We would like to begin today by recognizing and acknowledging that the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign is on the lands of the Peoria, Kaskaskia, Piankashaw, Wea, Miami, Mascoutin, Odawa, Sauk, Mesquaki, Kickapoo, Potawatomi, Ojibwe, and Chickasaw Nations. These lands were the traditional territory of these Native Nations prior to their forced removal; these lands continue to carry the stories of these Nations and their struggles for survival and identity.

As a land-grant institution, the University of Illinois has a particular responsibility to acknowledge the peoples of these lands, as well as the histories of dispossession that have allowed for the growth of this institution for the past 150 years. We are also obligated to reflect on and actively address these histories and the role that this university has played in shaping them.

Located near the confluence of several waterways, the Newberry Library sits on land that intersects with the aboriginal homelands of several tribal nations: the Council of the Three Fires: the Potawatomi, Odawa, and Ojibwe Nations; the Illinois Confederacy: the Peoria and Kaskaskia Nations; and the Myaamia, Wea, Thakiwaki, and Meskwaki Nations. The Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Kiikaapoi, and Mascouten Nations also call the region of northeast Illinois home. Indigenous people continue to live in this area and celebrate their traditional teachings and lifeways. Today, Chicago is home to one of the largest urban Indigenous communities in the United States, and this land remains an important place for Indigenous peoples. As a Chicago institution, it is the Newberry’s responsibility to acknowledge this historical context and build reciprocal relationships with the tribal nations on whose lands we are situated.

The IDHH contains some content that may be harmful or difficult to view. Our cultural heritage partners collect materials from history, as well as artifacts from many cultures and time periods, to preserve and make available the historical record. Please view the Digital Public Library of America’s (DPLA) Statement on Potentially Harmful Content for further information.

With the month coming to a close, the IDHH dedicates this post to Indigenous voices, highlighting November as National Native American Heritage Month. The earliest calls for a day to officially recognize and commemorate the cultures and contributions of Indigenous peoples occurred in 1915 at the annual Congress of the American Indian Association in Lawrence, Kansas. Over the course of a century, various states passed legislation declaring American Indian Day on different dates throughout the year, and national legislation and proclamations were also passed celebrating a Native American Awareness Week or American Indian Week. However, it was not until 1990, when George H. W. Bush declared November as National American Indian Heritage Month, that the United States officially committed a month to recognizing and commemorating the cultures and contributions of Indigenous peoples.

The IDHH is thrilled to partner with Analú María López, Ayer Indigenous Studies Librarian at the Newberry, in the creation of this post and to benefit from her subject expertise. Analú’s work focuses on underrepresented Indigenous narratives dealing with identity, language, and decolonization, and she has chosen to feature a one-of-a-kind item from the Newberry’s collections which centers Indigenous peoples: the unpublished manuscript Native Voices in the City.

Native Voices in Zhekagoynak, Zhigaagoong, Šikaakonki by Analú María López

Zhekagoynak, Zhigaagoong, and Šikaakonki (“Chicago” in Potawatomi, Ojibwe, and Myaamia respectively), has always been and will always be Indigenous land. Since time immemorial Indigenous people have lived on and stewarded this land we now call “Chicago.” Although Indigenous people were forcibly removed from the city of Chicago through a series of treaties,1 and in spite of settler-colonial projects seeking to remove Indigenous people from the city, Indigenous people have not vanished or ceded their relationships to Chicago. Today, Chicago is home to one of the largest urban Indigenous population in the United States, with more than 65,000 Native Americans in the greater metropolitan area and some 175 different tribes represented.2 And yet, settlers have often frozen Native Americans in the United States and specifically in the city of “Chicago” to the distant past, usually using settler narratives and not Indigenous histories, contributions and stories.

A collection of interviews held at the Newberry Library in Chicago, an independent research library with a focus on rare books, manuscripts, and other archival materials, highlights Native American urban experiences in “Chicago” through the vehicle of oral history. These interviews are part of the Indigenous Studies collection, which was founded on the donation from Edward E. Ayer’s Library in 1911. Ayer, a white settler, was one of the Library’s original Trustees and one of the most active collectors of his time in the field of Indigenous Americana.

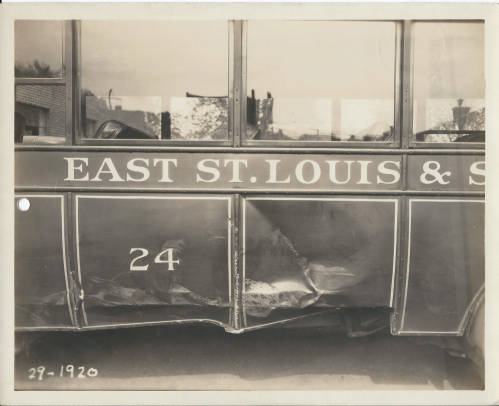

Native voices in the city. Page 5. 1982-1985. Newberry Library. Edward E. Ayer Digital Collection. Courtesy of The Newberry Library.

