The Baby Boomers hit the U of I campus like an earthquake. Their sheer numbers forced University administrators to build additional facilities and to enlarge the campus, creating the “Big U” that we have today. Their intense activism ushered in a set of sweeping changes that redefined the role of students on campus. The state and federal governments invested heavily in the University, bolstering the Graduate School and making the U of I one of the top research institutions in the country. Questions about the proper balance between research and teaching began to be asked. The University would never be the same.

Quad Day Alumni & Administrator Oral History

![]()

Administration

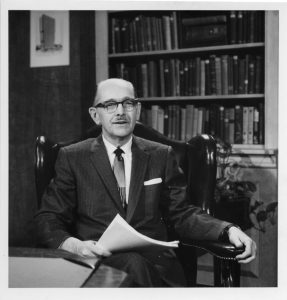

When Lloyd Morey became acting president in 1954, the numbers of college students nationwide exploded and implications of the post-war baby boom were becoming apparent. Morey knew the campus could never handle the expected increase in enrollment. He therefore endorsed a 1954 plan to expand the Urbana campus and create a new Chicago campus.

His successor, David Dodds Henry, oversaw the plan, campaigning successfully for a massive state bond issue that eventually funded the Chicago campus, which opened in 1965, and several major Urbana campus buildings.

By the late 1960s, a new governor clamped down on university spending. Declining state support, said new President John Corbally in 1971, left the University fighting for its very financial survival.

During the two-year-long administration of Acting President Lloyd Morey, University officials began to prepare for the coming of the Baby Boomers. It was a familiar story: how to cope with an expanding enrollment. But the magnitude of the post-war Baby Boom was anything but ordinary. In the state of Illinois 141,056 babies had been born in 1945; a year later that figure increased to 177,607 and by 1951 had jumped to 202,845. Adding to the problem, the number of high school students choosing to go on to college was exploding, growing from only fifteen percent in 1940 to forty percent in 1955.[1] This “avalanche of children” threatened to overwhelm an already overcrowded University.

In the summer of 1954 a faculty committee estimated that enrollment on the Urbana-Champaign campus would reach 23,000 in 1962-63 and a whopping 38,000 by 1972. (Enrollment on the UIUC campus in the winter session of 1953-4 was only 17,652.) The committee recommended the construction of additional facilities to address both current overcrowding and the future enrollment boom. It also made a case for the establishment of a four-year U of I campus in the Chicago area with the argument that half of the University’s students and half of the state’s population lived in Cook and the surrounding counties.[2]

Acting President Morey was fully on board with these recommendations. He set the wheels in motion for the creation of a Chicago campus and prodded Urbana campus planners to get going on an ambitious building program. Morey wanted University officials to start thinking in the longer term regarding campus planning and development.[3]

Planning was critical to Morey’s successor, David Dodds Henry, the former executive vice chancellor of New York University. A onetime president of Wayne State University and the owner of three degrees from Penn State, the 49-year-old Henry—a slight man with a thin mustache and thick glasses–had a reputation as one of the ablest educational administrators in the nation. Not long after taking office on September 1, 1955, Henry realized the urgent need for “extensive planning.” “Although the University was on (an) even keel, its management in good order, its structure sound and well manned, it was not ready for the changes that I felt were coming,” he wrote in his memoir.[4]

Perhaps the biggest change coming down the pike was of course the approaching “tidal wave of students.” And the University was not at all prepared for the invasion of Baby Boomers. “The Urbana campus had had little, relatively limited capital expenditure in the previous two decades,” Henry noted. “There was great need for updating facilities.”[5] Indeed, the University suffered from a severe space deficit: in the years of depression and war, the U of I had received little money for buildings, and even in the booming post-war years, added building space failed to keep pace with the growing enrollment.[6]

The need was there, but where was the money to come from to finance all of these new buildings? Acting upon an idea of Illinois Governor William Grant Stratton, the state’s universities campaigned for a massive bond issue to meet their capital needs.[7] Voters rejected the bond issue in 1958 but two years later they approved a slightly smaller one.[8] The University received the lion’s share of the proceeds from the bond issue–$98 million. Of that amount, $50 million was earmarked for the building of the Chicago campus (which opened in 1965), with the remainder going to Urbana-Champaign.[9] The passage of the bond issue proved to be a watershed event in the history of the U of I. “In retrospect,” Henry asserted, “it can be said that had the bond issue not succeeded, the Chicago development would not have been possible in the time frame that later occurred. The Urbana campus could not have accepted the large enrollments that the new buildings made possible.”[10] Some of these new buildings made possible by the bond issue included Commerce West (Wohlers Hall), the Education

According to President Henry, “the outstanding characteristic” of his administration was “growth—growth in enrollment, in facilities, in number of programs, in quality and scope of educational achievement.”[11] Between 1959 and 1970, the University’s Urbana-Champaign campus experienced record enrollments twelve years in a row, jumping from 20,219 to 34,018 students.[12]

The number of dormitory units tripled, and the value of the University’s physical plant quadrupled, going from $128,145,805 in 1955 to $625,837,223 in 1971.[13] State operating appropriations went from $87 million in 1955-57 to $268 million in 1967-69.[14] Federal funds provided nearly 90% of the income for University research; in 1967 the U of I was the third largest university recipient of federal funds behind only the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of Michigan.[15] Bolstered by this federal money, the Graduate School flourished, with its biology, physical sciences, and engineering programs ranking among the nation’s best.[16] As a means of coping with this rampant growth, the University was reorganized in 1966 into Urbana-Champaign, Chicago Circle, and Medical Center campuses under chancellors.[17]

The last years of the Henry administration were marked by campus unrest. Like their counterparts on dozens of other American campuses, thousands of U of I students took to the streets to protest University regulations, censorship, the Vietnam War, recruitment by military contractors, and racial and sexual discrimination in their many forms. As with the landmark periods of the Burrill and Chase administrations, the era of the late-1960s and early-1970s transformed campus life in profound ways. Administrators here and elsewhere responded to the turbulent times by giving undergraduates an unprecedented degree of latitude in running their lives, overturning the long-standing policy of in loco parentis.[18]

By the late 1960s, the boom years were coming to an end, and campus development ground to a halt, literally. In early 1969 the newly elected Governor Richard Ogilvie imposed a freeze on campus construction after surveying the state’s sorry finances.[19] During his four years in office, Ogilvie continued to take a hard line against University spending. Adding to the University’s woes, the combative Illinois Board of Higher Education—created in the early 1960s to oversee the state’s universities—often sided with the governor on budgetary matters.[20] By 1971, there were four new state universities—Chicago State, Governor’s State, Northeastern Illinois, and Sangamon State—as well as a slew of new junior colleges competing with the University of Illinois and the other five state schools for a share of a diminishing pot of state money.[21] Times certainly had changed: In 1948 a whopping 78 percent of the state’s tax dollars devoted to higher education had gone to the U of I; by 1968, that figure had fallen to 49 percent.[22]

President John Corbally, Henry’s successor, faced a grim environment when he entered office in September 1971. Morale was down, budgets were down, and even enrollments were down for the first time in over a decade. The University was fighting for its very financial survival, Corbally, the former president and chancellor of Syracuse University, declared in January 1972. “Our task is to run as fast and as hard as we can to stand still—to avoid losing ground,” he said.[23] Trapped in “a rapidly-closing vise of falling enrollment, stringent budgets, and declining support from the state and federal governments,” Corbally hoped to achieve cost savings through administrative reform and reorganization.[24] Tuition was also hiked, increasing from $85 per semester for in-state students in 1968-69 to $317 by the end of the 1970s.[25] After eight years of frustration, Corbally retired from the U of I presidency in the fall of 1979, explaining that he felt “an increasing sense of repetitiousness in the tasks of my position.”[26] Corbally was succeeded by Stanley O. Ikenberry, who, at age 44, became the University’s youngest-ever president. Ikenberry would bring new vitality to the job.

