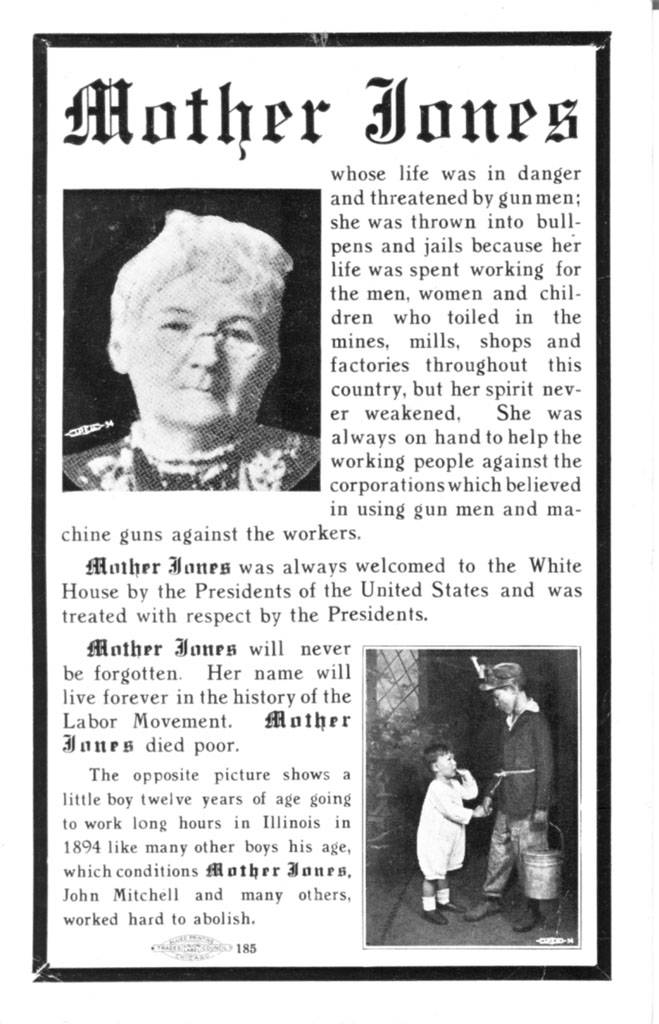

Mother Jones is one of the most recognizable figures in the labor struggle of the 19th and 20th centuries. Dressed in all black, wearing outdated dresses and speaking with a thick Irish brogue, Mary Harris “Mother” Jones is known as a fierce union and workers’ rights organizer. In The American Songbag, Carl Sandburg suggests that the folk song “She’ll be Coming ‘Round the Mountain” is based on Mother Jones’ labor organizing around the mines of West Virginia. Her imprisonment in a 1913 labor strike is celebrated by a West Virginian Historic Highway marker: “PRATT. First Settled in the early 1780’s…Labor organizer ‘Mother Jones spent her 84th birthday imprisoned here.” It’s been 89 years since her passing on November 30th, 1930. Although we’re a few weeks late, we wanted to commemorate her passing as an occasion to discuss the Mount Olive Monument and connection to the Virden Massacre.

