The IDHH is thrilled to once more partner with Analú María López, the Newberry’s Ayer Indigenous Studies Librarian, for our first post this December. Analú’s work focuses on underrepresented Indigenous narratives dealing with identity, language, and decolonization, and we are pleased to feature her writing for a second time as she sheds light on the Seeing Indian in Chicago exhibition, an outgrowth of the American Indian Oral History project highlighted in last month’s blog post.

The Chicago American Indian Photography project by Analú María López

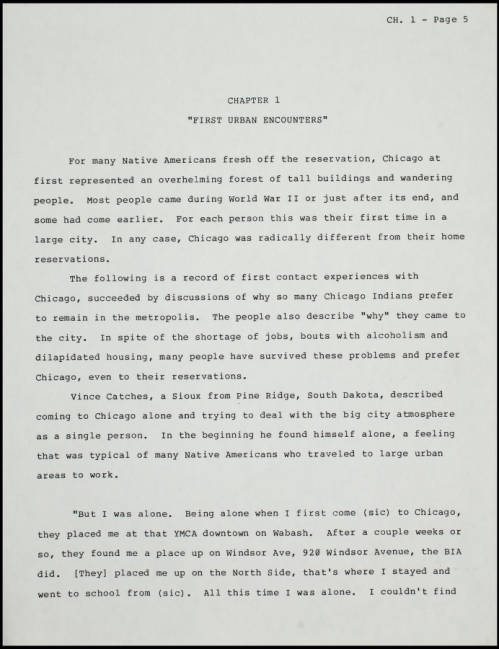

For a long time, photography has reinforced negative stereotypes of Indigenous people, oftentimes placing them in the past. When we think of “Native American” or “Indigenous photography”, we think of the cliché photographs by white photographers like Edward Curtis1, we don’t usually think of Native American or Indigenous photographers. Despite the fact that Indigenous People have long taken images of their communities, we rarely see these images uplifted or reflected in history texts, let alone in the history of photography. In fact, Indigenous Peoples embraced photography early in the nineteenth century. Some even owned and operated their own photography studios, such as the Purépecha photographer Antonio Calderón Sandoval and Tsimshian photographer Benjamin Haldane. As the photographer and educator, Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie (Seminole-Muscogee-Diné) once wrote, “No longer is the camera held by an outsider looking in, the camera is held with brown hands opening familiar worlds. We document ourselves with a humanizing eye, we create new visions with ease, and we can turn the camera and show how we see you.”

A collection of photographs titled the Chicago American Indian Photography project and Seeing Indian in Chicago exhibition records, held at the Newberry Library in Chicago, an independent research library with a focus on rare books, manuscripts, and other archival materials, highlights the Native American community in Chicago through a series of photographs created by Native and some non-Native community members. These photographs are part of the Indigenous Studies collection, which was founded on the donation from Edward E. Ayer’s Library in 1911. Ayer, a white settler, was one of the Library’s original Trustees and one of the most active collectors of his time in the field of Indigenous Americana.

An outgrowth of the American Indian Oral History project which was highlighted in last month’s blog post, included the Chicago American Indian Photography project and the subsequent Seeing Indian in Chicago exhibition, held July 22-September 21, 1985 at the Newberry Library. These projects aimed to document the Native American community in Chicago by creating an archive of photographs taken by community members over a span of 20 years. The project’s selections were chosen by an advisory group, and while Indigenous women photographers made the final list, the advisory committee’s decisions may have been based on how long the photographers had been photographing in the community.

Men’s Fancy dancer at 1982 AIC at Navy Pier, 1982. 1982. Photographed by Joe Kazumura. The Newberry Library. Chicago and the Midwest. Courtesy of The Newberry Library.

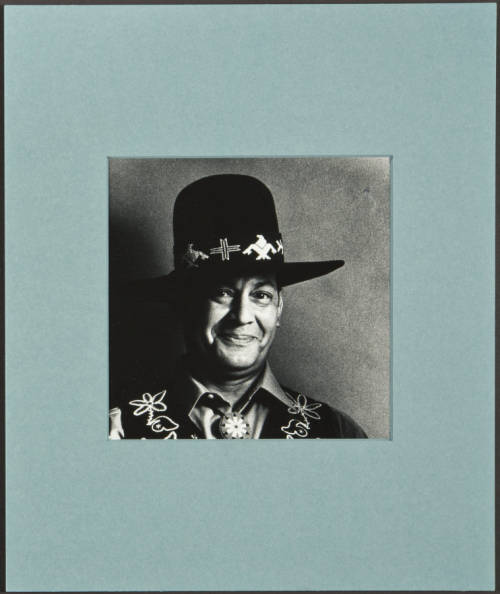

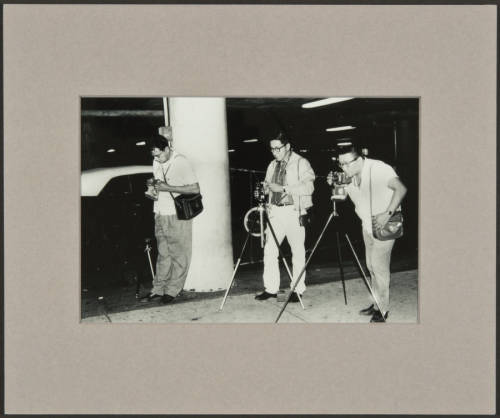

The final exhibition included six photographers of the Chicago Native American community: Dan Battise (Alabama-Coushatta), Ben Bearskin (Ho-Chunk), Orlando Cabanban (Filipino-American), Joe Kazumura (Japanese-American), F. Peter Weil, and Leroy Wesaw (Pokagon Band of Potawatomi).

At two community meetings and dinners, held at the American Indian center on May 22, 1985, audiences were shown the photographs taken by each of the photographers; three photographers were featured at each meeting. Many identifications of the individuals in the photographs were made during the viewing of the photographs. On July 26, 1985, an opening was planned to commemorate the start of the exhibition, and attempts were made to make it a community event. A neighborhood spiritual leader conducted a prayer, then dancers and singers performed. At least half of the 400 persons who attended the brief event were members of the Chicago Native American community.

Images of the photographers, Powwow celebrations, community events and clubs such as the Camera and Canoe Club are just a few images seen within this collection. The Camera Club, first founded in the 1960s, often met at the American Indian Center in Chicago twice a week on Thursdays and Saturdays. At one point, the Camera Club proposed building a traditional black and white darkroom where youth could learn how to print from negatives.

Despite some obstacles, such as timeline and prohibitive printing costs, the Chicago American Indian Photography project’s overall success, which led to the organization of the Seeing Indian in Chicago exhibition, reflects a growing consciousness among Chicago’s Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities that Indigenous histories must continue to be told and uplifted through the lens of the community.

References:

1Edward Sheriff Curtis was an American photographer and ethnologist whose work focused on the American West and on Native American people. Curtis’ portraits reinforced the Vanishing Race myth: often, and problematically photographing Native people as ethnographic depictions of a “disappearing” people. The “Vanishing Race” myth derived its name from the caption of Edward Curtis’s photograph of Diné riders disappearing into the distance.

Want to see more?

Browse the full Edward E. Ayer Digital Collection from The Newberry Library as well as additional items connected to the Seeing Indian in Chicago exhibition on the IDHH.

Visit the IDHH to discover even more items related to Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

Visit The Newberry’s website for additional information about American Indian and Indigenous Studies at The Newberry.