References

[1]Daily Illini, 3 November 1960.

[2]Ibid., 16 July 1954.

[3]Ibid., 13 May 1955.

[4]David Henry, “Career Highlights and Some Sidelights,” unpublished MS, 1983, 140, David Henry Papers (2/12/20), B: 25, F: Memoirs, University of Illinois Archives.

[5]Ibid., 141.

[6]Daily Illini, 1 August 1960.

[7]Ibid., 27 November 1956.

[8]Henry, 162.

[9]Daily Illini, 6 July 1961.

[10]Henry, 163.

[11]Ibid., 329.

[12]Daily Illini, 18 November 1959; 3 December 1970.

[13]Henry, 164.

[14]Report No. 31 of the Executive Director, State of Illinois Board of Higher Education, 23 November 1964, Dean of Students General Correspondence (41/1/1), B: 44, F: Henry, University of Illinois Archives; Daily Illini, 11 May 1967.

[15]Daily Illini, 17 April 1969.

[16]Ibid., 24 May 1966.

[17]Henry, 249.

[18]Daily Illini, 16 February 1977.

[19]Ibid., 7 February 1969.

[20]Ibid., 21 March 1972.

[21]Ibid., 13 February 1971.

[22]Maynard Brichford, “Brief History of the University of Illinois,” University of Illinois Archives Blog.

[23]Daily Illini, 21 January 1972.

[24]Ibid., 5 April 1974.

[25]Ibid., 22 July 1975.

[26]Board of Trustees Minutes, 20 September 1978, 78-79.

![]()

Academics

When new President David Henry arrived in 1955, the University was considered an “open admissions” school with low academic standards. Within 10 years, the University’s standards tightened to the point that it became known as an elite institution.

Henry also decided to focus the institution on its strong suits of graduate and professional education, and research. By the time he left in 1971, the U of I awarded the second-highest number of PhDs in science and engineering. By the time of Henry’s successor, John Corbally, however, enrollments and budgets were falling. To stave off financial ruin, Corbally tried, but generally failed, to cut “unnecessary” academic programs.

David Henry assumed the U of I presidency in the fall of 1955, the University, he claimed, had a reputation as an “‘open admissions’ institution with low academic standards, a place where superior students were not attracted.” Under Henry, admissions standards were tightened and the University gained a reputation as a highly selective, even elite, institution.[1] Marking a watershed of sorts, in 1964 over 9,000 qualified applicants were denied admission to the University.[2] John Corbally, Henry’s successor, endorsed “limited access” and celebrated the U of I’s new-found elite status. “The greatest P-R program with the greatest readership is made up of rejection slips to qualified students who can’t get in,” Corbally said in 1976.[3]

President Henry came to believe that the University could no longer “be all things to all people.” Undergraduate enrollment would have to be shared more widely with the state’s regional universities and junior colleges, and the University would focus on the academic roles “it could do best and for which it was uniquely and pre-eminently qualified”—in particular graduate and professional education and research.[4] Near the end of Henry’s tenure, there were nearly 7,500 graduate students on the Urbana-Champaign campus, and the University was receiving over $63 million in federal support for educational and research programs—the third largest university recipient of federal funds behind the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of Michigan.[5]

The Graduate School came into its own during this period. In fiscal year 1967, Illinois awarded more PhDs in science and engineering than any other school in the nation except the University of California, Berkeley.[6] The previous year, an American Council on Education survey of graduate education gave distinguished marks to Illinois in biological science, physical science, and engineering—marks that placed the U of I among the nation’s top ten graduate schools in those fields.[7] According to a National Academy of Science report, between 1960 and 1966, Illinois ranked third in the nation as a producer of undergraduates who went on to earn doctorates.[8]

Academic freedom became a major issue during the Henry administration. In March 1960 Leo Koch, an assistant professor of biological sciences, sparked a long-lasting controversy when he wrote a letter to the Daily Illini condoning pre-marital sex. “With modern contraceptives and medical advice readily available at the nearest drugstore, or at least a family physician, there is no valid reason why sexual intercourse should not be condoned among those sufficiently mature to engage in it without social consequences and without violating their own codes of morality and ethics,” Koch declared in the letter.[9] Acting upon the recommendation of the executive committee of LAS, President Henry fired Koch for “a grave breach of academic responsibility.” “The views expressed,” Henry said, “are offensive and repugnant, contrary to commonly accepted standards of morality.”[10] Despite protests from groups arguing for academic freedom, the board of trustees upheld Koch’s dismissal and the Illinois and the United States Supreme Court refused to intervene in the matter. In 1963 the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) voted to censure the U of I after an AAUP committee had found the Koch firing to be “outrageous and completely unwarranted.” The University remained under AAUP censure for three years.[11] The AAUP’s lifting of censure did not come until after the Board of Trustees approved an amendment to the academic freedom provision of the Statutes.

The Koch firing had an enduring effect on the University. Writing in his 1983 memoir, David Henry said the Koch incident had caused “some loss of good will in academic circles.” “I do not think that the scar was too noticeable but one would not have sought it and the University would have been better without it,” Henry admitted.[12] Looking back on the affair ten years later, Koch expressed no regret for writing the letter. “It has been a very enlightening experience and instrumental in changing my life to a happier mold,” Koch told a Daily Illini reporter. “. . . But my position today has changed. Instead of merely condoning sexual intercourse between mature individuals, I now strongly advocate it.”[13]

John Corbally, Henry’s successor, entered office during a time of “falling enrollment, stringent budgets, and declining support from the state and federal governments.”[14] Hoping to stave off financial ruin, the Corbally administration attempted to cut costs by eliminating “unnecessary” academic programs. In the fall of 1973 the Council on Program Evaluation (COPE) began examining academic departments to see which ones made the grade and which ones did not. The Council judged the political science department, for example, to be “under-budgeted and understaffed, over-studented and underspaced, marked by great faculty diversity and a surplus of politics and conflicts.”[15] The College of Veterinary Medicine also received bad reviews; COPE said its “scholarly quality” was “relatively low overall” because of a “crucial lack of qualified staff.”[16] As for the College of Communications, the Council recommended that it be abolished even though it had been highly rated by Columbia University the previous year.[17]

References

[1]David Henry, “Career Highlights and Some Sidelights,” unpublished MS, 1983, 164-65, David Henry Papers (2/12/20), B: 25, F: Memoirs, University of Illinois Archives.

[2]Daily Illini, 17 September 1964.

[3]Ibid., 7 February 1976.

[4]Henry, 176.

[5]Daily Illini, 17 April 1969.

[6]Ibid.

[7]Ibid., 24 May 1966.

[8]Ibid., 2 February 1968.

[9]Ibid., 14 March 1970.

[10]Ibid.

[11]Ibid.

[12]Henry, 186.

[13]Daily Illini, 14 March 1970.

