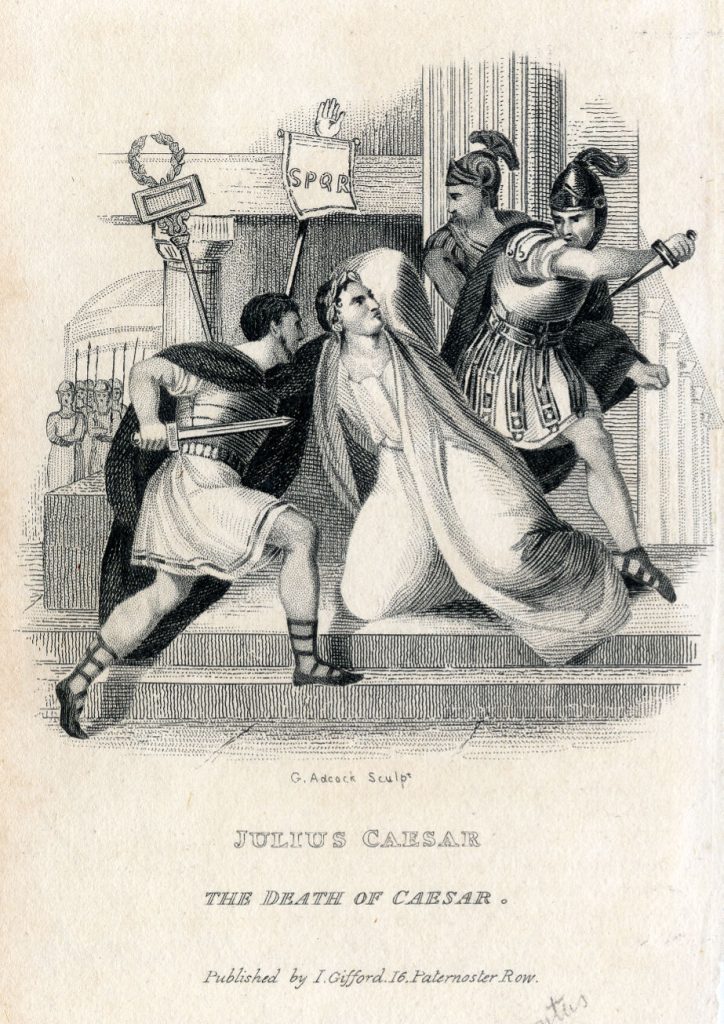

For the ancient Romans, the Ides functioned as one of three fixed points occurring each month that helped them keep track of the current date in the Roman calendar. The Ides landed around the 13th day in most months, but took place on the 15th day in a few months of the year such as March. The Ides of March is particularly infamous due to its association with the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE by Roman senators. Marking the end of the Roman Republic, Caesar’s downfall during the Ides of March would be chronicled by Greek-Roman writer Plutarch in his work Parallel Lives, eventually inspiring a number of adaptations and artworks over the centuries depicting this historical event.

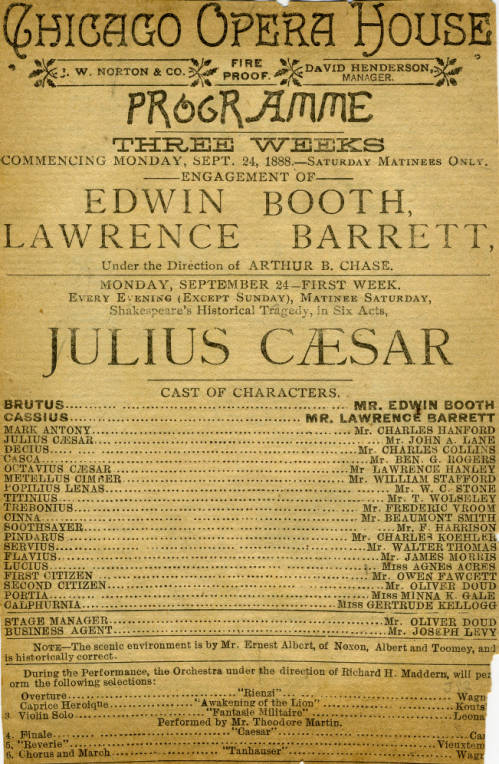

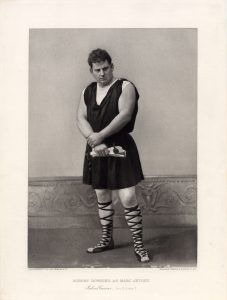

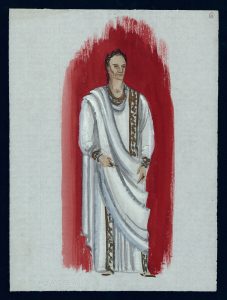

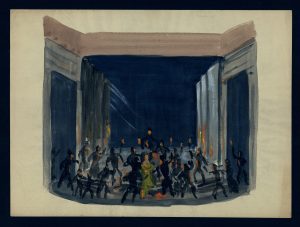

One of the more well-known adaptations of Plutarch’s writing on Julius Caesar is William Shakespeare’s play Julius Caesar. First produced in 1599, perhaps for the opening of the Globe Theatre that same year, Shakespeare dramatizes the events surrounding Caesar’s assassination to pose questions about authority, political power, and fate. The tragedy play has had a varied production history over the last 423 years, as political regimes and movements have found the work’s themes sympathetic or contrary to their cause. Illinois theatres have hosted a number of historic productions of the piece, including a three-week run in 1888 at the Chicago Opera House featuring in the lead role of Brutus the actor Edwin Booth, brother of actor John Wilkes Booth infamous for assassinating Abraham Lincoln in 1865. Though during his attack John Wilkes Booth credits himself as shouting “Sic semper tyrannis!” — a phrase which his brother Edwin would cry in his role as Brutus — it is the words the soothsayer character uses to warn Caesar that we repeat today: “Beware the Ides of March.”

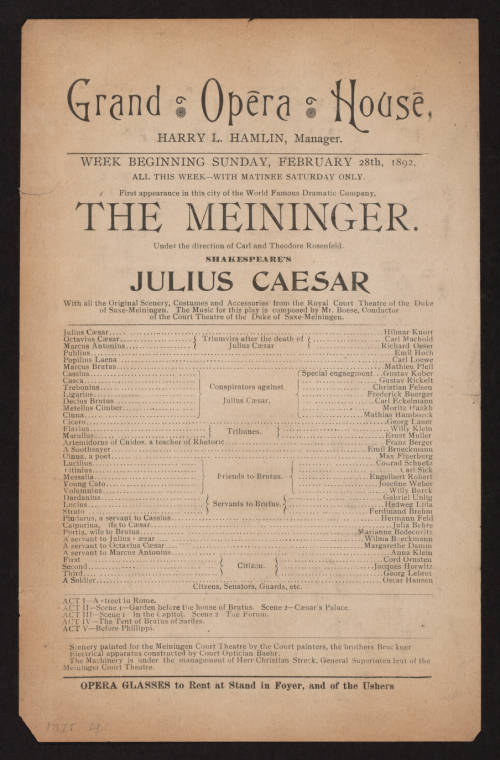

Below are a few of our favorite items featuring Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar:

Want to see more?

Visit the IDHH to view even more items related to Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar.