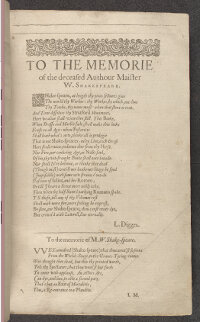

J. M.

In Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, histories & tragedies, published according to the true originall copies.

London: Printed by Tho. Cotes, for Robert Allot, and are to be fold [sic] at the signe of the Blacke Beare in Pauls Church-yard, 1632

One of five prefatory poems in the First Folio, this panegyric speaks directly to Shakespeare as an actor who has stepped off the stage for a costume change. J. M. is probably James Mabbe (1571–1642?), a scholar, translator, and minor literary figure from Oxford. His charming poem laments the loss of Shakespeare and plays upon his acting career, equating death with being offstage and this printed collection with an encore performance. —VH