[14]Ibid., 5 April 1974.

[15]Ibid., 14 June 1974.

[16]Ibid., 3 December 1974.

[17]Ibid., 20 November 1975.

Campus Architecture & Planning

During the Depression and war years, the University received little money for buildings, so when baby boomers started flooding the campus,

administrators were forced to purchase 67 formers residences and business properties to accommodate them. It was the equivalent of five buildings the size of Gregory Hall.

In 1960, however, the University secured a $98 million bond from the state which, when combined with increased student fees, enable the construction of 12 new buildings, including Commerce West, the Undergraduate Library, the Assembly Hall, and over 20 dormitories and apartments. Many were modernistic buildings designed by Ambrose Richardson, who later joined the faculty and created a ground-breaking10-year development plan that set forth much of the modern campus as we know it.

The Baby Boomers were coming, and the University was not ready for them. “There was great need for updating facilities,” U of I President David Henry noted. Indeed, the University was suffering from a severe space deficit. During the years of depression and war, the U of I had received little money for buildings, and even in the booming post-war years, the amount of additional building space had failed to keep pace with the growing enrollment. As a result, the University was forced over the years to purchase 67 former residences and business properties and press them into service as classroom buildings, offices, and laboratories. This temporary space equaled the square footage of five buildings the size of Gregory Hall.After securing $98 million from a bond issue approved by the Illinois voters in November 1960, the University launched a massive building program to address its space needs. The building boom ushered in by the bond issue continued in several bursts until the end of the Henry administration in 1971. Notable buildings constructed during this period (not all financed by the bond issue) include Morrill Hall (1963), the Education Building (1964), Commerce West (1964), Turner Hall (1964), the Materials Research Lab (1966), the Newmark Civil Engineering Lab (1967), the Psychology Building (1969), the Undergraduate Library (1969), the Intramural Physical Education Building (1971), and the Foreign Languages Building (1971). The passage of the bond issue proved to be a watershed event in the history of the U of I. According to President Henry, if the bond issue had been voted down, the “Urbana campus could not have accepted the large enrollments that the new buildings made possible,”

Increases in student fees enabled the construction of several other important structures during the decade, including Assembly Hall (1963), the Turner Student Services Building (1962), and the Intramural Physical Education Building (1971). Student fees also made possible the era’s residence hall boom. Between 1953 and 1968, over twenty dormitories and apartments housing thousands of students were built: Noble and Flagg halls in 1953; Taft and Van Doren halls in 1957; Allen Hall in 1957-8; Gregory Drive Residence Halls in 1958; Orchard Place Apartments in 1959; Peabody Drive Residence Halls in 1960-1; Daniels Hall in 1960; Orchard Downs Apartments in 1961; Pennsylvania Avenue Residence Halls in 1962; Illinois Street Residence Halls in 1964; Sherman Hall in 1965-6; Florida Avenue Residence Halls in 1966; and Orchard Downs South in 1968.

Several of these new residence halls were “skyscrapers” that forever changed the look of the formerly low-rise campus. ISR’s twelve-story Wardall, the first high-rise dormitory on the UI campus, soon had some tall companions: Sherman (for graduate students) and FAR’s Trelease and Oglesby halls. Encouraged by the University, private developers also began to build soaring “luxury dormitories” in the mid-1960s: Europa House, Bromley Hall, Hendrick House, and Illini Tower. Rising 17 stories, Illini Tower was the tallest structure near campus until dethroned by the 21-story, aptly named Century 21 apartment/office building in the early 1970s.

Looking back on his years as U of I president, David Henry expressed pride in his accomplishments as a builder. The value of the University’s physical plant had almost quintupled during this period. Henry had an answer to those critics who said that he had been too much of a builder and not enough of an educator. “The emphasis upon building, it must be stressed, was in effect an emphasis upon educational opportunity and upon quality instruction, quality faculty, and quality research,” Henry wrote in his memoirs. “Buildings are for people. To maintain a distinguished University without adequate facilities for its people is not possible.”

Most of these modernistic new buildings had been designed by Ambrose Richardson, an alumnus of the renowned architectural firm Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM). Reduced to, in his own words, “a raving wreck” by the excessive pressures of his job, the 34-year-old Richardson left SOM in 1951 to take a teaching position at the U of I. Richardson’s reputation preceded him, and soon University Architect Ernest Stouffer came calling, offering him the chance to design the new Law Building. Following his work on the Law Building, the young architect’s “stock went up really high,” as Richardson later put it, and soon Stouffer and his boss Charles Havens—director of the Physical Plant Department—began assigning him building project after building project, beginning with the Gregory Drive Residence Halls. Before long, Richardson largely supplanted Stouffer, becoming Havens’ “right-hand consultant on everything” architecturally related.

A student of Mies van der Rohe, Richardson’s stark designs showed the less-is-more influence of Mies. The minimalist Miesian architecture had become the go-to design approach for a generation of post-war architects. “He (Mies) had shown us a way that we thought was the sensible and logical way to design,” Richardson said. “You do it on a modular, sensible, structural system. No nonsense. This is a good way to do it, and so everything became boxes.” Not everyone appreciated the boxy look. Trustee Wayne Johnston, Illinois Central Railroad president and a fan of old-time architecture, once growled at Richardson: “Ambrose, you’ve done more damage to this campus than an atom bomb.”

Like Charles Platt before him, Richardson was a planner as well as a designer. Completed in late-September 1960, Richardson’s ground-breaking Ten Year Development Plan established “the first thinking on expansion since Platt’s 1927 plan,” according to preservation planner Alice Novak. “Thus it was this document that set forth much of the modern era of campus . . . as we know it,” Novak writes. Among other things, the plan called for the retention of the mall concept, a building density of no greater than 25 percent, the general use of low-rise buildings for academic purposes, the grouping of buildings by College, and the banishment of vehicular traffic and student housing to the periphery of the campus. The plan even revived the old idea, once championed by Daniel H. Burnham, of an east-west mall on the South Campus.

The grand plans of the 1960s fell victim to the harsh realities of the 1970s—years of economic stagnation and runaway inflation. Only three academic buildings were constructed on the Urbana campus during the eight-year tenure of President John Corbally, Henry’s successor: the Music Building (1972), the Medical Sciences Building (1975), and the Speech and Hearing Sciences Building (1977). But Corbally’s Food for Century III program would bear fruit early in the administration of Stanley O. Ikenberry, giving the University the Veterinary Medicine Basic Sciences Building (1982) and the Agricultural Engineering Sciences Building (1983).

References

Information for this unit came from Lex Tate and John Franch, An Illini Place: The Campus of the University of Illinois (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, forthcoming).

![]()

Diversity

Diversity was nearly nonexistent at the beginning of the Baby Boom Years. As late as 1967, only half the students were women, and only 1% were African-American. Especially for them, the campus was unwelcoming, with landlords refusing to rent to them, barbers refusing to cut their hair, and local establishments making them unwelcome.

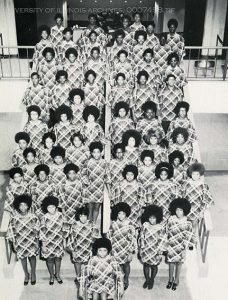

Things changed with Project 500, an effort in 1968 to bolster African-American enrollment. After a rocky start that caused 252 arrests at a student protest concerning housing and financial aid, Project students began forming their own student associations, and convinced the University to create a research program and cultural center for them. This emboldened Latino/a, women’s, and gay-rights groups to push for programs and centers of their own.