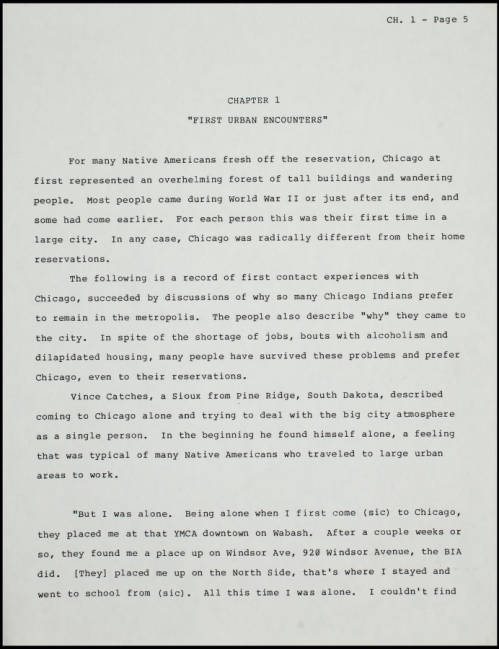

Native voices in the city. Page 16. 1982-1985. Newberry Library. Edward E. Ayer Digital Collection. Courtesy of The Newberry Library.

In 1982 the D’Arcy McNickle Center for American Indian and Indigenous Studies (then called the D’Arcy McNickle Center for the History of the American Indian) submitted a proposal to the Illinois Humanities Council to initiate a collaborative oral history project with members of the Chicago Native American community. The resulting, “Chicago American Indian Oral History Project,” operated between 1982 and 1984. The interviews were first captured on reel-to-reel and cassette tape recordings; they were later transcribed. The project interviewers and organizers3 gathered the memories of twenty-three Chicago Native American residents over the course of two years. The persons interviewed reflected the diversity of the Chicago Native American community, with individuals primarily from the northern and central Great Plains, as well as the western Great Lakes. The transcripts were then combined into an unpublished typescript titled “Native Voices in the City,” incorporating excerpts from the original interviews.

Although many community members and Newberry staff were involved in the project, Dorene Wiese (White Earth Band of Ojibwe) of Truman College played an instrumental role in the directing of the oral history project –

“The excitement of having our Native community college students both interview and be interviewed for the project. It was a lifelong dream of mine to document the history of our Native people living in Chicago because oral history projects can help place us [Native people] and our ancestors in time capsules of National Policy and truth, without being tied to just dates and names which mean little to Native students. Oral history for Native people makes it personal and exciting, and lays the foundation for understanding history in the United States.”

-Dorene Wiese (White Earth Band of Ojibwe)

This project intended to document Native American relocation to the city of Chicago with perspectives from individuals who came to the city during the Relocation era of the 1950s.4 The project also aimed to tape and transcribe the interviews with elders who best remembered all the stages of the evolution of the community, in hopes that the project would continue and to create a wider awareness of the history of Native American people in Chicago. An advisory board composed mainly of Chicago Native American people oversaw the project; it trained and utilized Chicago Native American community members as interviewers; and it held three public forums to publicize and promote the documentation project.

While relocation to the city offered opportunities to some individuals, many Native American families found it difficult to relocate to the city, and this had a direct impact on the demographics of the Native population in Chicago: “The experience for Native American people who came to Chicago can easily be divided into two groups: those who experienced the city and decided to return home and those who decided to stay. The latter are the people who make up the population of approximately 13,000 in Chicago” (p. 16, Native Voices in the City). The relocation program was frequently chastised for making hollow promises, as evidenced by the manuscript’s numerous first-person accounts. Housing insecurity, food apartheid within neighborhoods, and a lack of opportunities for the Native American community in Chicago, still problems in the city to this day, can be traced back to the 1950s government colonial efforts designed to drive Native Americans to assimilate into dominant white society.

References:

1The Chicago area was directly affected by five of the approximately 370 ratified treaties between the federal government and Native American nations signed from 1778 to 1871. Native American treaty making ended by law in 1871, but an additional 73 “agreements” containing similar provisions were ratified up to 1911. Treaties involving the Chicago area were signed in 1795, 1816, 1821, 1829, and 1833. From the Encyclopedia of Chicago

2Native American Chicagoans Report, Institute for Research on Race and Public Policy, University of Illinois, 2019

3For a complete listing of project interviewers and organizers, go to the Chicago American Indian Oral History Project finding aid

4Read more about this colonial project: Uprooted: The 1950s Plan to Erase Indian Country

The IDHH would again like to thank Analú María López for sharing her expertise and insight this National Native American Heritage Month into the unique item that is the unpublished Native Voices in the City manuscript. We are grateful for the opportunity to collaborate with her on this post, and look forward to featuring Analú’s work next month with a related post about the 1985 Seeing Indian in Chicago exhibition. Stay tuned for that post in the coming weeks, and enjoy a teaser image from the digital collection “Seeing Indian in Chicago Exhibition Records” below!

Women dancers line up for Grand Entry at the Chicago Conference Pow Wow held at field house of the University of Chicago, 1961. 1961. Photographed by Peter F. Weil. Newberry Library. Chicago and the Midwest. Courtesy of The Newberry Library.

Want to see more?

Browse the full Edward E. Ayer Digital Collection from The Newberry Library and the entire Native Voices in the City manuscript on the IDHH.

Visit the IDHH to discover even more items related to Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

Visit The Newberry’s website for additional information about the crafting of their Land Acknowledgement Statement and about American Indian and Indigenous Studies at The Newberry.