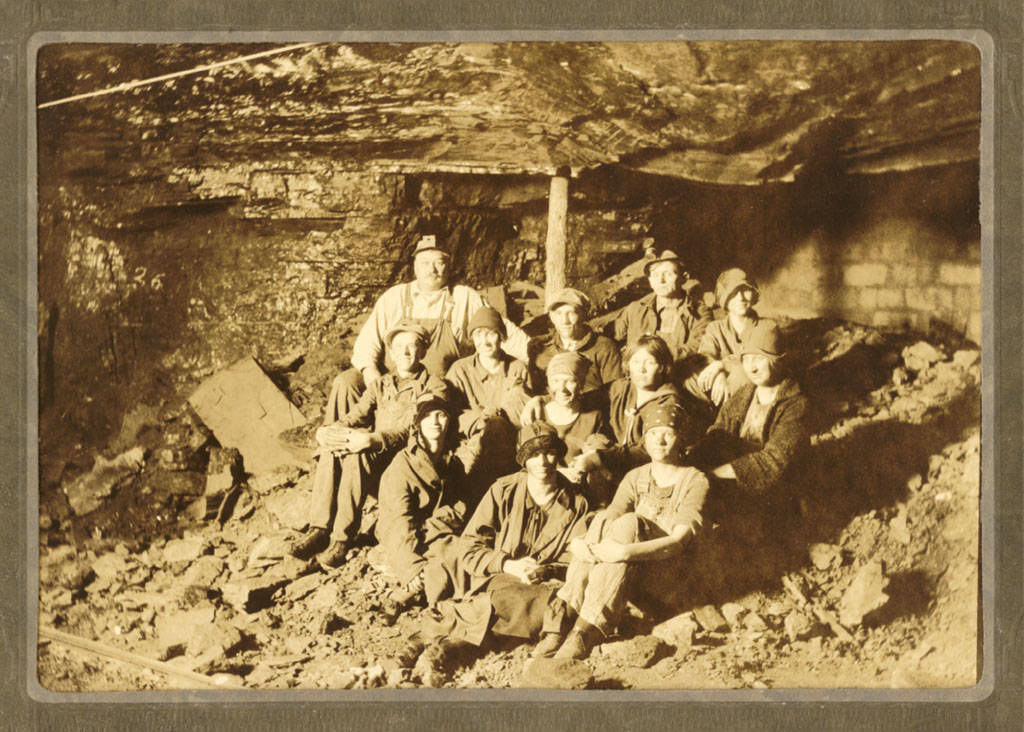

But how did she become to be buried in a small town, alongside a memorial for an event she was not present for, but claimed the lives of seven miners? Mount Olive Public Library’s collection, “Mining and Mother Jones in Mount Olive” contains images of mining in Mount Olive and the story of how one of America’s most famous labor organizers and leaders was buried in a small town in Southern Illinois.

Coal and mining has a long history in Illinois- Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet observed coal along the banks of the Illinois River. In the early 19th century, attracted to farming opportunities, anglo-americans began their migration to Illinois from Appalachia and then from around the world, and started using coal as fuel. By 1818 coal production was taking place along the banks of the Big Muddy River as coal outcropping from river banks was easily harvested.

Coal mines were, and still are, the economic powerhouse for many communities across Illinois, and so prominent that towns were named after the fuel, like Carbondale and Coal City, and Diamond (named after “black diamonds”). A coal boom in the 1860’s rocked the relatively small mines that had been powering Illinois and other parts of the Americas for the past 50 years. It coincided with the expansion of railroads across the state, connecting the most-rural parts of Illinois to growing metropolises urgently in need of coal, and moving further into a fully industrialized economy.

The first small unions were reported in 1861, but were short-lived, and often overpowered by the first monoliths of coal mining. Poor working conditions in mines, working seven days a week for low pay balancing the physical cost of labor in the mines prompted unions to begin to form with more vigor. The labor movement, with its epicenter in Chicago, radiated along the railroad lines being built across the nation, carrying union values to places like Virden, and news about the working conditions and hardships to organizers like Mother Jones. By the 1880’s workers’ rights was a national conversation. Federations of unions were forming creating the linkages between the full economy, and strengthening the human ties across class in a country in the adolescence of its industrialization.

Mary Harris “Mother” Jones lost her dress shop in the Chicago Fire of 1871. The city’s rapid rebuilding brought a new intensity to the politics of a city that was already economically stratified and growing rapidly through industrialization. The Knights of Labor, an industrial union open to all workers held meetings that Mother Jones’ attended and became radicalized through. The Knights of Labor had become popular with Pennsylvania coal miners in the 1870’s and shared a close friendship with Miners and Mine Laborers Benevolent Protective Association. Together, the two organized wildcat strikes across industry lines, demanding an eight hour workday, better pay, and working conditions. After the Haymarket Riots of 1890, the two unions merged into the United Miners Association. Deeply empathetic to the struggles of coal miners and their families, including the harsh conditions in the mine, and the virtual indentured servitude of being forced to live in high-cost company housing and shop in high-cost company stores on low company pay, Mother Jones made the rights of miners and their families her champion cause.

In 1898, the Virden-Chicago Coal Company was the largest coal producer in the state. An Illinois-wide strike had led to negotiations between representatives of the Company and union representatives. However, worried that the agreement would raise the costs of the coal so high that it would make their coal unable to compete with other companies’ coal on the Chicago market, the Virden-Chicago company made arrangements to bring in 50 non-union African-American miners from Alabama, advertising rates of 30¢ per ton of coal.

Strikebreaking with African American workers certainly stoked racial tensions in Southern Illinois and the Labor Movement, a region that was still struggling with racism, poverty, and the fall-out of the civil war. The southern third of the state was surrounded by slave holding states and created a crucible for racial tensions as it intersected with poverty. The United Mine Workers itself was racially integrated and included chapters in Alabama of African American miners who had warned against strikebreaking in Illinois. Written into the initial constitution of the UMW was the inclusion of all people, under the principle and theory that for there to be power in the union, the number of members had to rise. Mining remained one of the few jobs available to African Americans in the Southern Appalachian states including those in North East Alabama. UWM’s inclusion, met both needs. Virden-Chicago Coal Company’s decision to advertise to and employ non-union miners, was an active decision to skirt the union and negotiations made that summer, and in doing so, capitalize on the racism and racial violence. It exploited a promise of a better life for African Americans, while also creating a deeper and more entangled conflict between the white dominated labor unions and African Americans.