David Eisenman’s Oral History of Project 500

Dean of Women Miriam Shelden gave the Daily Illini a snapshot of the student body as it existed late in 1967. There were, Shelden said, 30,407 students on the Urbana-Champaign campus—20,173 men and 10,234 women. The students came from all 102 counties in Illinois, from every state except Alaska, and from 85 foreign countries.[1] Shelden did not provide information on the racial and ethnic make-up of the student body but she could have: in 1965 the University began systematically collecting such data for the first time.[2] According to the numbers, in 1967-68 there were only 330 African American students in Urbana-Champaign—one percent of the student body. The University responded by launching the Special Educational Opportunities Program—Project 500–in an effort to bolster African American enrollment.[3] The students brought to the campus by Project 500 demanded to be seen and heard, and their fight to create a more representative university inspired other groups such as women and Latina/o/xs.[4] Diversity was on the march.

The 1950s began with African Americans and their white allies combating local discrimination in fraternities, rooming houses and barber shops. Campus-area barbers refused to cut the hair of African Americans; even J. C. Caroline, the All-American halfback and future College Football Hall of Famer, was denied service.[5] In the fall of 1954 members of the Student-Community Human Relations Council picketed the Campus Barbershop on the corner of Sixth and Daniels streets. Lee Ingwersen, owner of the Campus Barbershop, attempted to defend himself against his critics. “Since barbering is on such a close personal basis, I do not believe the trade should be mixed,” Ingwersen said.[6] Despite the efforts of civil rights groups, barber shop discrimination continued. As late as 1959, a barber refused service to a visitor from Jamaica.[7]

Housing discrimination remained a problem for African Americans and international students. In 1953 an anti-discrimination group sent “two foreign students of dark complexion, followed in (a) half-hour by two white students” to all of the University-approved rooming houses within a half-mile of Illini Hall and found that 35 percent of the landlords were unwilling “to rent their rooms to foreign students, at least those who are not white.”[8] In 1955 a local NAACP chapter was organized and immediately began pressuring the University to remove all rooming houses that discriminated from its list of approved housing.[9] At first University officials rejected the NAACP’s appeals, citing a shortage of housing, but eventually, in 1960, the school’s Code of Fair Educational Practice was revised so as to require the owners of new rooming houses to make their “facilities available to all students without discrimination with respect to race or religion.”[10] The rule was ultimately extended to include all rooming houses, new and old.

The campus racial climate was improving, but it was far from perfect. An anonymous football player described the social situation of the African American student in 1964: “The day after Homecoming, whether we win, lose, or draw, the Negro athlete and the Negro student is completely without facilities, completely without anything to do unless we go to town or unless we go to some activities that are off campus. One of the main things that I tried to point out to students who come here is that there is no social life for him whatsoever, and if you are not involved in the little personal clique that exists on campus, then essentially you are in trouble.”[11] The complaint was a familiar one: back in the early 1900s, Maudelle Tanner Brown and her friends spent their Sundays in an African American church listening to the music and watching the services because there “wasn’t anything else to do.”[12]

Project 500 changed things for the African American student, helping create a vibrant and cohesive African American community on campus. The program, however, got off to a rocky start. On the night of September 9, 1968, students gathered at the Illini Union to air their grievances over certain aspects of Project 500, with dormitory assignments and financial aid arrangements being particular sore spots. The following morning, police arrested some 252 of the students at the Union after “acts of vandalism were committed by a very small number of disorderly persons”–persons said to be “outsiders.”[13] The mass arrests unified the Project 500 students and pushed many of them into activism. According to Jeffrey Roberts, a student of the era, the arrests “actually brought people closer together.” “It really brought things into focus for me personally,” Roberts continued. “After that experience, we knew we really had to watch each other’s back.”[14]

In the wake of the Project 500 arrests, a Black Power movement flourished on campus. Led by the Black Student Association, activists prodded the University administration to establish the Afro-American Studies and Research Program and the Afro-American Cultural Program.[15] The Association published various newspapers throughout the years, including Drums and Black Rap, and the yearbook Irepodun (Swahili for “unity is a must”) and employed them as “forums for Black arts and expression,” in the words of historian Joy Ann Williamson.[16] The Black Power movement fractured during the 1970s; by 1975 there were over thirty different African American groups on campus.[17]

Other groups followed the lead of African Americans and demanded to be heard. Latina/o students asked for a full-time advisor, called for the recruitment of more Latina/os, and in 1974 established a campus home for Latina/o students–La Casa Cultural Latina.[18] Energized by the civil rights and anti-war movements, female U of I students formed a host of women’s organizations on campus and pushed for gender equity. University administrators responded: in 1970 the U of I offered its first Women’s Studies course, and the Office of Women’s Resources and Services was established; in 1971 Chancellor Jack Peltason appointed the Committee on the Status of Women to investigate issues affecting women as students and personnel, and later that year the decision was made to allow women in the Marching Illini; in 1974 the Women’s Wheels program was inaugurated to offer women “a safe alternative to walking alone at night”; and in 1978 the Office of Women’s Studies was founded.[19]

Gay and lesbian students also fought for their rights. To be gay on college campuses prior to the late-1960s and early-1970s was to live a closeted existence. Homosexuals faced ridicule from other students, a clandestine social atmosphere, and a psychological establishment that believed that homosexuality was something that could be, and should be, “cured.” Mirroring a national trend, gay-rights activists worked in the 1970s to pass anti-discrimination ordinances in Champaign and Urbana and to create a more tolerant educational and social environment on the campus and in the community. In about 1970 the Gay Liberation Front formed on campus; the GLF was an off-shoot of the national organization that had emerged in the wake of the 1969 Stonewall uprising in New York City. The stated purpose of the group was “to advance the political and social rights of homosexuals through education of the heterosexual community.”[20] In 1972 Gay Liberation Front members picketed the Wigwam Bar on Sixth Street, accusing its employees of harassing gay patrons. “So many ‘accidents’ have occurred at the Wigwam that it’s disgusting,” a GLF member asserted. “We have been shoved around and had drinks spilled on us.”[21] Not long after the picketing campaign, the Wigwam closed its doors, re-opening the following autumn as the Round Robin.[22] The local Gay Liberation Front disbanded early in 1974. The Gay Students’ Alliance, a new, more moderate group, subsequently formed on campus and was renamed the Gay Illini in the fall of 1975.[23]

References

[1]Daily Illini, 15 December 1967.

[2]William K. Williams, “University Activity in the Area of Human Relations and Equal Opportunity, 1965-66,” David Henry General Correspondence (2/12/1), B: 188, F: Human Relations and Equal Opportunity, University of Illinois Archives.

[3]Williams to David Henry, 2 August 1968, ibid.

[4]Joy Ann Williamson, Black Power on Campus: The University of Illinois, 1965-75 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003), 140.

[5]Ibid., 21.

[6]Daily Illini, 8 October 1954.

[7]R. W. Jugenheimer to L. B. Howard, 28 October 1959, David Henry General Correspondence (2/12/1), B: 51, F: Racial Minorities.

[8]Paramesh Ray to Lloyd Morey, 23 October 1953, Dean of Students Correspondence File (41/1/1), B: 18, F: Morey.

