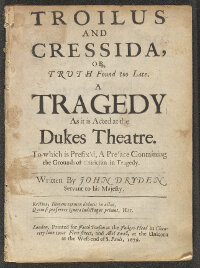

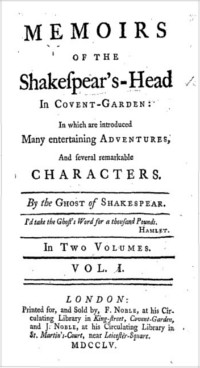

John Dryden

London: Printed for Jacob Tonson at the Judges-Head in Chancery-lane near Fleet-street, and Abel Swall, at the Unicorn at the Wes-end of S. Pauls, 1679

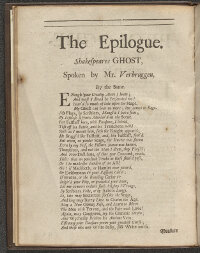

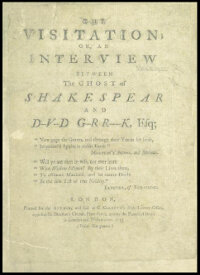

Acclaimed contemporary actor Thomas Betterton appears on-stage and delivers a prologue of 40-lines introducing himself as the “awfull ghost” of William Shakespeare. In the long prose preface to the adaptation, Dryden compares Shakespeare to Aeschylus for “noble boldness of expression,” “lofty and heroick,” “daring to extravagance.” He is a “more Masculine, a bolder and more fiery Genius” than Fletcher. Likewise, then, in the prologue, Shakespeare the Ghost introduces his play as “rough-drawn” but full of “Master-strokes,” “manly” and “bold.” He describes himself as “untaught,” “untutored,” creating theatre in England out of his own “abundance” in the midst of a “barbarous Age.” Like “fruitfull Britain,” he is “rich without supply,” i.e. without importing any “store” from abroad. He decries the feebleness of his successors in the present age and says that their “insipid stuff” would be more fitting to a “Judge or Alderman”: “dullness is decent in the Church and State.” —PG