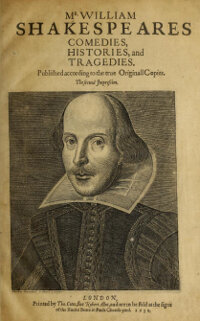

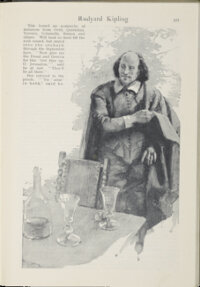

Mrs. Hoper

London: Printed for W. Owen, 1749

A member of “Shakespeare’s Ladies,” a literary club founded in 1736 to promote performances of his works, Mrs. Hoper penned her own theatre piece in which Queen Tragedy (played by Mrs. Hoper herself) languishes and cannot be revived until the ghost of Shakespeare rises to speak in the epilogue. Shakespeare’s Ladies Club supported good theatre, but, by all accounts of its two-day run, Mrs. Hoper’s play did nothing to further the cause. —VH