[9]Joseph Ewers to Henning Larsen and A. J. Janata, 22 July 1955, ibid., B: 21, F: Ewers.

[10]Williamson, 21.

[11]Transcript of Audiotape, Duplicated 28 May 1964, David Henry General Correspondence (2/12/1), B: 131, F: Discrimination.

[12]Quoted in Chicago Defender, 5 March 1970.

[13]“Findings of Fact,” In the Matter of David N. Addison, Transcript, 3-22, 16 December 1968, David Henry General Correspondence (2/12/1), B: 215, F: Student Disruption.

[14]Williamson, 93.

[15]Ibid., 134.

[16]Ibid., 98.

[17]Ibid., 135-36.

[18]Daily Illini, 19 December 1972; 28 March 1973; 1 January 1975.

[19]Daily Illini, 16 September 1970; 26 February 1971; 16 September 1971; 10 December 1974.

[20]“The University of Illinois in the Cold War Era 1945-1975: Gay Rights on Campus,” LibGuide, University Library, online at http://guides.library.illinois.edu/c.php?g=348250&p=2350893

[21]Daily Illini, 15 April 1972.

[22]Ibid., 17 October 1972.

[23]Ibid., 29 October 1975.

![]()

Student Activities

Student apathy was rife in the 1950s, but that changed dramatically by the early 1960s. First with civil rights, then with anti-Vietnam War activism, students began holding constant, major demonstrations, leading President Henry to state that the University was “at the vortex of a social storm.” A week-long strike in May 1970 against expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia, in fact, led to 105 arrests.

Most students, however, were more interested in life in general. By the late 1960s, the sexual revolution was in full evidence on campus, and as always, most disciplinary actions involved liquor. By the end of the 1970s, students became more interested in potential careers, leaving politics by the wayside.

Even in the mid-1950s—the height of the Eisenhower era–some students bemoaned the political apathy then prevalent on campus–and in the country at large. “Imaginations are being stepped on all over the place nowadays,” Daily Illini columnist Bob Perlongo wrote that year, “romance even is becoming ugly and instead of virility and vigor there is a deadly white national pasty-faced expression of indifference.”[1] A little over a decade after Perlongo’s utterance, thousands of students would take to the streets to protest censorship, the Vietnam War, recruitment by military contractors, and racial and sexual discrimination in their many forms. Suddenly, the nation’s universities were, in the words of President David Henry, “at the vortex of a social storm.”[2] Panty-raids had given way to political protest.

According to the Daily Illini reporter Paul Ingrassia, 1960s activism at the University went through three stages: between 1960 and 1965, activists focused on civil rights; between 1965 and 1967, they addressed mostly local matters; and, after 1967, they took on national issues, primarily the Vietnam War.[3] It was an exciting time for many. “There was always something going on,” a former student recalled of the period. “It was wonderful. As soon as one demonstration was over, we went on to play the next.”[4] Major demonstrations of the period included the 1967 sit-in protests against Dow Chemical recruiting, the October 1969 moratorium against the Vietnam War, the March 1970 rally against General Electric, and the May 1970 student strike.[5]

Not all 1960s-era students, however, were activists. “The largest group of students was not in the anti-war movement,” William Bates, an undergraduate in the late-1960s, maintained. “It is a current misconception to believe that most students were in the anti-war movement. The majority was too busy going to college.” According to Bates, many non-activists attended the demonstrations because they were entertaining, had free music, and “there was a lot of free drugs and booze floating around.”[6]

The strike of May 1970, however, had widespread support, from activist and non-activist students. Called to protest the expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia and the killing of four Kent State students by National Guardsmen, the strike lasted about one week and seriously disrupted the campus. The major event of the strike occurred on May 9th when a phalanx of State Police, supported by University police, Urbana police, and National Guardsmen, executed a military maneuver and encircled a group of students—protester and non-protester alike—on the Quad. One hundred and five students were arrested and transported by bus to Memorial Stadium where they were detained for many hours before being booked at the Sheriff’s Office.[7] In a telephone survey conducted by the Office of the Dean of Students later in the month, 64 percent of respondents endorsed the May strike. Defending the strike in letters to parents, Acting Dean of Students Hugh Satterlee said that conservative and non-radical groups had participated in it. “Important questions were being asked and there seemed to be a lot of concern for the principles involved,” Satterlee wrote.[8]

“Make Love Not War” was a popular slogan of the time. Many students practiced what they preached in an era of easily available birth control and changing sexual norms. Writing to President Henry in 1966, a parent complained of her visit to the Lincoln Avenue Residence Halls where “every nook and corner” was a “Passion-pit.” “As we walked up the circular walk to L. A. R. at 10 a. m. there were three USED contraceptives right ON the sidewalk,” the irate parent declared. “How many more were in the bushes?”[9] By the late-1960s, the sexual revolution was in full evidence. “Lots of warm bodies in the cemetery on warm summer nights,” William Bates remembered. “Free love was every where. The ‘flower children’ were enjoying the summers and so was I.”[10]

Many students enjoyed drinking as well. In 1964 Security Officer W. Thomas Morgan estimated that sixty percent of all student disciplinary cases involved liquor. Some students under the legal age of 21 were so eager to “get into the bars” that they attempted to alter their driver’s licenses or their University IDs.[11] This practice helped inspire one of the most infamous incidents in University history—the Kam’s Raid of February 25, 1966. That Friday night “investigators” from the Illinois Secretary of State’s Office descended upon Kam’s and arrested between 50 and 75 students suspected of being under-age. J. Bradley Hull was one of those arrested. “As a 19 year old sophomore, I was in the dingy basement drinking 3.2% draft beer with my fraternity brothers on a Friday night,” Hull recalled. “Noticing men standing around in trench coats, we asked a senior, Bill Cocagne, who they were and he replied they must be ‘recruiters visting campus.’ Within two minutes, one of these recruiters turned off the music and announced ‘stay where you are, this is a raid.’ With hundreds of students jammed into two floors of Kam’s, it took at least an hour for these undercover agents to check each student’s ID . . . and separate the underage ones from those over 21. The adults resumed their alcohol consumption and a contemporary tune titled I Fought the Law and the Law Won played repeatedly on the jukebox.”[12]

In the 1970s, “hitting the bars” was as popular as ever. According to the Daily Illini, on the single night of March 23, 1972, some 2,000 students, “their hands barely able to hold a glass of beer after a strenuous week of notetaking,” crammed into nine campus bars offering something for everyone. The bars included the Wigwam, “a down-home bar” catering to “the longer haired people;” the Red Lion, a pub attracting “all types” and famous as a venue for rock groups like REO Speedwagon; Murphy’s, the favored lair of the graduate student then and now; Dooley’s, “the best place to meet girls;” and Whitt’s End, “the best place to meet boys.”[13] According to local legend Mark Rubel, “each bar had its own scene. There were the regulars and the weirdos and the beautiful girls and strange people and the shady people and the out-and-out criminals. It was like a cartoon.”[14] Not that they needed it, but campus bars got a boost in 1973 when Illinois law was revised to allow 19-year-olds to drink beer and wine.[15]

