One fateful day in 1920 a grisly discovery sparked a violent riot that would shake the small mining community of West Frankfort, Illinois. On August 5th several hunters were trapesing through the woods searching for squirrels. Instead, they of finding the charming rodents they had been hoping for, they stumbled across a crime scene. There, amongst the brush, were the bodies of two teenage boys. The bodies would later be identified as Tony Hemphill and Amiel Calcaterra. Hemphill and Calcaterra’s throats had been cut and their bodies shoved in a shallow grave.[1]

Three men were quickly taken into police custody for their suspected role in the crime. Locals, however we not content to let the justice system run its course. Upon hearing news of the arrests, a mob quickly gathered outside of the jail, demanding to speak to the prisoners. Seemingly anxious to appease the crowd, the police offered a limited number of mob members into the jail to ask the prisoners questions. While representatives from the mob were allowed to ask questions, the police intended to use this moment as a distraction. As a representative was relaying the inmates’ answers officers smuggled them out and moved them to a safer location.[2]

News of this trick quickly spread through the crowd. Now lacking a specific target for their anger, the mob turned their attention to West Frankfort’s Italian immigrant community. They ravaged through the town, setting fire to homes and beating any immigrants that crossed their path. The town’s Italian population was forced to flee, many running on foot, as they sought protection in nearby areas. Businesses too became the target of would be arsonists. Before long the local telegraph lines had been cut, hampering communication with those outside of the city. Knowing that they were outmatched, the local law enforcement sent requests for state troops to help calm the chaos. [3] Nevertheless, violence continued throughout the night and into the next morning.[4]

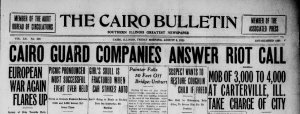

In the breathless news coverage that followed, rumors and misinformation began to swirl. From the start, newspapers were unable to agree on the ages, and name spellings, of the murdered boys. According to the Cairo Bulletin, Tony was 20 while Amiel was 14.[5] However, the Macomb Daily By-stander puts Tony’s age at 17 and Amiel (here spelt Emil) at 14.[6] Initial reports on the riots put the death toll between seven and five, with some articles including the story of a photographer who was killed in the midst of the mob while taking pictures. Around 50 homes were also said to have been set ablaze in the chaos.[7] Later reports showed more mitigated results, stating that no deaths occurred during the rioting and that six houses were burnt and three stores destroyed.[8]

An especially interesting rumor stated that the city’s Italian community had, in part, been targeted because of previous Blank Hand Society activity in West Frankfort. The organization was said to have been distributing pamphlets in the area though the exact content of these documents is not clear.[9] Previous mentions of Black Hand Society in the Illinois Digital Newspaper Collections show that the Black Hand often engaged in extortion and death threats.[10]

When the dust settled the story began to clear somewhat. One death did occur as a result of the riot, that of Louis Carrari. On the morning of August 7, as police worked to maintain a tenuous hold on the city, Carrari was seized from his home and beaten to death by an angry crowd. At the time of his death Carrari, himself an Italian immigrant, was married with five children.[11] His wife was later awarded $4,200 in a lawsuit against the city for his death. Totals in similar lawsuits can give us an insight into the amount of property damage resulting from the riot. Four individuals were awarded a combined total of $3,000 for various cases involving property damage, property loss, and personal injuries.[12]

The story of the murdered photographer appears to have been false as there is no mention of him in later articles on the riot. Furthermore, Carrari remained the only named victim in newspapers, lending credence to the idea that his was the only death. I was also unable to find evidence of Black Hand activity taking place in the city. Searches for the society in West Frankfort turn up no new results. However it must be noted that the city of West Frankfort does mention the society in their history of the riots. [13] Therefore, further research would be useful in determining how credible these claims are.

