazines flourish in the absence of free and open exchange of information about sex:

[Excerpt from the documentary Readers’ Wives, ©1994 Channel Four Television Corporation.]

He seems to be arguing that an information vacuum will quickly be filled with trash: “If there was an open and free attitude to sexual discussion then there would be no [readers’ wives magazines].”14 Which brings us back to Cornershop, and Singh’s point that an absence of reliable information makes possible these social distortions and dissociations, such as a disbelief in racism, or a belief that the value of your own sexual exploitation is about twenty quid (if you’re lucky).

The song is also a reminder of how media often replace our own direct experiences of reality. A lot of British men, it seems, enjoy their wives more in the pages of a magazine than they do in reality. This usurpation of reality, or at least the desperate hope that media will do so, can be seen in an unsettling interview, from the same documentary, with a reader’s wife model, who is a rape survivor, and who feels that, by appearing in the magazine, she has finally emerged from the shell she entered after her rape, and also that by appearing in the magazine she can prevent other women from being raped, because she believes that the sex men see in the magazine will substitute for the sex they would otherwise obtain through assaulting women, that the magazine will prove more satisfying than reality.15

[Excerpt from the documentary Readers’ Wives, ©1994 Channel Four Television Corporation.]

Information technologies (newspapers and magazines are, yes, technologies) confer upon information an appeal and a force that direct experience (reality?) can barely counter, as in the case of the Stafford woman who sees the defensive barriers around the Sikh temple while simultaneously seeing little racism in her community. Singh parodies this dissonance in the lines “Heard it on the crystal / Saw it on T.V. / That Peter Singh / Is Elvis Aaron Presley,”16 the joke being that Peter Singh (no relation to Tjinder), a popular Elvis impersonator, looks nothing at all like Elvis, but that some people (“Some people / Well they’re too thick to understand”17) will always believe what they hear on the radio or see on the television. These lines anticipate what young people will be saying in ten years, “I read it on the Internet,” that sad, because so naïve, invocation of the Internet as some ironclad guarantor of truth, which will become for teachers a doctrinal error to be rooted out more relentlessly even than split infinitives, fused sentences, misplaced modifiers, faulty subordination, mixed metaphors, comma splices, dangling participles, sentence fragments…all the fractures, contusions, sprains, and abrasions of freshman English compositions everywhere.

To be continued on the semester’s flipside, December 1st, see you in the future!

Where I Got My Information, and a Few Additional Comments

1. Cornershop, “England’s Dreaming,” Lock Stock & Double-Barrel (London: Wiiija Records, 1993), EP; Mal Peachy, “Cornershop: Elvis Sex-Change,” Vox, 74.

2. Singh quote from an interview with Larry Kanter in “Cornershop’s Punjabi Rock,” Option, September/October, 1996, 45; Even the name Singh chose for his band, Cornershop, is a reference to the racist joke that corner shop convenience stores are usually run by Indians, Craig McLean, “The Politics of Dancing,” Spin, March, 2000, 121. The corollary in the United States would be racist jokes like the one made by Joe Biden when he said that a person cannot go to a Dunkin’ Donuts or a 7-Eleven “unless you have a slight Indian accent.” See Adam Nagourney, “Biden Unwraps His Bid for ’08 With an Oops,” New York Times, February 1, 2007, A20. For more on the ambivalent relationship, in Britain, between youth of Indian descent and punk rock sub-cultures, see Rehan Hyder, Brimful of Asia: Negotiating Ethnicity on the UK Music Scene (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004), 162. For more on punk rock and white nationalist movements, see Gerfried Ambrosch, “Guilty of Being White: Punk’s Ambivalent Relationship with Race and Racism,” Journal of Popular Culture 51, no. 4 (2018): 902-922.

3. The Clash, “White Riot,” The Clash (London: CBS Records, 1977), LP.

4. Cornershop, “England’s Dreaming.”

5. Andy Chapman, “Cornershop,” Maximum Rocknroll, April, 1994, 80-81.

6. Cornershop, “Call All Destroyer,” Woman’s Gotta Have It (New York: Luka Bop, 1995), CD.

7. Cornershop, “Where D’U Get Your Information,” Hold on It Hurts (London: Wiiija Records, 1993), CD.

8. Craig McLean, “Cornershop: Hold on It Hurts,” Vox, April, 1994, 66.

9. “Sleep on the Left Side,” and “Brimful of Asha,” When I Was Born for the Seventh Time (London: Wiiija Records, 1997), CD.

10. Cornershop, “What Is Happening,” When I Was Born for the Seventh Time.

11. Mass Observation Project L1691, “1993 Spring Directive Part 3: Foreigners,” SxMOA2/1/39/3/1/181, 1.

12. Cornershop, “Good Shit,” When I Was Born for the Seventh Time.

13. Cornershop, “Readers’ Wives,” Hold on It Hurts.

14. Excerpt from an interview with Ross Gilfillan, editor-in-chief of Galaxie Publications, publisher of the first and most successful readers’ wives magazine, Fiesta, in the documentary Readers’ Wives, directed by Susanna White (London: Channel Four Television Corporation, 1994), VHS. Transcript (supplied by blog author): “If British society wasn’t so hung-up, if it wasn’t so—, if it didn’t have to talk about sex in hushed tones and innuendo, the nudge-nudge syndrome, then we wouldn’t be able to publish. If there was an open and free attitude to sexual discussion then there would be no Fiesta, so what we really exploit is society’s attitude to sex, British society.”

14. Excerpt from an interview with Lydia of Cheshire, one of the readers’ wives in the documentary Readers’ Wives, directed by Susanna White.

16. Cornershop, “Skin,” Hold on It Hurts. Peter Singh looks nothing like Elvis, but, in my experience at least, neither do most Elvis impersonators.

17. Cornershop, “Call All Destroyer.”

The New Pictorial Review of Information Sources

Readers’ Advisory Service

For more information on Cornershop, the best place to begin is their music. My favorite Cornershop CD is Woman’s Gotta Have It, but their most famous, and most acclaimed, is When I Was Born for the Seventh Time. Cornershop creates a new musical universe with every album: I think In the Days of Ford Cortina splendid, especially considering its low-fi production values.

On punk rock, I recommend England’s Dreaming: Anarchy, Sex Pistols, Punk Rock, and Beyond (London: Faber & Faber, 1991) by Jon Savage. It has been reprinted about a hundred times (literally), most recently in 2021.