Drug use became a major issue for University administrators in the late-1960s. The problem, though, was not exactly a new one on campus: way back in 1921, for example, Dean of Men Thomas Arkle Clark claimed that a student had obtained opium and hypodermic needles at an ice cream parlor, and more recently, in 1964, the Subcommittee on Undergraduate Discipline heard the cases of three individuals who had sold amphetamines to students.[16] But the scale of the problem grew exponentially during the late-1960s. Chancellor Jack Peltason became concerned late in 1968 when rumors began to circulate of drug use in certain University residence halls.[17] The following year Associate Dean of Students Stanley Levy reported hearing that the 12th floor of Oglesby was especially “notorious” for drug use.[18] University administrators scrambled to develop a policy regarding drugs. In the fall of 1969, Acting Dean of Students Hugh Satterlee explained the University’s emerging philosophy on the issue to a Chicago Tribune reporter. “We have been trying to set up an atmosphere of treating drug use as a counseling and medical problem, not a criminal act,” Satterlee said.[19]

By the mid-1970s, student life had settled down to a familiar rhythm–perhaps quieted in a measure by the recently enacted housing and academic reforms. In the spring of 1974 some students were still out in the streets, but they weren’t protesting: they were shedding their clothes—streaking–in the latest college fad to hit the nation’s campuses.[20] Students still wore longish hair and blue jeans, but the political climate had become more conservative. This change was reflected in a poll of 1,068 students conducted before the 1976 presidential election: the Republican Gerald Ford received 47 percent of the vote, trouncing Democrat Jimmy Carter by 16 points. Many undergraduates came to view college as principally a pathway to a lucrative career. For these students, money trumped politics. “I want to have a lot of money,” an actuarial science major told a DI reporter in 1977. “I’d like to find something interesting and then I want it to pay.”[21]

[1]Roger Ebert, An Illini Century: One Hundred Years of Campus Life (Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1967), 178.

[2]David Henry, “Career Highlights and Some Sidelights,” unpublished MS, 1983, 290, David Henry Papers (2/12/20), B: 25, F: Memoirs, University of Illinois Archives.

[3]Daily Illini, “New Student Edition,” August 1970.

[4]Ibid., 3 May 1975.

[5]Ibid., August 1970.

[6]William Bates to Ellen Swain, undated, William Bates Papers (41/20/203), University of Illinois Archives.

[7]John Metzger to Jack Peltason, 15 May 1970, David Henry General Correspondence (2/12/1), B: 221, F: Campus Disruptions, University of Illinois Archives.

[8]Patrick Kennedy, “Reactions against the Vietnam War and Military-Related Targets on Campus: The University of Illinois as a Case Study,” Illinois Historical Journal 84 (Summer 1991), 115.

[9]“Parents who saw” to David Henry, 21 March 1966, Dean of Students Correspondence File (41/1/1), B: 47, F: Henry.

[10]Bates to Swain.

[11]W. Thomas Morgan to Carl Knox, 28 November 1962, Dean of Students Correspondence File (41/1/1), B: 38, F: Morgan.

[12]J. Bradley Hull to Ellen Swain, 12 February 2003, J. Bradley Hull Papers (41/20/170), University of Illinois Archives.

[13]Daily Illini, 11 August 1972.

[14]Quoted in Doug Peterson, “The School of Rock,” Illinois Alumni 25 (Fall 2012), 28.

[15]Daily Illini, 2 October 1973.

[16]Thomas Arkle Clark to David Kinley, 10 February 1921, Dean of Men General Correspondence (41/2/1), B: 24, F: Kinley; W. Thomas Morgan to Fred Turner, 20 January 1964, Dean of Students Correspondence File (41/1/1), B: 41, F: Morgan.

[17]Stanton Millet to Stanley Levy, 22 October 1968, Dean of Students Subject File (41/1/6), B: 9, F: Drug Problems.

[18]Stanley Levy to John Scouffas, 23 May 1969, ibid.

[19]Hugh Satterlee, “Memorandum for the Record,” 21 October 1969, ibid., B: 9, F: Drugs and Narcotics.

[20]Daily Illini, 9 March 1974.

[21]Ibid., 16 February 1977.

The Boomer years saw a revolution in student regulation. Into the early 1960s, women were still forbidden to visit men’s dormitories without a chaperone, students’ couldn’t live in apartments without permission, homosexuality could get a student expelled. “Racy” publications like Shaft, edited by students Gene Shalit and Hugh Hefner, and “subversive” organizations or speakers were all bones of contention in the eyes of longtime Dean of Students Fred Turner.

With Fred Turner’s retirement in 1966, things changed dramatically. His replacement, Stanton Millet, asserted that the days of “in loco parentis” were over. Expulsion for “moral grounds” stopped, and most living restrictions were lifted. Student course evaluations were introduced, and for the first time students were allowed to develop individual degree programs.

David Bechtel and Hugh Satterlee Oral History

During the 1950s and much of the 1960s, the long-standing policy of in loco parentis remained in force against students at most of the nation’s universities, including the U of I. Writing in 1942, U of I Counsel Sveinbjorn Johnson had defined this policy as meaning “in one aspect that the University may deal with the students, discipline them, lay down reasonable prohibitions upon certain types of conduct in general to the same extent that a parent might, were the young man or the young woman domiciled with the parent.”[1] In other words, the University assumed the role of parent to the students. Dean of Students Fred Turner and his right-hand man, Security Officer W. Thomas Morgan (who had succeeded Joseph Ewers in 1956), served as the campus’ primary enforcers of in loco parentis.

Turner, Morgan, and other like-minded University officials were determined to create a “moral climate” on the campus. All unmarried undergraduates were required to live in University-approved housing and could not reside in an apartment without the approval of either the deans of men or women. Women could not visit a men’s residence hall unless a chaperone was present; men, on the other hand, could visit women’s residence halls but only for limited times. (Closing hours for women’s residence halls were 10:30 p.m. Sunday through Thursday and 1:00 a.m. on Friday and Saturday.)[2] Any undergraduates using or possessing “intoxicants” in University residence halls were “subject to dismissal.”[3] Certain student publications were frowned upon: in 1954 the Senate Committee on Student Affairs cracked down on Shaft, a racy publication once edited, at different times, by Gene Shalit and Hugh Hefner.[4] So-called “subversive” organizations and speakers were barred from campus.[5] No less of a figure than Thurgood Marshall, the future Supreme Court justice, received a background check before he was allowed to speak on campus; according to Fred Turner, Marshall’s speaking engagement could be approved “without any qualms of conscience,” even though Security Officer Joseph Ewers’ report on the NAACP counsel contained “some items which might be questioned.”[6]

The Security Office even attempted to police the sexual behavior of students. However, beginning in the late-1950s, the Subcommittee on Undergraduate Student Discipline became increasingly reluctant to handle cases involving “sex practices and conduct of a man student and a woman student,” in the words of Security Officer W. Thomas Morgan. A 1961 meeting called to iron out policy in such cases turned into “a fiasco and a purge,” Morgan reported, “and as little was accomplished as I have ever experienced from a meeting.”[7] On the other hand, Security Office procedures dealing with homosexuality were well-established. A subject caught in an “overt act” was interviewed and then referred to the Mental Health Unit of the University Health Service. After receiving the Mental Health Unit’s prognosis, the Security Office could either refer the person back to the Mental Health Unit or to the Subcommittee on Undergraduate Student Discipline for possible dismissal from the University. This decision hinged on the subject’s willingness to “undergo therapy.”[8]