The union struck the mine at Virden, furious that their concessions had not been met. On October 12th 1898, a train with the Alabaman strikebreakers arrived at Virden. Beside the would-be miners, were guards armed with rifles, sent to protect the Alabamans from the miners at Virden, who they knew would be armed. Frank W. Lukens, a manager for the Virden-Chicago Coal Company requested that Governor Tanner send in the National Guard to ensure that the strike breakers would have safe entry to the mine, but was refused.

As the train pulled into the minehead’s tracks, the union surrounded the train and the guards inside opened fire. The massacre–as it was described later– only lasted 10 minutes and left seven miners dead and 30 more wounded. 4 guards were also killed, and an unreported number of Alabaman workers wounded. The train pulled out and retreated for Springfield. The entire day, the stakes were incredibly high and incredibly clear to all involved except the strike breakers, who were kept in the dark of the strike and the mounting violence in strike breaking. Riots continued for the rest of the day.

Seven dead miners first buried in the Mt. Olive cemetery, some 45 miles away from Virden and the site of the massacre- but after the original donor of the land objected to the Union demonstrations commemorating their death, the union began to fund raise for its own acre of burial space. It is the only union owned cemetery in the nation.

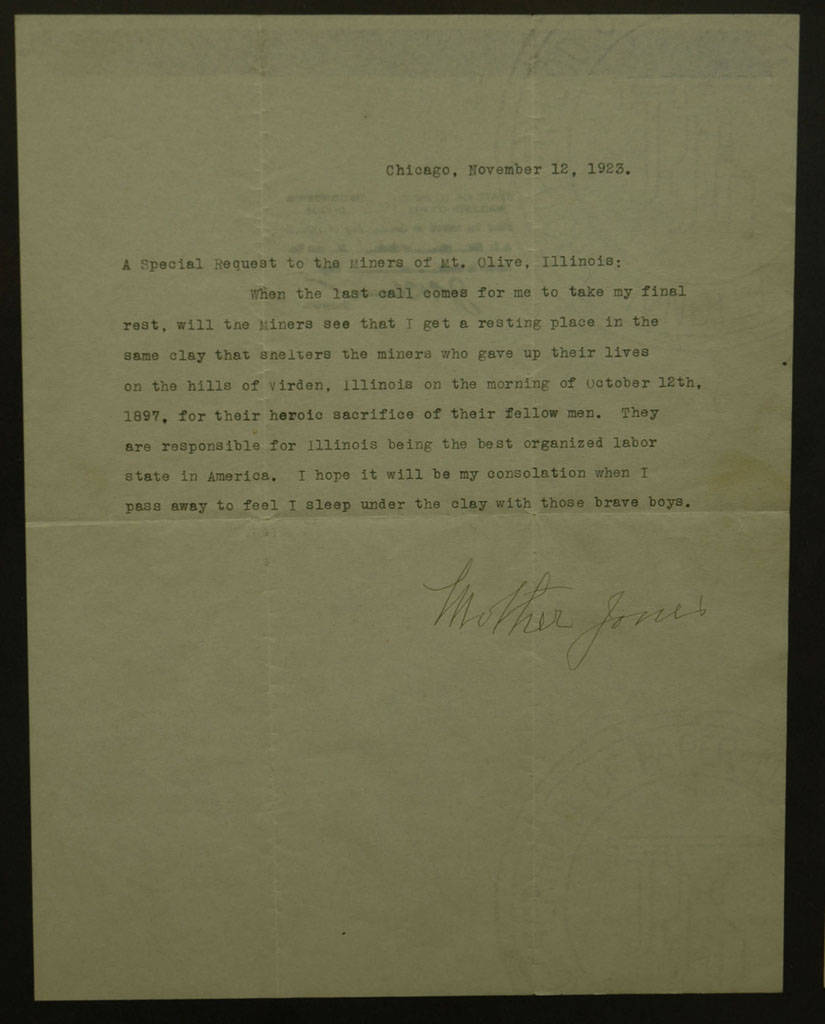

Mother Jones was not at the picket line during the Virden Massacre. But after speaking at the cemetery in October 1923, in memorial of the massacre, wrote to the miners asking that they allow her to be buried alongside the miners who gave up their lives in the massacre.

A large part of Mother Jones’ organizing took place in West Virginia throughout the chaotic Coal Wars between 1912 and 1930. Virden preceded them, but ushered in a strong unionism that extended across the rural midlands of the United States east of the Mississippi. Today, a monument that celebrates her life and the lives of miners stands at the cemetery.

For more on Mother Jones and Mount Olive visit the IDHH.