In December 1920 two men, Sattino DeSantis and Frank Bianca, were eventually brought to trial for the deaths of Amiel and Tony.[14] One newspaper, published after the trial’s conclusion, ventured to explain the motivation behind the murder. According to the Macomb Daily By-stander, Bianca was romantically rejected by Amiel Calcaterra’s sister. In retaliation he paid DeSantis $200 to kill the boys.[15] DeSantis, however, denied this version of events and stated that, though he did aid in the killings, Bianca was the one to cut the boys’ throats.[16] Before the trial could reach its conclusion, however, Bianca committed suicide in his jail cell on December 10.[17] DeSantis was eventually found guilty of the murders receiving the sentence of death by hanging.[18] The execution was carried out on February 11, 1921 when DeSantis was around 30 years old.[19] The execution generated a good deal of public attention with the Marion Semi-Weekly reporting that they had created an extra execution day edition of their paper which sold over 600 copies.[20]

Footnotes:

[1] “Investigate Murder of Two Young Boys,” Macomb Daily By-Stander (Macomb, IL), Aug. 6, 1920.

[2] “Mob of 3,000 to 4,000 at Carterville, ILL Take Charge of City,” Cairo Bulletin (Cairo, IL), Aug. 6, 1620.

[3] “Local Guardsmen Are Called for Riot Duty at West Frankfort,” Urbana Daily Courier (Urbana, IL), Aug. 6, 1920; “Governor Has Sent Troops to Stop Riot,” Monmouth Daily Atlas (Monmouth, IL), Aug. 6, 1920.

[4] “Rioters Control Illinois Town,” Macomb Daily By-stander (Macomb, IL), Aug. 6, 1920.

[5] “Mob of 3,000 at Carterville, Il Take Charge of City,” Cairo Bulletin (Cairo, IL), Aug. 6, 1920.

[6] “Investigate Murder of Two Young Boys,” Macomb Daily By-Stander (Macomb, IL), Aug. 6, 1920.

[7] “Local Guardsmen are Called for Riot Duty at West Frankfort,” Urbana Daily Courier (Urbana, IL), Aug. 6, 1920.

[8] “Quiet Restored in West Frankfort by State Guardsmen,” Cairo Bulletin (Cairo, IL), Aug, 7, 1920.

[9] “Quiet Restored in West Frankfort by State Guardsmen,” Cairo Bulletin (Cairo, IL), Aug 7, 1920.

[10] “Italian ‘Black Hand’ Slain” Urbana Daily Courier (Urbana, IL), Mar. 26, 2910; “Lewis’ Life Is Threatened,” Urbana Daily Courier (Urbana, IL), Aug. 19, 1910.

[11] “Riots Continue in Illinois City,” Macomb Daily By-stander (Macomb, IL), Aug. 7, 1920; “Italian is Found Slain,” Urbana Daily Courier (Urbana, IL), Aug. 7, 1920.

[12] “West Frankfort Cases Settled,” Marion Semi-Weekly Leader (Marion, IL), Oct. 28, 1921.

[13] “Riot of 1920,” City of West Frankfort, IL, accessed October 24, 2018. http://www.westfrankfort-il.com/default.asp?id=267.

[14] “Men Who Caused West Frankfort Riot on Trial,” Cairo Bulletin (Cairo, IL), Dec. 7, 1920.

[15] “Hang Instigator of West Frankfort Riot,” Macomb Daily By-stander (Macomb, IL), Feb. 11, 1921.

[16] “DeSantis, Hanged at Marion, Admits Part in Murder,” Cairo Bulletin (Cairo, IL), Feb. 12, 1921.

[17] “Bianca Suicides by Hanging Trial of DeSantis Ends,” Cairo Bulletin (Cairo, IL), Dec. 11, 1920.

[18] “DeSantis Calm as Death Sentence is Pronounced on Him,” Cairo Bulletin (Cairo, IL), Dec. 21, 1920.

[19] “Italian Who Killed Two Boys Sent to Death on Gallows at Marion, Today,” Macomb Daily By-stander (Macomb, IL), Feb. 11, 1921; “DeSantis Doomed to Ignoble Death on Scaffold Today,” Cairo Bulletin (Cairo, IL), Feb. 11, 1921.

[20] “Big Sale Reported on Execution Day Extras,) Marion Semi-Weekly Leader (Marion, IL), Feb. 18, 1921.