The old administrative order began to crumble in the early-1960s. In June 1962 the national Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) issued its famous Port Huron Statement, which, among other things, called for students and faculty to “wrest control of the educational process from the administrative bureaucracy.” Over a year later, Dean of Students Fred Turner informed President Henry of these words (underlining them for emphasis) and warning him that SDS “might be one source of a continuing agitation against educational administration.”[9] The “agitation” reached Turner’s very doorstep in October 1965 when the Student Committee on Political Expression (SCOPE)–formed in the wake of the Berkeley free speech movement to “define the students’ interests”–protested “the paternalistic attitude of the University” in front of the Student Services Building (later the Fred Turner Student Services Building). “Dean Turner has been picketed because he represents an archaic and discredited style in dealing with students,” Joe Allen, a SCOPE member, declared.[10]

Students might have picketed Turner for other reasons had they known he was an “associate” of the Central Intelligence Agency. Since the mid-1950s, Turner had served the Agency as a recruiter of sorts.[11] When news broke in 1967 that the CIA had been funding the National Student Association (the country’s largest college student organization), Emmett D. Echols, the CIA’s director of personnel, wrote Turner a letter of advice. “My only suggestion and request is that you not involve yourselves in the general public controversy,” Echols stated. “We ask only that, if you should be drawn unavoidably into the arena administratively or otherwise, you speak well of the Agency and counsel a ‘wait for all the returns’ posture.”[12]

Turner’s long tenure as Dean of Students ended in September 1966, just as the pace of student protest began to quicken. Stanton Millet, Turner’s successor, bowed to the inevitable. “It has become increasingly clear that the day of an effective role for the university in loco parentis is over,” Millet asserted at the end of his first year in office. “Our students are not boys and girls, but men and women.”[13] Under Millet, the post of Dean of Men became the Dean of Student Programs and Services and the Dean of Women was given an additional title–Dean of Student Personnel. Millet believed that dividing “administrative responsibilities for student affairs according to the sex of the students is no longer effective or particularly meaningful.”[14]

Responding to student pressure, University administrators such as Millet granted undergraduates an unprecedented degree of latitude in running their own lives. These liberalizing reforms began in the late-1960s and continued into the 1980s. In the matter of housing, juniors, seniors, and eventually sophomores were permitted to live off campus. Some residence halls became co-educational, visitation hours were eliminated, and overnight dates in dorm rooms were sanctioned. Beer and wine were even allowed in dorm rooms and at floor parties. In the academic realm, students could no longer be expelled on so-called moral grounds, but only for “anti-social conduct or failure in academic work.” Students were given the ability to rate teacher performance through Course Evaluation Questionnaires, permitted to develop their own individual degree programs, and extended the option of taking classes on a pass-fail basis.[15] Even more so than the landmark periods of the Burrill and Chase administrations, the era of the late-1960s and early-1970s revolutionized student life.

References

[1]Sveinbjorn Johnson to Arthur Willard, 25 May 1942, Dean of Men General Correspondence (41/2/1), B: 76, F: Willard, University of Illinois Archives.

[2]Fred Turner to David Henry, 8 January 1964, Dean of Students Correspondence File (41/1/1), B: 42, F: Residence Halls Closing.

[3]Daily Illini, 27 May 1961.

[4]Ibid., 9 April 1954; Fred Turner to Lloyd Morey, 30 March 1954, Dean of Students Correspondence File (41/1/1), B: 18, F: Morey.

[5]Daily Illini, 27 October 1955.

[6] Fred Turner to A. J. Janata, 30 January 1956, Dean of Students Correspondence File (41/1/1), B: 21, F: Janata.

[7]W. Thomas Morgan to Carl Knox and Miriam Shelden, 5 October 1962, ibid., B: 38, F: Morgan.

[8]Morgan to John Templin, 5 March 1965, ibid., B: 44, F: Morgan.

[9]Fred Turner to David Henry, 24 September 1963, ibid., B: 41, F: Henry.

[10]Daily Illini, 14 October 1965.

[11]Fred Turner to Lloyd Morey, 25 April 1955, Dean of Students Correspondence File (41/1/1), B: 19, F: Morey.

[12]Emmett D. Echols to Fred Turner, 24 February 1967, Fred Turner Papers (41/1/20), B: 7, F: CIA.

[13]Stanton Millet, “Student Affairs: The Year Ahead,” Faculty Letter 141 (27 June 1967), 1.

[14]Stanton Millet to Jack Peltason, 15 August 1967, David Henry General Correspondence (2/12/1), B: 185, F: Dean of Students.

[15]Daily Illini, 16 February 1977.

![]()

Traditions & Sports

During the 1953-1979 period, University traditions waxed and waned. In the 1950s, such traditions—both official and unofficial—thrived. Homecoming, Dad’s Day, and Mom’s Day still attracted large crowds to the campus. Beginning humbly in 1944, the Spring Carnival became a major Midwestern event the following decade. On the unofficial side of things, there were the so-called “water riots”: the first one occurred in 1957 and featured thousands of students frolicking in the gushing streams of opened fire hydrants. But, as the 1960s progressed into the 1970s, students increasingly began to question the relevance of campus traditions. Even so, one of the most enduring University traditions of all time was created during this period—Quad Day.

The first official Quad Day occurred in the fall of 1971. According to then-Dean of Student Programs and Services Dan Perrino, the event had been created in order to promote a sense of community on a campus wracked by protest and dissension. “They [students] were just in general angry with the adult population—they didn’t trust them,” Perrino later explained. “So, we wanted to do something whereby students and faculty would talk to each other. That was the original idea, at least from my point-of-view.” Over 7,000 people attended the first Quad Day, which, besides the usual student organization booths, featured such highlights as a volleyball game, a hot dog stand, and a faculty and student talent show. Willard Broom, a future associate dean of students, was present at the creation of Quad Day. Speaking in 2010, Broom deemed the inaugural edition of what would become a beloved tradition to be “a surprising success.” “Everybody loved it,” Broom declared. “Everybody had a good time. It was relaxed. It was outside. Everybody’s excited.”[1]

Quad Day succeeded in a climate not very congenial to tradition. Homecoming offers a case study in the declining popularity of tradition during this era. Homecomings in the 1950s boasted large attendances and often memorable football games. As late as 1965, Homecoming remained an important student ritual: the Daily Illini called that year’s celebration “one of the all time best.” Just three years later, however, Homecoming seemed, for many students, to be old-fashioned and out of date in an era of political protest: in a stab at relevance, that year’s Homecoming Stunt Show included skits dealing with such politically charged topics as the Vietnam War and student power. Perhaps not surprisingly, the Stunt Show—a “barometer of student sentiment” for nearly 50 years—was never held again. In 1970 organizers again strove for relevance, instituting Homecoming Saturday symposiums, putting up anti-war Homecoming decorations, and selling a stop-sign-shaped Homecoming badge boasting a slogan with a double meaning, WHEN THE BOYS COME HOME. By the late-1970s, student sentiment had shifted, and Homecoming seemed poised for a comeback.[2]

Chief Illiniwek also came under fire for the first time. Early in the 1970s, Native American groups began protesting sports teams’ use of Native American names and imagery. Responding to the criticism, Stanford University re-vamped its “Indians” symbol, the Marquette Warriors dropped their “Willie Wampum” mascot, and the University of Nebraska at Omaha changed its nickname from “Indians” to “Mavericks.”[3] According to the 1975 Illio, U of I officials removed the Chief Illiniwek symbol from University stationery in order “to appease AIM (American Indian Movement).” But the controversy was only beginning. “Chief Illiniwek is a mockery not only of Indian customs but also of white people’s culture,” Bonnie Fultz, an executive board member of Citizens for the American Indian Movement, told an Illio writer. A. Webber Borchers, the second Chief, disagreed. “It’s the most outstanding tradition of any university in the land, with no intention of disrespect to the Indians,” Borchers said of the Chief.[4] In the late-1970s, the controversy played out in the letters to the editor columns of the Daily Illini: full-scale protests of the Chief would not commence until a decade later.

Old traditions like Homecoming and the Chief survived the period, but one fairly new tradition—the Spring Carnival—went the way of the Interscholastic Circus—an event which it closely resembled. Beginning life in 1944 as a University Mardi Gras, this humble affair had been launched by the Mortar Board honor society as a means of raising money for the Red Cross. The following year the Mardi Gras became the Illini Pow Wow under the sponsorship of the Illini Union Board. Between 1947 and 1955, the weekend event was known as the Spring Carnival and reached its peak of popularity. “From every university and college in the Midwest area and from every corner of the state,” the Daily Illini claimed, “students, adults, and children would pack up for the celebrated UI weekend.” Visitors to the Armory were treated to row after row of student-created “participation

booths, movies, and skits”; trophies were given to the exhibits judged to be the best. After a hiatus in 1956, the Spring Carnival continued with new names—first Campus Fair in 1957 and then Sheequon (supposedly a Menominee word meaning “spirit of spring”)–until its demise in 1960.[5] The Student Senate killed Sheequon that year, deeming it “a tremendous waste of time and money.”[6]

University officials put an end to the “water riots” one year after the death of Sheequon. An unofficial tradition to say the least, the “water riots” represented a return to the “rowdyism” of past years. Occurring on Memorial Day 1957, the first one began innocently enough with the women occupants of a rooming house and the members of two fraternity houses engaging in “a friendly water fight.” Other people joined “the splash party,” and the group started roaming the campus area, attracting followers that swelled its size to between 300 and 500 persons. Hearing rumors of student arrests, the members of the crowd headed to Champaign but were rebuffed at the Springfield Avenue viaduct by State Police and Sheriff’s Office deputies using tear gas. Twenty-eight students and three townspeople were arrested during this incident.[7] During the following year’s water riot, a University Police officer was hit in the face by “a full bucket of water.”[8] The inevitable serious injury happened in 1961 when a local radio newsman was struck in the head and partially blinded in one eye. The University cracked down hard on the water riot participants, with the Subcommittee on Student Discipline expelling 37 students for their part in the affair.[9] The short-lived water riot “tradition” passed into history.

Another unfortunate “tradition”–that of losing Illinois football teams—took hold during this period. Between 1953 and 1979, Illinois had five football coaches—Ray Eliot (1942-59); Pete Elliott (1960-66); Jim Valek (1967-70); Bob Blackman (1971-76); and Gary Moeller (1977-79)–and only two Big Ten championships, one in 1953 and the other in 1963 (followed by a 17-7 Rose Bowl victory against Washington). Of these coaches, Blackman had the best winning percentage in Big Ten games, with 51.6%; Valek had the worst, a measly 17.8%.[10] Fan reaction to Illinois football’s losing ways was predictable. In a 1978 letter to U of I Chancellor William Gerberding, an anguished alumnus criticized what he believed was “a lackadaisical attitude towards winning by the administration.” “After the Purdue game, many students from the Block ‘I’ took sarcastic glee in shouting in unison, ‘We’re Number Ten!’” the alumnus reported. “The chant was so close to being true, it hurt.”[11]

Illinois basketball was not in a much better place. Illinois had four basketball coaches during this period–Harry Combes (1947-67); Harv Schmidt (1967-74); Gene Bartow (1974-75); and Lou Henson (1975-96)–and only one appearance in the NCAA Tournament, in 1963. But better days were ahead for the Assembly Hall faithful: Lou Henson, who assumed the coaching reins in 1975, would lead the Illini to four NCAA Tournament appearances during his long tenure.[12]

The so-called “slush fund scandal” made a bad situation even worse for Illinois athletics. In the early-to-mid-1960s, Athletic Director Douglas Mills had set up three “slush funds” outside of the University, the proceeds of which were used to “help out” athletes on the football and basketball teams. The Big Ten Conference severely penalized the University’s athletic program for these “under the table” payments to student athletes. Three coaches, including Pete Elliott and Harry Combes, were forced to resign in 1967, and five athletes were declared permanently ineligible.[13] “The penalties were much more severe than we expected,” President Henry wrote in his memoir, “and I felt that they were unfair and unjust.”[14]

Women’s athletics received a big boost with the 1972 passage of Title IX prohibiting sex discrimination in colleges and universities. Despite the provisions of Title IX, women athletes struggled for respect during the 1970s: they had to pay most of their expenses and were denied access to equipment and facilities. In 1974 the entire budget for the U of I women’s sports program was only $15,000. The following year the budget was boosted to $82,000, but even that larger figure paled in comparison to the $2 million-plus annual budget of the men’s sports program.[15] In 1977 two Illini athletes filed suit against the UI Athletic Association to force its compliance with gender equity. The NCAA initially opposed Title IX and would not begin administering women’s athletics programs until 1980.[16] Nonetheless, Illini women athletes persevered The women’s basketball team first took the court in 1974, playing in relative obscurity, and by 1982 had obtained its first berth in the NCAA Tournament; the next season–1982-83–would be its first in the Big Ten.[17]

References

[1]Anna Trammel1, “The First Quad Day,” University of Illinois Archives Blog, online at http://archives.library.illinois.edu/slc/the-first-quad-day/

[2]John Franch, “Illinois Homecoming: A Century of Spirit,” Illinois Alumni 23 (Fall 2010), 27-29.

[3]Urbana Daily Courier, 21 January 1972.

[4]Illio 75, (Urbana: Illini Publishing Company, 1975), 154-55.

[5]Daily Illini, 31 March 1960.

[6]Ibid., 1 August 1960.

[7]Fred Turner to David Henry, 11 June 1957, Dean of Students Correspondence File (41/1/1), B: 23, F: Henry.

[8]Sergeant Harry to W. Thomas Morgan, 22 April 1958, ibid., B: 26, F: Water Riot.

[9]Ebert, 202.

[10]“List of Illinois Fighting Illini head football coaches,” Wikipedia, online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Illinois_Fighting_Illini_head_football_coaches

[11]Ross Gilfillan to William Gerberding, 27 October 1978, John Corbally General Correspondence (2/13/1), B: 127, F: Comments and Criticisms.

[12]“Illinois Fighting Illini men’s basketball,” Wikipedia, online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illinois_Fighting_Illini_men%27s_basketball

[13]Daily Illini, 14 January 1967.

[14]David Henry, “Career Highlights and Some Sidelights,” unpublished MS, 1983, 213, David Henry Papers (2/12/20), B: 25, F: Memoirs, University of Illinois Archives.

[15]Daily Illini, 6 November 1973; 30 March 1974.

[16]“The University of Illinois in the Cold War Era 1945-1975: Women’s Athletics at the University of Illinois,” LibGuides, University of Illinois Library.

[17]“Illinois Fighting Illini women’s basketball,” Wikipedia, online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illinois_Fighting_Illini_women%27s_basketball